5 August 1605: Debauched and ruined, Walter Calverley is crushed to death today at York for the murder of two sons at Calverley Hall (Bradford), but is revived by 1830s schoolboy ghost-raisers as the Rev. Samuel Redhead (age ca. 55)

Phantom. 1874/03/28. Calverley Forty Years Ago. Bradford Observer. Bradford. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

I have for a long time felt a desire to put down a few facts and data connected with and relating to rural life in the West Riding of Yorkshire. The time I have selected is about forty years ago. Before the days of railroads and telegraphy, at the time I refer to, the thought of electing a school board had never entered into the head of the most sanguine politician. There had been a dawning of a plan of education at New Lanark, and close upon that the Reform Bill had become an established fact. The schoolmaster was almost as a rule selected and qualified for his office on account of some physical defect, and as not being eligible for work of any other kind. I had my small amount of education to take at the hands of such, but out of respect to them, I will pass at once to the curriculum of knowledge that was administered to the youth of this country at the date above-mentioned, and also to qualify the conditions, I am wishful to say that the school was a mile away from Apperley Bridge, and about “twenty happy boys” used to roam through woods and green fields to that Parnassus of learning, armed with Markham’s spelling book. A number of sentences had to be committed to memory, marked out with the thumb nail of the tutor, lead pencils being scarce; also there was a dose of Lindley Murray’s Grammar to gulp down. The great lesson books were the English Reader, and Goldsmith’s History of England. Walkingham’s “Tutor” was the stock book, that from that time to the present has formed the great ladder of learning by which the clerks of the last half-century have had to be trained. The ferrule was a part of discipline that has left an impression; we also had to hold up a black oak block of wood occasionally overhead, having to stand on one leg during the operation. There was a great run of superstition, and the belief in apparitions and ghosts was very prevalent. I well remember some of the traditionary stories that I heard at that early date, which have left indelible marks that cannot be effaced even at the present time. I should like to relate a few experiences of the haunted world of spirits as set down before the “Medium” and “Daybreak” was thought of, or Maskelyne and Cook brought seeming evidence of the world of spirits. The ghost that I was best acquainted with was that of “Old Calverley,” who in his lifetime had been the redoubtable Sir Walter Calverley, who was pressed to death at York in the reign of King James, of whom report says he was conjured down under a broad stone in Calverley Wood Lane, the crossing of which at night-fall used to bring on a kind of tremor that one does not forget in a hurry. There is a bloody hand in the centre of the escutcheon of the Calverleys and Blacketts; also there is a play called the Yorkshire Tragedy, in which is an account of this said Old Calverley; but the part I am most anxious to depict is the raising of the veritable ghost of this jealous and infuriated man. The modus operandi was as follows. About a dozen of the scholars having leisure, and fired with the imaginative spirit, used to assemble after school hours close to the venerable old church of Calverley (before the innovation of restoring and dismantling these places was allowed), and there we used to put down on the ground our hats and caps in a pyramid form. Then taking hold of each other’s hands we formed a “magic circle,” holding firmly together and making use of an old refrain-

“Old Calverley, old Calverley, I have thee by ‘th ears, I’ll cut thee in collops unless thou appears.”

While this incantation was going on, crumbs of bread (left from our dinners) were strewed on the ground, mixed with pins, while at the tune we tramped round in the circle with a heavy bread, and some of the more venturesome had to go round to all the church doors and whistle aloud through the keyhole, uttering the bewitching couplet that was being repeated by the other small boys. At this culminating point the figure used to come forth ghostly and pale, in the same manner as the weird sisters in Macbeth and the shadow of Hamlet’s father at Elsinore; for, although old Calverley was conjured down, he was obliged to break open his prison-house. The figure that we saw was like that in the finishing canto of

Don Juan, called Fitz-Fulke. In our hurry to escape detention and to avoid the fearful grasp of a ghost, we used to fall down over each other, our hats and caps being lifted behind a buttress or scattered over ground, while we scampered off afraid of the spirit we had thus called forth.

PHANTOM March, 1874.

Comment

Comment

The first murder was on 23 April 1605. The execution date was 5 August (Lake 1975). It sounds like the author attended the village school at Calverley, like the civil engineer Thomas Rhodes, also from Apperley Bridge, rather than Woodhouse Grove School, also about a mile from Apperley Bridge. I take the apparition to have been the perhaps prematurely aged Rev. Samuel Redhead, born 1778, appointed to Calverley in 1822, renovated its church in 1844, died 1845 (Favell 1846).

Here’s part of A Yorkshire Tragedy, a dramatisation by Thomas Middleton previously attributed to Shakespeare:

HUSBAND.

Oh thou confused man! thy pleasant sins have undone thee, thy damnation has beggerd thee! That heaven should say we must not sin, and yet made women! gives our senses way to find pleasure, which being found confounds us. Why should we know those things so much misuse us?—oh, would virtue had been forbidden! we should then have proved all virtuous, for tis our blood to love that were forbidden. Had not drunkenness been forbidden, what man would have been fool to a beast, and Zany to a swine, to show tricks in the mire? what is there in three dice to make a man draw thrice three thousand acres into the compass of a round little table, and with the gentleman’s palsy in the hand shake out his posterity thieves or beggars? Tis done! I ha dont, yfaith: terrible, horrible misery.— How well was I left! very well, very well. My lands shewed like a full moon about me, but now the moon’s ith last quarter, waning, waning: And I am mad to think that moon was mine; Mine and my fathers, and my forefathers—generations, generations: down goes the house of us, down, down it sinks. Now is the name a beggar, begs in me! that name, which hundreds of years has made this shire famous, in me, and my posterity, runs out. In my seed five are made miserable besides my self: my riot is now my brother’s jailer, my wife’s sighing, my three boys’ penury, and mine own confusion.

[Tears his hair.]

Why sit my hairs upon my cursed head?

Will not this poison scatter them? oh my brother’s

In execution among devils that

Stretch him and make him give. And I in want,

Not able for to live, nor to redeem him.

Divines and dying men may talk of hell,

But in my heart her several torments dwell.

Slavery and misery! Who in this case

Would not take up money upon his soul,

Pawn his salvation, live at interest?

I, that did ever in abundance dwell,

For me to want, exceeds the throws of hell.

[Enter his little son with a top and a scourge.]

SON. What ails you father? are you not well? I cannot scourge my top as long as you stand so: you take up all the room with your wide legs. Puh, you cannot make me afeared with this; I fear no vizards, nor bugbears.

[Husband takes up the child by the skirts of his long coat in one hand and draws his dagger with the other.]

HUSBAND.

Up, sir, for here thou hast no inheritance left.

SON.

Oh, what will you do, father? I am your white boy.

HUSBAND.

Thou shalt be my red boy: take that.

[Strikes him.]

SON.

Oh, you hurt me, father.

HUSBAND.

My eldest beggar! thou shalt not live to ask an usurer bread, to cry at a great man’s gate, or follow, good your honour, by a couch; no, nor your brother; tis charity to brain you.

SON.

How shall I learn now my head’s broke?

HUSBAND.

Bleed, bleed rather than beg, beg!

[Stabs him.]

Be not thy name’s disgrace:

Spurn thou thy fortunes first if they be base:

Come view thy second brother.—Fates,

My children’s blood

Shall spin into your faces, you shall see

How confidently we scorn beggary!

[Exit with his son.]

(Middleton 1608)

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

29 August 1570: On arriving in Yorkshire, Archbishop Grindal declares war on bloody-minded folk-Catholicism

29 August 1570: On arriving in Yorkshire, Archbishop Grindal declares war on bloody-minded folk-Catholicism 27 July 1612: Jennet Preston, the only Yorkshirewoman among the Pendle witches, is found guilty at York of the murder of Thomas Lister of Westby Hall, Gisburn (Ribble Valley)

27 July 1612: Jennet Preston, the only Yorkshirewoman among the Pendle witches, is found guilty at York of the murder of Thomas Lister of Westby Hall, Gisburn (Ribble Valley)

Comment

Comment

The fiscal fatigue caused by the Hundred Years’ War was a cause of the 1343-45 Truce of Malestroit.

Thomas Sheppard is a good starting point for respectively Ravenser and Ravenser Odd:

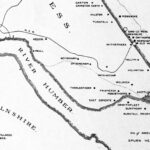

William Shelford … points out that Spurn Point, even in Roman times, must have been 2,250 yards at least beyond the present coastline ; and that at or near this spot the Danes landed in 867, planted their standard “The Raven,” and practically originated the town of Ravensburg, or Ravenser, or Ravenseret, within Spurn Head. The town developed into “one of the most wealthy and flourishing ports of the kingdom. It returned two Members to Parliament, assisted in equipping the navy, had an annual fair of thirty days, two markets a week, is mentioned twice by Shakespeare,[King Henry VI, part iii, Act iv, Scene 7; and Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1] and considered itself honoured by the embarkation of Baliol with his army for the invasion of Scotland in 1332; by the landing of Bolingbroke, afterwards Henry IV, in 1399; and by the landing of Edward IV in 1471, not long after which it was entirely swept away.” Today, we cannot even be certain where the place was. […] In 1296 “Kaiage” [right to tax wharf occupation] was granted to the inhabitants by Edward I. Two years later Ravenser petitioned the king for certain privileges, and offered 300 marks in payment. In 1300 the magistrates of Ravensere were enjoined to stop the export of bullion; in 1305 it sent Members to Parliament. In 1310 Ravensere remonstrated against the depredations of the Earl of Holland, and in the same year Ravenness sent ships for Edward II.’s expedition to Scotland. Two years later the inhabitants were empowered to levy a tax to defend their walls. In 1323 commissions were issued for the “Wapentak of Ravensere.” In 1335-6 warships of Ravensere are referred to, and in 1341 Ravensere sent one Member to “a sort of” naval Parliament of Edward III. In 1346 one ship only was sent by Ravenser to the siege of Calais; (Hull sent 16). In 1355 bodies were washed out of their graves in the chapelyard at Ravenser. In 1361 [i.e. 1362 – the Second St. Marcellus flood] the floods drove the merchants to Hull and Grimsby; and by 1390 nearly all trace of the town, as such, was gone.* In 1413 a grant was made for the erection of a hermitage at Ravenscrosbourne, and in 1428 Richard Reedbarowe, the hermit of the chapel of Ravensersporne obtained a grant to take tolls of ships for the completion of his light-tower. In 1538 Leland refers to Ravenspur in his ” Itinerary,” which seems to be the last reference to the place. As pointed out elsewhere, the place is not included in Holinshed’s ” List of Ports and Creeks,” which was issued before 1580.

[…]

Ravenser-odd (also referred to as Odd near Ravenser, Ravenserot, Ravensrood, Ravensrodd, Ravensrode, etc.), probably originated in the early part of the thirteenth century, soon after Ravenser, the adjoining port, came to be of importance. Ravenser-odd was apparently built on an island.

In 1251 some monks obtained half an acre of ground on which to erect buildings for the preservation of fish, in the burg of Od near Ravenser. The chronicler of Meaux wrote that “Od was in the parish of Esington, about a mile distant from the mainland. The access to it was from Ravenser by a sandy road covered with round yellow stones, scarcely elevated above the sea. By the flowing of the ocean it was little affected on the east, and on the west it resisted in a wonderful manner the flux of the Humber.”

In 1273 there was a dispute about a chapel at Od, and this was carried on for some time.

In 1300 Edward I. gave some lands in Ravenserodde to the convent of Thornton in Lincolnshire, and others to St. Leonard’s Hospital, York.

In 1315 the burgesses of Ravenserod agreed to pay the king £50 for the confirmation of their charters, and “Kaiage” for seven years. In 1326 the king granted dues and customs in the port of Ravenserod, and about 1336 William De-la-Pole left Ravenserod for Hull. Ravenserode sent a representative to Edward III.’s “naval Parliament” in 1344, as well as a man well versed in naval affairs.

In 1346 Ravensrodde was one of the places mentioned by the Abbot of Meaux as suffering by the sea. In the following year it was frequently inundated, and in 1360 [presumably 1362] “Ravenser Odd was totally annihilated by the floods of the Humber and inundations of the great sea.”

In 1355 the bodies in the chapel yard, which, “by reason of inundations were then washed up and uncovered,” were removed and buried in the churchyard at Easington.

About this time we read the following curious note in the Meaux Chronicle : — ” When the inundations of the sea and of the Humber had destroyed to the foundations the chapel of Ravenserre Odd, built in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so that the corpses and bones of the dead there buried horribly appeared, and the same inundations daily threatened the destruction of the said town, sacrilegious persons carried off and alienated certain ornaments of the said chapel, without our due consent, and disposed of them for their own pleasure ; except a few ornaments, images, books, and a bell which we sold to the mother church of Esyngton, and two smaller bells to the church of Aldeburghe. But that town of Ravenserre Odd, in the parish of the said church of Esyngton, was an exceedingly famous borough, devoted to merchandise, as well as many fisheries, most abundantly furnished with ships and burgesses amongst the boroughs of that sea-coast. But yet, with all inferior places, and chiefly by wrong-doing on the sea, by its wicked works and piracies, it provoketh the wrath of God against itself beyond measure. Wherefore, within the few following years, the said town, by those inundations of the sea and of the Humber, was destroyed to the foundations, so that nothing of value was left.”

Notwithstanding this, “In the Hedon inquisition of January 1401, the chapel of Ravenserodde, with the town itself, was declared to be worth, in spiritualities, more than £30 per annum.”

William Wheater treads a similar path, perhaps better – haven’t read it (Wheater 1889).

The rise and fall of a tsunami are among the 15 signs of doom in a Middle English poem, The Pricke of Conscience, and are illustrated in a medieval (ca. 1410) window in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York:

Þe first day of þas fiften days,

Þe se sal ryse, als þe bukes says,

Abowen þe heght of ilka mountayne,

Fully fourty cubyttes certayne,

And in his stede even upstande,

Als an heghe hille dus on þe lande.

Þe secunde day, þe se sal be swa law

Þat unnethes men sal it knaw.

Þe thred day, þe se sal seme playn

And stand even in his cours agay[n],

Als it stode first at þe bygynnyng,

With-outen mare rysyng or fallyng

(Anon 1863)

Britta Sweers, “Trutz, Blanke Hans” – Musical and Sound Recollections of North Sea Storm Tides in Northern Germany

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter