Stanley Johnson and his spectacular outfits are greatly loved on Well Street, Hackney, where I met him, and where he’s often to be seen at veggie café The Grand Howl and musical emporium Kristina Records. After a few chats, Stanley gave me permission to come round and talk to him in more depth, and to bring a photographer, Margaret Marks, tireless chronicler of the sordid underbelly of Upminster. This is but a preliminary report.

Stanley Kenneth Johnson was born on March 14th 1937 in the Bethnal Green Hospital at 214 Cambridge Heath Road, of which only the admin block has survived Adolf Hitler and the planners and developers.1The Bethnal Green Infirmary, later Hospital, was the birthplace of a host of half-forgotten names, including, in 1946, Helen Shapiro, also of Eastern European Jewish stock, who grew up in Clapton and Victoria Park:

He is not Boris Johnson’s father, but a portrait of the Prime Minister is one of a multitude adorning his kitchen walls, and the two correspond. A war toddler, he lived opposite the glorious 1872 Wesleyan Methodist Chapel which stood on the corner of Queen Anne Road and Cassland Road until its destruction by a high explosive bomb in October 1940. He recalls the network of air-raid shelters on the Cassland Road side of Well Street Common,2An aside. Well Street Common extended to Well Street before 19th century development of the area, and J.J. Sexby’s The municipal parks, gardens, and open spaces of London (1898) says that Well Street’s well was at Cottage Place, which Stanford’s library map of London and its suburbs (1872) shows at the junction of Well Street with Stebbing Place (Cassland Road) and Grove Street/Park Terrace (Lauriston Road):

This has been bothering me for ages.

in which children played after the war, and which are still apparent in the form of minor subsidence. One night he stood outside the shelters, waving to the bombers, had to be dragged downstairs, and was subsequently evacuated to Newcastle upon Tyne. His drumming career was to take him to Germany, but he was too polite to exact musical revenge.

Stanley started playing drums “off his own bat” when he was about 15. “There used to be a shop in the West End, and they used to have drums downstairs, and we used to go and bang on them.” I believe that this was when he was working as Junior Messenger at the American embassy in Grosvenor Square, where he acquired his lifelong love of distinctive clothes and Americana. At this stage he also used to frequent a magic shop, probably Davenports at 25 New Oxford Street, where he used to bump into Tommy Cooper (just like that!) on Saturday mornings. A member then of the Institute of Magicians and currently of IBM (the International Brotherhood of Magicians), Stanley worked for a while as a magician, achieving a proficiency with his gag props that always eluded Tommy.3Both Tommy and Stanley specialised in the rope trick, but only Tommy’s is on film:

He carried on playing drums for party nights during his three years National Service as an Air Traffic Control Operations Clerk in the RAF, an interlude which goes some way to explaining the signed photos from the Red Arrows on his wall.

Work followed at venues including the Van Gogh Bar, a notorious drinking den upstairs at the Latin Quarter night club and restaurant at 13-17 Wardour Street, Soho, as well as a summer season with an organist at a Pontins holiday camp in Devon. A musician’s life is rarely a simple one, and other work in this period included a spell selling gherkins, pickled onions and other preserves from a stall opposite the cinema at Walthamstow market.

By this time he had acquired his lifelong passion for rock ‘n’ roll, and had among others seen Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran sharing a bill at the Finsbury Park Empire as well as Frankie Laine at the London Palladium.

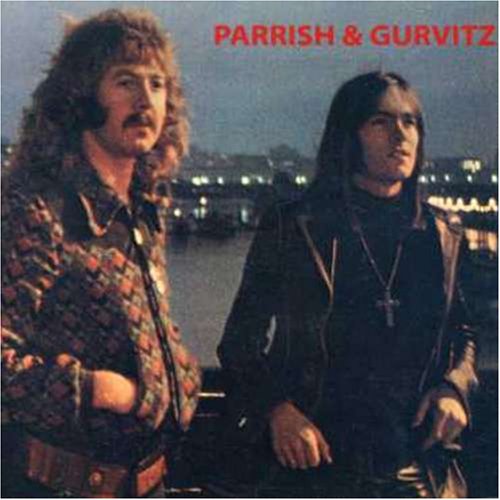

Stanley turned pro in 1962. In 1963 he was approached by The Londoners, a band invented shortly before in the Paul Anthony Hair Salon in Ilford, Essex, when proprietor Paul Gurvitz (aka Curtis, guitar) discovered that he shared a passion for both popular music and pompadours with customer Brian Morris (aka Parrish, guitar and vocals). Unfortunately I have no closeups from the era, and by 1971 Brian and Paul (aka Parrish and Gurvitz) had progressed to what I think of as the proto-mullet and -grebo:

The Londoners were a four-piece (Mick Palmer played bass), but the key figure was Paul’s father, Sam Gurvitz, who I assume came from a Jewish family from the western fringes of the Russian Empire. Sam had been working as road manager for Cliff Richard’s Shadows, and used his influence to book his son’s band, with Stanley on drums, to play rock and roll covers for six months each on US army bases in France and Germany. Brian Parrish:

The black guys liked us best. We had no idea why they, in particular, took us to heart, but it could be because we were playing their music – rhythm ‘n’ blues – probably quite badly, but with great enthusiasm! … We saw nothing incongruous about four white English boys playing Parchman Farm, a song about a Louisiana jail famous for its harsh treatment of black prisoners.4Mose Allison’s 1957 recording of Bukka White’s Parchman Farm was popular with early British blues figures like John Mayall. Here’s Mose singing “I ain’t never done no man no harm … all I did was shoot my wife”:

We knew nothing!

But Sam also worked as road manager for the American rock and roll and rockabilly legend, Gene Vincent (1935-1971), who had been singing Be-Bop-A-Lula and shaking his shattered left leg for British audiences since 1959, when he had fled from the American tax authorities and the Musicians’ Union after selling his American band’s equipment to pay not quite enough of a tax bill. In London the TV pop impresario Jack Good transformed him, says Richard Williams:

[He] concluded immediately that the singer’s homespun lumberjack shirt and blue jeans failed to reflect the latent menace of the man who intoned Be Bop A Lula with a sinister hiccup. Good re-envisioned Vincent as a rock’n’roll version of Laurence Olivier’s Richard III, putting him in black leather from head to toe, including gloves, to go with the iron caliper that he wore on one leg as the result of a motorcycle accident. When Vincent performed on stage, Good stood in the wings and was heard to encourage the singer to accentuate his wounded vulnerability with cries of “Limp, you bugger, limp!”

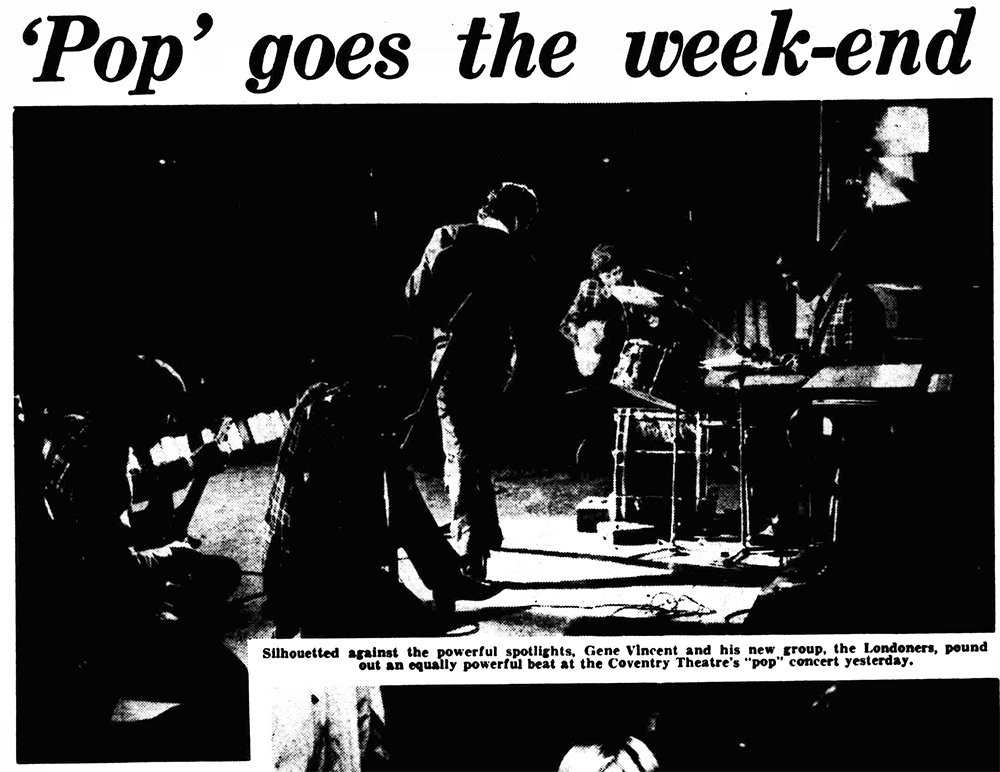

In 1960 Gene’s leg may have been further damaged in the taxi crash in Chippenham which killed fellow rock ‘n’ roll star Eddie Cochran, of whom he said, “Eddie and I were as close as two guys can get without being queer.” By 1963 Gene’s act looked like this:

In 1964, when The Londoners recrossed the Channel, Gene was struggling in the face of the British musical renaissance protagonised by the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. He wanted a new backing band to replace The Shouts from Liverpool, and Sam arranged for The Londoners to audition for him in a West End pub. On finishing, Gene said, to their considerable surprise, “We start rehearsing tomorrow,” and after a few days they went on tour, playing for six weeks in theatres all over the country, from the Newcastle Odeon to the Cardiff Odeon, with many an Odeon in between.5Tour dates here. I guess we’re talking post-October 10th.

“Silhouetted against the powerful spotlights, Gene Vincent and his new band, the Londoners, pound out an equally powerful beat at the Coventry Theatre’s ‘pop’ concert yesterday.” (Coventry Evening Telegraph, Monday 19 October 1964)

“Silhouetted against the powerful spotlights, Gene Vincent and his new band, the Londoners, pound out an equally powerful beat at the Coventry Theatre’s ‘pop’ concert yesterday.” (Coventry Evening Telegraph, Monday 19 October 1964)

Gene was already majoring in the alcohol and painkillers that were to give him his fatal ulcer, but Stanley recalls getting on well with him, “though he didn’t stand fools gladly,” while Brian says he learned two lessons:

One: Heroes are human beings. Two: Playing rock music is the best job in the world.

Gene Vincent with The Londoners at London University’s Glad Rag Ball at the Empire Pool, Wembley, 20th November 1964. With permission from VoxAC100.

At least part of this tour was as a component of the immaculately packaged Big Beat Show, promoted by the first manager to employ a stable of artists rather than simply taking a percentage: Larry Parnes (another Jewish surname once found in the territories between Austria and Russia), known in the trade as Parnes, Shillings and Pence.6Here is a slightly truncated version of the documentary about Larry Parnes, entitled Mr Parnes, Shillings and Pence:

Here’s a typical programme, from a show in Bradford:

… and here follows a YouTube playlist of more or less relevant numbers by the bands:

- The Londoners: “Bring it on home to me”, recorded after Stanley left

- The Puppets (Joe Meek): “Baby don’t cry”

- The Beat Merchants: “Pretty face”

- Daryl Quist (who had been a dancer in Tommy Steele’s panto, Humpty Dumpty): “Above and beyond”

- Gene Vincent: “Long tall Sally”, with another band

- The Applejacks: “Tell me when”

- Lulu & The Luvvers: “Shout”

- Millie Small: “My boy lollipop”, with a classy sax solo instead of the bloody harmonica on the original

- The Honeycombs (also originally a band of hairdressers): “Have I the right to hold you?”

After the six week tour, The Londoners were contracted by the Star Club to play at their venues in Bremen and Hamburg, but Stanley stayed in London. There is talk of a partnership with Gene after the tour, and of contacts until the end, on which I will report after the Plague has passed. He worked as a drummer with various groups until he hung up his sticks in 1972 and got a “proper” job.

On reflection, I can’t help thinking how fortunate Stanley has been in comparison to his musical hero. On the one hand, Gene in his later years was cherished for who he had been 15 years earlier, and in spite of the difficult person he had become. On the other, Stanley is cherished for who he is now – for his get-ups and charm – and, despite the fanclub, many younger people don’t know who Gene Vincent was, or don’t know enough about him to be able to appreciate Stanley’s connection. This musically knowledgeable gent thought I meant Gene Pitney, and some haven’t even heard of Ian Dury, sweet Gene Vincent‘s greatest fan:

If both of us survive Corvid-19, then I plan to find out more about Stanley’s new band; follow up connections to Paul McCartney and Clint Eastwood; accompany him to his favourite boutique in Kingsland Shopping Centre (which Phoebe Luckhurst also thinks is the most exciting place in London); and photograph him in some of his numerous exotic outfits. But here, for now, is a lovely portrait of Stanley Johnson by Margaret Marks, with, in the background, his mum on her wedding day:

Update, early 2021

Brian Whar has posted some superb photos of Stanley on his website and his Instagram account.

Here are recordings of Stanley and The Zimmermen rehearsing at Gun Factory Studio, Hackney:

Update, 22 April 2022

Stanley was hit by a local driver while crossing the zebra at the Kenton Arms on 24 November 2021 and died on 17 April 2022. Here’s a great short by Brian Whar, who has worked incredibly hard for Stanley over the past months and years:

And here’s the crowdfunder for Stan’s funeral.

Anecnotes

- 1The Bethnal Green Infirmary, later Hospital, was the birthplace of a host of half-forgotten names, including, in 1946, Helen Shapiro, also of Eastern European Jewish stock, who grew up in Clapton and Victoria Park:

- 2An aside. Well Street Common extended to Well Street before 19th century development of the area, and J.J. Sexby’s The municipal parks, gardens, and open spaces of London (1898) says that Well Street’s well was at Cottage Place, which Stanford’s library map of London and its suburbs (1872) shows at the junction of Well Street with Stebbing Place (Cassland Road) and Grove Street/Park Terrace (Lauriston Road):

This has been bothering me for ages. - 3Both Tommy and Stanley specialised in the rope trick, but only Tommy’s is on film:

- 4Mose Allison’s 1957 recording of Bukka White’s Parchman Farm was popular with early British blues figures like John Mayall. Here’s Mose singing “I ain’t never done no man no harm … all I did was shoot my wife”:

- 5Tour dates here. I guess we’re talking post-October 10th.

- 6Here is a slightly truncated version of the documentary about Larry Parnes, entitled Mr Parnes, Shillings and Pence:

Similar posts

Back soon

Comments