19 October 1816: Serenaded by the military, decorated barges leave Leeds for Liverpool to celebrate the completion, after almost 50 years, of the canal uniting east and west

Glorious present, glorious past: Turner’s image eight years later of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal sets off Ephraim Elsworth’s maltings(?), the Ellers/Ellars, Ellers Bridge, and Kirkstall Lock against the ruins of Kirkstall Abbey (Turner 1981).

Leeds Mercury. 1816/10/26. Completion of the Leeds and Liverpool canal. Leeds. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

On Saturday morning at seven o’clock, several of the proprietors of the Canal, accompanied by a number of friends, proceeded in an elegant barge, from the basin of the Canal to the Bridge over the Aire, to commence at that point their voyage to Blackburn, to open that part of the Canal which was still wanting to complete the communication with Liverpool. This vessel was accompanied by a barge belonging to the Union Company, splendidly decorated with flags and streamers. The sailing of the vessels was announced by a discharge of cannon, and the barges entered the canal amidst the discharge of artillery, the animating strains of a full military band, and the acclamations of an immense number of spectators, which lined the banks of the canal for a great distance. On entering the first lock, the band struck up the national air of “God save the King.” The barge of the proprietors bore a flag, in which was inscribed the name of ‘John Hustler,’ the engineer, under whose superintendence a considerable part of the work had been completed. It was intended that another barge belonging to the proprietors, called the Joseph Priestley should have taken part in the procession, but some mischance which happened to it on its voyage to Leeds defeated this part of the plan; all the sloops in the basin were decorated with streamers, and the whole formed a truly animated and delightful scene. It was under these favourable auspices that the two barges proceeded on their route to Liverpool, attended by the military band, who gratified the immense number of persons who followed their route, with playing the most popular airs, marches, &c. It was not an uninteresting theme to endeavour to review the different feelings with which this scene was contemplated by the persons assembled. Many, no doubt, viewed it merely as a splendid and novel spectacle, whilst others contemplated it as the finishing of a great national work, of which they remembered not the beginning: others again associated with the memory of its commencement the earliest recollections of their boyish days; whilst a few, alas, how few, rejoiced in the completion of an undertaking, in the very first stages of which they had taken a lively interest when in the full bloom and vigour of life, to which period this scene would irresistibly carry back their thoughts (a period of nearly fifty years,) which, though brief in the review has been full of important incidents. But it was to all a scene of great interest, and afforded evident satisfaction to the immense multitude that witnessed it.

Our notice of the rest of the voyage must for the present be very brief-The barges reached Skipton on Saturday evening, and on the following day arrived at Burnley. On Monday, about three o’clock in the afternoon, they entered Blackburn, having in their train a number of other vessels. The proprietors and their friends, &c. proceeded with flags and music to the New Inn, where they sat down to an excellent dinner. The bells rung a merry peal, and the afternoon was spent with the utmost harmony and satisfaction. On Tuesday morning, at eight o’clock, all the arrangements being completed, the proprietors’ barge, attended by the sloop of the Union Company, and a number of other vessels decorated with flags, streamers, &c. and crowded with persons of the greatest respectability, entered the new part of the canal amidst the discharge of cannon, and the heartfelt cheering of an immense number of spectators. In the evening the procession reached Wigan, and on Wednesday this interesting ceremony was completed by the arrival of the voyagers at the Basin of the Canal at Liverpool about five o’clock in the evening.

As the aquatic procession passed through the different villages on the banks of the canal, it continued to be greeted with new spectators; nor was it unamusing, as the scene changed, to trace the different costume and manners of these various assemblages. The whole of the voyage was one indeed of peculiar interest, and frequently of great hilarity, and the populace, however noisy and uncouth their expressions of joy might occasionally be, manifested undeviating good humour, to which indeed the politeness, hospitality, and good humour of those who had the management of this procession, did not a little contribute.

Comment

Comment

H/t to the Leeds & Liverpool Canal Society. Their article also contains an excerpt from the Mercury of 1777/06/10 describing the opening ceremony of the Leeds-Gargrave segment on 1777/06/04, not reproduced here. Joseph Priestley (<1741-1817) was superintendent of Leeds & Liverpool Canal Co. for nearly 50 years, and is not to be confused with the Birstall-born scientist and theologian. The lock is apparently 1770-77, the bridge 1800.

The Ellars/The Ellers/Ellers Cottage and J.M.W. Turner

Chapel Allerton estate agents Fowler & Powell claim that the big house on the left of Turner’s image is the same as the one they are keen to shift in summer 2025:

No1. THE ELLERS Historic City Home. Leeds & Bradford Rd LS5

Introduction

Introducing a home that embodies the essence of being ‘steeped in history’ while also serving as ‘the perfect family home.’ This property and plot perfectly combine period charm with modern luxury. Sitting on the bank of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal is No.1 The Ellers – or Ellers house as it is referred to in Turners painting – an imposing historical building and, most importantly, a five-bedroom family home that is perfectly ready to move into. We’re delighted to welcome you to explore No.1 The Ellers in West Leeds.

Historical Significance

The Ellers was built in the early 1800s as a malting house, producing malt for a nearby brewery, but was not named until some years later. The home holds a claim to fame as it sits in a landscape painting by the famous landscape artist Joseph Turner in 1824-5 positioned in the prestigious Tate Gallery. Turner was London-based but would travel around the UK in the summer months, capturing scenes that inspired him. In his watercolour, he captured a barren Kirkstall Abbey with the bustling canal used for transportation, particularly in the textile industry, with one building standing proudly in the image – The Ellers. Framed clippings and photographs detailing the property’s remarkable history and transformation journey can be found displayed around the ground floor of the home.

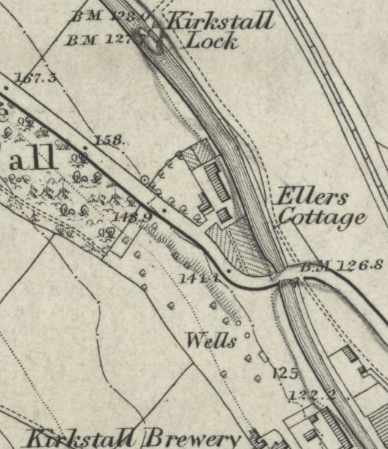

Even for an estate agent this is pretty silly. Kathleen Gurney has established that the original house, stables, and maltings with direct access to the canal were built by around 1820 on ground already known as the Ellers by an Armley maltster, Peter Tattersall, who was married to her great-great aunt, Mary Cooper (Gurney 1998). I think this is the curious house – see the window alignment and the apparent lack of chimneys on the cold north side – shown on the 1842 OS, and the ground plan appears consistent with Turner’s house:

However, the three-storey house in the early-century vernacular depicted by Turner is clearly not the two-storey late-19th-century house with an H layout(?) visible in 1952 in the background following a road accident:

Shayne Niemen, the architect for the 2004 redevelopment, claims to believe that, despite obvious fundamental differences, the two houses are the same in some sense: “When the planners told us the building was in a Turner painting, restoring it immediately became the number one priority.” However, and I think this is Niemen again, “at some point in the 19th century, the building was … given a new [sandstone] façade, obscuring the gable end visible in … Turner’s watercolour” (Greenwood 2004/02/11). This patent nonsense is presumably the source of the estate agents’ claims. The following two shots, the first from the 2004 architect’s website, the second from Google Maps, may show different stone used in the south-facing cottage (left) and the crossbar of the H, but barring any structural evidence to the contrary, I’m guessing that is a consequence of reuse of stone from the early century building(s):

I think the history went something like this. In the late-ish 19th century, after the original family had moved out (in the 1840s, according to Gurney), the 1810s house was demolished and replaced, starting from scratch (Regency houses tend to be short on foundations), by a south-facing cottage, which was faced with more fashionable and more readily available (canals, railways) fine-grained sandstone from the Pennine Coal Measures (I hope I’m not misinterpreting Graham Lott (Lott 2012)), and which took advantage of the many technological improvements in house construction since the Napoleonic Wars (e.g. flush toilets became common mid-century) Some of the coarser-grained Millstone Grit sandstone may have been reused in the crossbar and rear vertical of the H layout visible in the 1952 photo. Perhaps the rebuild was by the prosperous Leeds draper, George Francis Crowe (1833/4-1909), who was living at The Ellars on Bradford Road, Kirkstall (continuation of Bridge Road) by 1888. The lack of listing suggests to me that the experts believe there to be no historical association. (Erkulis incorrectly says that it is Grade-II listed, though the bridge and lock are.)

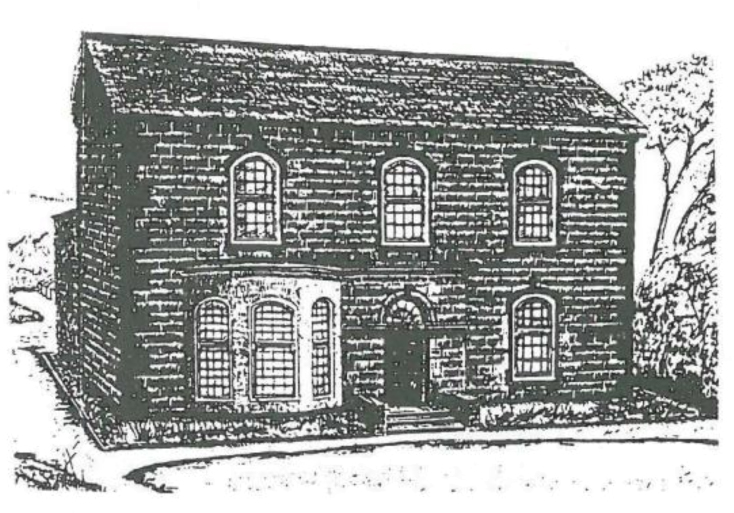

The modern house has much in common with the late 19th century one, but the chimneys (which you will note are in a different location from Turner’s) and the rear vertical of the H (industrial function?) had gone by the time Ian Thornton produced the sketch reproduced in Gurney’s piece:

And the garage to the left of the front façade is even newer.

Martin Erkulis, the developer, struggling with the evident contrast between the houses worked on by himself and Turner, decided that Turner’s was simply an invention: “Although the house that Turner depicted has three storeys, Erkulis says there is no evidence that it ever had three floors above ground. ‘At one end of the property is a basement with a vaulted ceiling which will have a window looking out to the front,’ he says. ‘But whether Turner painted from sketches or used artistic licence, we don’t know.’” And on his own site, Erkulis says it is Georgian – presumably in a general historical sense rather than in terms of any stylistic traits.

I think Turner for artistic effect foreshortens the scene and exaggerates height differentials in the landscape (Dover (1825) is the most notorious example of this latter practice of his), but why would he paint the wrong house into an otherwise reasonably verosimil scene, a scene which would probably be familiar to the Fawkes family at Farnley Hall, his principal local clients?

Stuff:

- Greenwood has a puzzling quote from David Hill, then Professor of Fine Art at Leeds University, and a prolific writer on Turner. No, an ellars isn’t “a place where elm trees grow”: an eller is an alder – see the OED entry (“common on riverbanks and damp woodland”) and Thoresby’s confirmation (Thoresby 1715). It is true that when Crowe sent his son to Rugby, the address was listed as The Elms, and there were elms along the Aire at Kirkstall, but that doesn’t affect the meaning of ellers/ellars.

- I hoped in vain to find something in Lidar.

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

23 January 1643: Thomas Fairfax, the Rider of the White Horse, captures Leeds from the Beast with the help of Psalm 68

23 January 1643: Thomas Fairfax, the Rider of the White Horse, captures Leeds from the Beast with the help of Psalm 68 1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington

1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington

Comment

Comment

A letter written Tuesday 6 July 1858 describes the real-life events of Sunday 4:

“Here I am still (after having been to church at Horton in Ribblesdale). All that I have heard of the grandeur of Godale Scar and Malham Cove, was, I found, not exaggerated. The awful cliff filling up the valley with a sheer cross wall of 280 feet, and from beneath a black lip at the foot, the whole river Air coming up, clear as crystal, from unknown abysses. Its real source is, I suppose, in the great lake above, Malham Tarn, on which I am going to-morrow. The fishing is the best in the whole earth. Last night we went up Ingleborough, 2380, and saw the whole world to the west, the lake mountains, and the western sea beyond Lancaster and Morecambe Bay for miles. There was a cap on Scawfell forty miles away which has ended in heavy rain to-day. The people are the finest I ever saw-tall, noble, laconic, often very handsome. Very musical too, the women with the sweetest voices in speech which I have ever heard. I trust Rose has got her letter; I sent it down to Settle by a man (Kingsley 1878).

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter