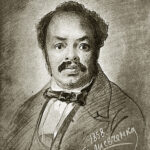

26 June 1794: The editor of the Sheffield Register fires off a final broadside against Georgian despotism, and flees to the continent and thence to the United States

Willis G. Briggs. 1907. Joseph Gales, Editor of Raleigh’s First Newspaper. The North Carolina Booklet, Vol. 7. Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina Daughters of the American Revolution. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

In 1787 Gales began the publication of The Sheffield Register, a weekly newspaper, and ardently championed reform. He warmly welcomed the French revolution. The English ministry, under leadership of Pitt, soon resorted to severe measures to repress the liberal wave, fearing that it would bring calamity to the monarchy.

[…]

A study of the file of The Sheffield Register of 1794 reveals no policy which the enlightened twentieth century would not applaud. Joseph Gales’ clear convictions gleam in his brief editorials. His sympathy was openly expressed for the two hundred wretched debtors confined in Lancaster Castle, with accommodation for only eighty persons, two sleeping in a bed. When a fifteen-year-old girl was hung for the murder of her grandfather the editor grieved because the child had been given no chance and was so ignorant and wretched as not to know right from wrong. Again he remonstrates on the severity of the law when a farmer in March, 1794, was sentenced to die for shooting a neighbor’s foal. The Sheffield editor applauded “the glorious example” of the jury, which refused five times to obey the mandates of the court and persisted in a verdict of “not guilty” in the case of Robert Erpe, charged with speaking libel in that he criticised the Pitt ministry. “Twelve gold medals” ought to be presented to those jurors, declared Gales.

[…]

Monday, April 7, 1794, was a field day for the “friends of justice, of liberty and of humanity” in Shefiield. Henry Redhead Yorke, a young man of great promise, a graduate of Cambridge, a protege of Edmund Burke, had announced his allegiance to the Liberal cause after a visit to Paris, where he met leaders of the Jacobin clubs. He was hailed as an invaluable ally, and the Constitutional Society and the Society of the Friends of the People at Shefiield endorsed the young man for parliament. Twelve thousand reformers on this April day assembled on Castle Hill, listened to a stirring speech by Yorke and adopted an address. This address, briefly stated, asserted: (1) The people were the true source of government; (2) freedom of speech is a right which cannot be denied; (3) condemnation without trials is incompatible with free government; (4) where the people have no share in the government taxation is tyrrany; (5) a government is free in proportion as the people are equally represented. The address “demanded as a right,” and no longer asked as a favor, “universal representation.” It concluded with a lengthy petiton not only for “abolition of the slave trade” but for “emancipation of negro slaves” in the British West Indies. The mechanics of Sheffield were wrought to a pitch of highest enthusiasm. Horses were unhitched and the carriage, containing Yorke, the candidate, and Joseph Gales, secretary of the meeting and probably author of the address adopted, was drawn in triumph through the town by the multitude.

[…]

The Committee of Secrecy, appointed by parliament to investigate rumored conspiracies, made a report May 23, 1794, of such a character that the Pitt ministry immediately suspended the habeas corpus act, a course almost without precedent in time of peace. The committee found that there existed “The Society for Constitutional Information” and “The London Corresponding Society” and that these societies had by resolution “applauded the publication of a cheap edition of ‘The Rights of Man,'” and voted addresses to the Jacobins at Paris and to the National Convention of France.

Continuing, the report said “The circumstance which first came under the observation of your committee containing a distinct trace of measures of this description, was a letter from a person at Sheffield, by profession a printer (who has since absconded), which was thus addressed ‘Citizen Hardy, Secretary of the London Corresponding Society’, which was found in the possession of Hardy on the twelfth of May, last, when he was taken into custody.” The letter was dated from Sheffield April 20, 1794, on paper from “Gales’ printing office” and the objectionable portion of the communication was as follows: “Fellow Citizens: The barefaced aristocracy of the present administration has made it necessary that we must be prepared to act on the defensive against any attack they may command their newly armed minions to make upon us. A plan has been hit upon, and, if encouraged sufficiently, will, no doubt, have the effect of furnishing a quantity of pikes to the Patriots, great enough to make them formidable.” This was the only reference to resistance or force in the letter. With Hardy’s paper was also found an account of a meeting at Sheffield where a full chorus sang a hymn written by James Montgomery.

When the news that the right of habeas corpus had been suspended reached Sheffield Gales exclaimed in his paper “every wretch who has either through malice or envy a dislike to his neighbor will have now an opportunity of gratifying his malicious intentions.” Warrants were issued for Yorke, Gales and others, charged with treasonable and seditious practices, and the Sheffield editor knew that the time had come when he must either seek safety elsewhere or be delivered to his enemies.

The Sheffield Register of June 26, 1794, contains the editor’s farewell. In this address he wrote: “The disagreeable predicament in which I stand, from the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, precludes me the Happiness of staying among you, My Friends, unless I would expose myself to the Malice, Enmity and Power of an unjust Aristocracy. It is in these persecuting days, a sufficient Crime to have printed a newspaper which has boldly dared to doubt the infallibility of ministers, and to investigate the justice and policy of their measures. Could my imprisonment, or even death, serve the cause which I have espoused — the cause of Peace, Liberty and Justice — it would be cowardice to fly from it; but, convinced that ruining my family and distressing my friends, by risking either, would only gratify the ignorant and the malignant, I shall seek that livelihood in another state which I can not peaceably attain in this.” He reviews his course : “I was a member of the Constitutional Society,” he admits, “and shall never, I am persuaded, whatever may be the final result, regret it, knowing that the real as well as ostensible object of this society, was a rational and peaceable reform in the representation of the people in parliament. The Secret Committee has imputed to the Society intentions of which they had no conceptions and crimes which they abhor. It has been insinuated, and, I believe, pretty generally believed, that I wrote the letter which is referred to by the Secret Committee, concerning the pikes. This charge, in the most unequivocal manner, I deny. I neither wrote, dictated or was privy to it. It will always be my pride, that I have printed an impartial and truly independent newspaper, and that I have done my endeavors to rescue my countrymen from the darkness of Ignorance and to awaken them to a just sense of their privileges as human beings, and, as such, of their importance in the grand scale of creation.”

Ten years later in America, when a rival accused Gales of having been indicted in England, he replied in his paper, “If it be deemed a crime to have opposed by means of a free press, governmental usurpation on the rights of the people, I plead guilty.”

Comment

Comment

Leader’s Sheffield reminiscences tell a similar tale (Leader 1876).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

Comment

Comment

Via Chris Hobbs, who has traced some of Colgrave’s life and death, but doesn’t seem to have met with the following sensational account by Tim Carew of the events of 30 October 1914:

This preamble leads up to one story of what happened during the fighting round Messines.

A certain sector of the line became untenable, and the order came from the 3rd Cavalry Brigade for a general retirement. The orders did not reach Captain Forbes, commanding the Punjabi Mussulman Company of the 57th Rifles, and they were attacked frontally, from both flanks and surrounded. They fought back valiantly with bayonets, rifle butts, boots and fists, but Captain Forbes received severe wounds from which he subsequently died and Lieutenant Clarke was killed. A bare half company – some forty men in all – managed to escape.

All the Indian officers had become casualties, and there was no one above the rank of naik left alive in the company: the bugbear of jimmiwari was ruthlessly exposed.

Obeying some herd instinct the survivors sought the temporary shelter of a shell-torn barn, where they huddled together in miserable groups, awaiting what fate had in store for them.

It may seem that the conduct of these men was not entirely creditable. They had no British officers and no orders; they did not know where they were. But one and all had fought with the greatest gallantry against an enemy who had outnumbered them by something like ten to one; they were not afraid, they simply did not know what to do. They needed a leader, and they needed him quickly.

They were soon to get one, in the improbable shape of Corporal Colgrave of the 5th Lancers.

Colgrave was a Kiplingesque character. Once, a long time ago, he had been a Squadron Quartermaster-Sergeant. But a fondness for liquor, first in a trickle, and then in a rush, had brought him down. He claimed intimate acquaintance with General Allenby, which was true in a way because Allenby, when Commanding Officer of the 5th Lancers, had ‘busted’ Colgrave to the ranks.

Now Corporal Colgrave was climbing the weary promotion ladder once more. His officers had looked for qualities of leadership in him and looked in vain; it seemed almost certain that the two stripes he wore, precarious at that, represented the peak of his promotion prospects.

Colgrave and a squad of a dozen men had been looking after horses about a mile in rear of Messines, when an urgent order summoned them forward to a point in the line where the addition of thirteen more rifles would be of incalculable value. The barn on which they happened looked tempting, and Corporal Colgrave ordered five minutes’ halt for a smoke.

‘Got a fag, Corp?’ asked a trooper hopefully outside the barn. ‘Only got one,’ said Colgrave.

‘I only want one.’

‘Less of your lip. Get inside.’

Corporal Colgrave had done many years’ service in India, and regaled newly-joined young soldiers with largely untrue stories of gory encounters on the North-West Frontier against the wily ‘Paythan’, massive commercial deals in bazaars and gargantuan copulation in native brothels. Like many another vintage British soldier, he was firmly convinced that he was a fluent speaker of Hindustani.

The Lancers entered the barn and gazed upon forty miserable Indian faces; when he is really downcast, no race of man can wear a darker mask of woe than an Indian.

‘Blimey, what a bunch,’ said the corporal; then loudly, ‘Sab thik hai idher?’

Clearly, everything was very far from being ‘thik‘. The Indians eyed him warily and without enthusiasm. On the other hand, although he was not a Sahib he had a white face and wore the two stripes of a naik and might take on the jimmiwari.

‘Kis waste this ‘ere? asked Colgrave. ‘Sahib kidher hai?’

‘Sahib margya,’ said a dozen sad voices.

‘Well, blimey,’ said Colgrave, in trouble with the language already, ‘you want to marrow the fuckin’ Germans, don’t you, malum?’

The idea was beginning to catch on. ‘Jee-han!’ said a dozen voices.

Corporal Colgrave winked at the other Lancers, one of whom was heard to say ‘old Charlie fancies ‘isself as a fuckin’ general’.

Smiles were beginning to appear on downcast brown faces; there was something about the gamey, ribald approach of Corporal Colgrave which seemed to be a positive denial of defeat. Murderous shelling, which had blown men to pieces and buried men alive, had taken some of the heart out of the Punjabi Mussulmans, but Colgrave was putting it back.

‘Right, then, you miserable-looking lot of buggers,’ said Corporal Colgrave with affection, ‘idher ao: Abhi wapas, got it? Marrow all the German soors. Abhi thik hai?’

‘Thik hai!’ said forty voices in unison.

‘Achi bat. Now, then, who’s going to win the bleedin’ V.C.? Chalo!’

And so thirteen Lancers went into the line, with the priceless addition of forty by now one-hundred-per-cent belligerent Indians, and that particular sector of line was held for the next twenty-four hours.

(Carew 1974)

Carew’s footnote:

Some sort of glossary of this strange conversation is required. Sab thik hai idher is ‘everything all right here?’ (clearly it was not); margya is dead; malum, literally translated, means ‘know’; jee-han is ‘yes’; idher ao is ‘come here’; abhi wapas roughly means ‘we are going back now’; achi bat, in the language of a British N.C.O., can be construed as ‘right, then’; chalo, literally translated means ‘dive’, but in this context can be taken as meaning ‘let’s go’; ‘kis waste this ‘ere’ almost explains itself – it is ‘what’s going on here, then?’, the rhetorical question asked by English policemen in almost any circumstance.

Who was his source? Not everybody trusts him!

Ciarán Byrne says that Colgrave’s band were also from the 129th Baluchis, but I trust Carew more. I think that, in General Willcocks’s discussion of the 57th at Hollebeke, Colgrave is the officer referred to here:

It is instructive to read in the reports that some of the men in Messines “had the good fortune” to come across an officer who spoke Hindustani, and was thus able to direct them to rejoin their Headquarters (Willcocks 1920).

Khudadad Khan of the 129th Baluchis won a VC on the following day:

In October 1914, when the Germans launched the First Battle of Ypres, the newly arrived 129th Baluchis were rushed to the frontline to support the hard-pressed British troops. On 31 October, two companies of the Baluchis bore the brunt of the main German attack near the village of Gheluvelt in Hollebeke Sector. The out-numbered Baluchis fought gallantly but were overwhelmed after suffering heavy casualties. Sepoy Khudadad Khan’s machine-gun team, along with one other, kept their guns in action throughout the day, preventing the Germans from making the final breakthrough. The other gun was disabled by a shell and eventually, Khudadad Khan’s own team was overrun. All the men were killed by bullets or bayonets except Khudadad Khan who, despite being badly wounded, had continued working his gun. He was left for dead by the enemy but managed to crawl back to his regiment during the night. Thanks to his bravery, and that of his fellow Baluchis, the Germans were held up just long enough for Indian and British reinforcements to arrive. They strengthened the line, and prevented the German Army from reaching the vital ports; Khan was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Khan also figures in Carew.

Michael Keary has some excellent excerpts from the letters of Henry D’Urban Keary, who commanded an Indian Division on the Western Front, e.g.

Douglas Haig and French hate the Indian Army and want to get rid of the whole thing… No recognition of anything good … I think no-one in the Indian Corps feels safe or induced to do his best… I suppose this is the penalty for going into the Indian Army and having the bad luck to be sent to France where we are in a minority, rather than to Egypt or Dardanelles where they are equal or a majority (Keary 2021).

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter