25 September 1066: The Stamford Bridge massacre by Harold Godwinson’s army of Harald Hardrada and Tostig Godwinson’s force – symbol of the end of the Viking Age

The roughly contemporaneous sundial at St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, tells of the church’s reconstruction by Gamal’s son Orm at the time of Edward the Confessor and Earl Tostig, murderer of Gamal (Wall 1912).

James Ingram, Ed. 1823. The Saxon Chronicle. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. What we now call The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

A.D. 1066. This year came King Harold from York to Westminster, on the Easter succeeding the midwinter when the king [Edward the Confessor] died. Easter was then on the sixteenth day before the calends of May. Then was over all England such a token seen as no man ever saw before. Some men said that it was the comet-star, which others denominate the long-haired star. It appeared first on the eve called Litania major, that is, on the eighth before the calends of May; and so shone all the week.

Soon after this came in Earl Tosty from beyond sea into the Isle of Wight, with as large a fleet as he could get; and he was there supplied with money and provisions. Thence he proceeded, and committed outrages everywhere by the sea-coast where he could land, until he came to Sandwich. When it was told King Harold, who was in London, that his brother Tosty was come to Sandwich, he gathered so large a force, naval and military, as no king before collected in this land; for it was credibly reported that Earl William from Normandy, King Edward’s cousin, would come hither and gain this land; just as it afterwards happened.

When Tosty understood that King Harold was on the way to Sandwich, he departed thence, and took some of the boatmen with him, willing and unwilling, and went north into the Humber with sixty skips; whence he plundered in Lindsey, and there slew many good men. When the Earls Edwin and Morkar understood that, they came hither, and drove him from the land. And the boatmen forsook him. Then he went to Scotland with twelve smacks; and the king of the Scots entertained him, and aided him with provisions; and he abode there all the summer. There met him Harold, King of Norway, with three hundred ships. And Tosty submitted to him, and became his man.

Then came King Harold to Sandwich, where he awaited his fleet; for it was long ere it could be collected: but when it was assembled, he went into the Isle of Wight, and there lay all the summer and the autumn. There was also a land-force everywhere by the sea, though it availed nought in the end. It was now the nativity of St. Mary, when the provisioning of the men began; and no man could keep them there any longer. They therefore had leave to go home: and the king rode up, and the ships were driven to London; but many perished ere they came thither.

When the ships were come home, then came Harald, King of Norway, north into the Tine, unawares, with a very great sea-force – no small one; that might be, with three hundred ships or more; and Earl Tosty came to him with all those that he had got; just as they had before said: and they both then went up with all the fleet along the Ouse toward York.

When it was told King Harold in the south, after he had come from the ships, that Harald, King of Norway, and Earl Tosty were come up near York, then went he northward by day and night, as soon as he could collect his army. But, ere King Harold could come thither, the Earls Edwin and Morkar had gathered from their earldoms as great a force as they could get, and fought with the enemy [Battle of Fulford, 20 September 1066]. They made a great slaughter too; but there was a good number of the English people slain, and drowned, and put to flight: and the Northmen had possession of the field of battle.

It was then told Harold, king of the English, that this had thus happened. And this fight was on the eve of St. Matthew the apostle, which was Wednesday. Then after the fight went Harold, King of Norway, and Earl Tosty into York with as many followers as they thought fit; and having procured hostages and provisions from the city, they proceeded to their ships, and proclaimed full friendship, on condition that all would go southward with them, and gain this land.

In the midst of this came Harold, king of the English, with all his army, on the Sunday, to Tadcaster; where he collected his fleet. Thence he proceeded on Monday throughout York. But Harald, King of Norway, and Earl Tosty, with their forces, were gone from their ships beyond York to Stanfordbridge; for that it was given them to understand, that hostages would be brought to them there from all the shire.

Thither came Harold, king of the English, unawares against them beyond the bridge; and they closed together there, and continued long in the day fighting very severely. There was slain Harald the Fair-haired, King of Norway, and Earl Tosty, and a multitude of people with them, both of Normans and English; and the Normans that were left fled from the English, who slew them hotly behind; until some came to their ships, some were drowned, some burned to death, and thus variously destroyed; so that there was little left: and the English gained possession of the field.

But there was one of the Norwegians who withstood the English folk, so that they could not pass over the bridge, nor complete the victory. An Englishman aimed at him with a javelin, but it availed nothing. Then came another under the bridge, who pierced him terribly inwards under the coat of mail. And Harold, king of the English, then came over the bridge, followed by his army; and there they made a great slaughter, both of the Norwegians and of the Flemings.

But Harold let the king’s son, Edmund, go home to Norway with all the ships. He also gave quarter to Olave, the Norwegian king’s son, and to their bishop, and to the earl of the Orkneys, and to all those that were left in the ships; who then went up to our king, and took oaths that they would ever maintain faith and friendship unto this land. Whereupon the King let them go home with 24 ships.

These two general battles were fought within five nights.

Meantime Earl William came up from Normandy into Pevensey on the eve of St. Michael’s mass; and soon after his landing was effected, they constructed a castle at the port of Hastings. This was then told to King Harold; and he gathered a large force, and came to meet him at the estuary of Appledore. William, however, came against him unawares, ere his army was collected; but the king, nevertheless, very hardly encountered him with the men that would support him: and there was a great slaughter made on either side. There was slain King Harold, and Leofwin his brother, and Earl Girth his brother, with many good men: and the Frenchmen gained the field of battle, as God granted them for the sins of the nation.

Archbishop Aldred and the corporation of London were then desirous of having child Edgar to king, as he was quite natural to them; and Edwin and Morkar promised them that they would fight with them. But the more prompt the business should ever be, so was it from day to day the later and worse; as in the end it all fared.

This battle was fought on the day of Pope Calixtus: and Earl William returned to Hastings, and waited there to know whether the people would submit to him. But when he found that they would not come to him, he went up with all his force that was left and that came since to him from over sea, and ravaged all the country that he overran, until he came to Berkhampstead; where Archbishop Aldred came to meet him, with child Edgar, and Earls Edwin and Morkar, and all the best men from London; who submitted then for need, when the most harm was done. It was very ill-advised that they did not so before, seeing that God would not better things for our sins. And they gave him hostages and took oaths: and he promised them that he would be a faithful lord to them; though in the midst of this they plundered wherever they went.

Then on midwinter’s day Archbishop Aldred hallowed him to king at Westminster, and gave him possession with the books of Christ, and also swore him, ere that he would set the crown on his head, that he would so well govern this nation as any before him best did, if they would be faithful to him. Nevertheless he laid very heavy tribute on men, and in Lent went over sea to Normandy, taking with him Archbishop Stigand, and Abbot Aylnoth of Glastonbury, and the child Edgar, and the Earls Edwin, Morkar, and Waltheof, and many other good men of England. Bishop Odo and Earl William lived here afterwards, and wrought castles widely through this country, and harassed the miserable people; and ever since has evil increased very much. May the end be good, when God will!

Comment

Comment

Orderic Vitalis:

In the month of August, Harold, king of Norway, and Tostig, with a powerful fleet set sail over the wide sea, and, steering for England with a favourable aparctic, or north wind, landed in Yorkshire, which was the first object of their invasion. Meanwhile, Harold of England, having intelligence of the descent of the Norwegians, withdrew his ships and troops from Hastings and Pevensey, and the other seaports on the coast lying opposite to Neustria, which he had carefully guarded with a powerful armament during the whole of the year, and threw himself unexpectedly, with a strong force by hasty marches on his enemies from the north. A hard-fought battle ensued, in which there was great effusion of blood on both sides, vast numbers being slain with brutal rage. At last the furious attacks of the English secured them the victory, and the king of Norway as well as Tostig, with their whole army, were slain. The field of battle may be easily discovered by travellers, as great heaps of the bones of the slain lie there to this day, memorials of the prodigious numbers which fell on both sides.

While however the attention of the English was diverted by the invasion of Yorkshire, and by God’s permission they neglected, as I have already mentioned, to guard the coast, the Norman fleet, which for a whole month had been waiting for a south wind in the mouth of the river Dive and the neighbouring harbours, took advantage of a favourable breeze from the west to gain the roads of St. Valeri. While it lay there innumerable vows and prayers were offered for the safety of themselves and their friends, and floods of tears were shed. For the intimate friends and relations of those who were to remain at home, witnessing the embarkation of fifty thousand knights and men-at-arms, with a large body of infantry, who had to brave the dangers of the sea, and to attack an unknown people on their own soil, were moved to tears and sighs, and full of anxiety both for themselves and their countrymen, their minds fluctuating between fear and hope. Duke William and the whole army committed themselves to God’s protection, with prayers, and offerings, and vows, and accompanied a procession from the church, carrying the relics of St. Valeri, confessor of Christ, to obtain a favourable wind. At last when by God’s grace it suddenly came round to the quarter which was the object of so many prayers, the duke, full of ardour, lost no time in embarking the troops, and giving the signal for hastening the departure of the fleet. The Norman expedition, therefore, crossed the sea on the night of the third of the calends of October [29th September], which the Catholic church observes as the feast of St. Michael the archangel, and, meeting with no resistance, and landing safely on the coast of England, took possession of Pevensey and Hastings, the defence of which was entrusted to a chosen body of soldiers, to cover a retreat and guard the fleet.

Meanwhile the English usurper, after having put to the sword his brother Tostig, and his royal enemy, and slaughtered their immense army, returned in triumph to London. As however worldly prosperity soon vanishes like smoke before the wind, Harold’s rejoicings for his bloody victory were soon darkened by the threatening clouds of a still heavier storm. Nor was he suffered long to enjoy the security procured by his brother’s death; for a hasty messenger brought him the intelligence that the Normans had embarked (Ordericus Vitalis 1853).

I rather like Eleanor Parker’s summing up of the end of the C text of the Chronicle:

The last entry in this version of the Chronicle is for 1066, and it contains a memorable cluster of significant events dated to points in the festival year. From Edward the Confessor, spending Christmas in Westminster at ‘Midwinter’ but dead and buried by ‘Twelfth Day’, the year runs through moments of political crisis dated to Easter, harvest and the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, as Harold Godwineson first gained, then fought to keep, the English crown. The last events recorded are a battle in Yorkshire between an English army and the forces of the Norwegian invader, Harald Hardrada, on ‘the Vigil of St Matthew the Apostle’ (20 September), then a few days later Harold Godwineson’s triumphant defeat of the Norwegian king at Stamford Bridge. Here the entry breaks off, and the Chronicle stops before reaching Hastings. For whatever reason, the chronicler was unable to write about that last autumn day.

When Christmas came that year, England had a new king, and would never be the same again. But Midwinter itself would have looked no different, and the cycle began another round. That last tumultuous year – in one sense, the last year of Anglo-Saxon history – was full of surprises and upheavals, yet the yearly cycle was stable and unchanging. And so it continued for many centuries.

(Parker 2022)

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

23 March 0867: Viking mercenaries draw the Anglo-Saxons of Ælla of Northumbria into the streets of York and slaughter them

23 March 0867: Viking mercenaries draw the Anglo-Saxons of Ælla of Northumbria into the streets of York and slaughter them 8 June 0793: Alcuin of York, a leading light of the Carolingian Renaissance, reflects in a poem on the devastation this day of Lindisfarne by Vikings

8 June 0793: Alcuin of York, a leading light of the Carolingian Renaissance, reflects in a poem on the devastation this day of Lindisfarne by Vikings 2 July 1644: Henry Slingsby of the Royalist York garrison recounts Prince Rupert’s defeat at Marston Moor today, which ends Charles I’s hopes in the north

2 July 1644: Henry Slingsby of the Royalist York garrison recounts Prince Rupert’s defeat at Marston Moor today, which ends Charles I’s hopes in the north 25 September 1880: Thomas Harper reveals to the Leeds Mercury’s young readers a mnemonic song of monarchs (except Oliver) used in the village school at Weldrake (York) in the 1770s

25 September 1880: Thomas Harper reveals to the Leeds Mercury’s young readers a mnemonic song of monarchs (except Oliver) used in the village school at Weldrake (York) in the 1770s

Comment

Comment

This image is preferable, but the BM’s lawyers are unlikely to drop their illegitimate copyright claims.

I guess George Speaight had a source for his description of Rowe’s puppet shows:

Rowe now heard that a widow, who was the proprietor of a puppet show, wanted an assistant to travel with it from town to town, and he obtained the position. He is said to have displayed great skill in manipulating the puppets, which were dressed in an expensive and elaborate style. On arriving at a town he would hire a large room in a well-to-do working-class district, and distribute a few hundred small handbills giving details of the programmes. At the door would be placed a large oil-lamp with two spouts, which gave a bright light as well as a most offensive smell, and the interior of the room would be lit by tin candlesticks, shaped to hang from nails in the wall. There would be candle footlights in front of the drop-curtain, and an orchestra of one or two violins. The programme usually consisted of a tragedy and farce, between which there would always be a short concert. Among his most popular songs were the sentimental “The Rose of Allendale” and a comic ballad known as “Chorus Tommy.” Ordinary performances took fully two hours, but at fairs the time was cut to twenty or thirty minutes; the whole show is said to have been very amusing, and to have made good use of local jokes. His mistress spoke for and worked the female puppets, he the male, and they did the entire show with one assistant. Before the performance Harry Rowe would stand outside inviting people in, and his mistress took the money; admission was a penny and threepence.

After a time they decided that it would be more profitable to work a regular circuit than to travel without any settled system, and they set upon York as their centre, visiting the surrounding market towns, such as Malton, Thirsk, and Tadcaster. The boxes of puppets were probably transported by carrier cart or perhaps pulled by a string of dogs. Harry Rowe eventually married the proprietress, and continued master of the puppets till his wife’s death in 1796. Shortly after this he sold the show, and retired to York. He is said to have made money easily during his career, but to have spent it freely, and in 1798 he entered the city workhouse, where he died in the next year at the age of seventy-four (Speaight 1955).

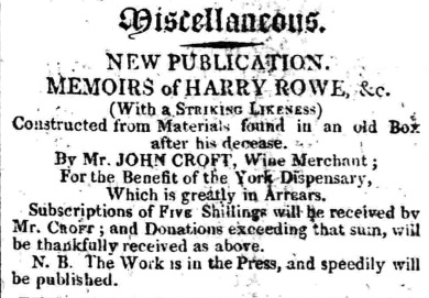

Speaight generously considers that there is some truth in the picaresque post-mortem “memoirs” attributed to John Croft (of which I suppose Rowe might have contributed top and tail) (Croft 1806). The rare book seller Bernard Quaritch provides a summary:

Apprenticed to a stocking-weaver, Rowe was dismissed for an ‘improper connexion with one of the maid servants’ and volunteered for the Duke of Kingston’s light horse in the year of the ’45 rebellion. He rose to the position of trumpeter, ‘behaved with great gallantry’ at Culloden, and when the unit was disbanded set off for London. Dismissed, for theft, from a position as ‘door-keeper and “groaner”’ to Orator Henley, he fell in with a crooked chemist (Van Gropen) and a quack (Dr. Wax – who reappears in ‘The Sham Doctor’) for whom he played the role of professional patient: ‘in the course of six months, he had been nine times cured of a dropsy’.

His next venture was a ‘wedding-shop’ in Coventry, a sort of matchmaking agency under the name of Thomas Tack. After ‘Mrs Tack’s’ death he quickly married the widow of a puppet-showman, and toured with her show all over the north, based at York, where he was also trumpeter to the High Sheriffs. During his life-time two dramatic works were published under his name: No Cure no Pay (1794) (see previous), and an edition of Macbeth (1797) interlarded with Shakespearean commentary by Rowe’s puppets, satirising the editions of Johnson, Steevens and Malone.

Much of the Memoirs (pp. 11-43) is taken up by cod letters written to Mr. Tack by singletons in search of a partner: a ‘giddy girl of sixteen’ seeks ‘a captain as soon as possible … for at present I lead a life no better than my aunt’s squirrel’; Dorothy Grizzle complains that the sea captain she was matched with has false eyebrows, false teeth, a glass eye, a wooden arm and a cork leg; the lady of Bondfield manor writes claiming droit du seigneur over all his matches, etc.

The Memoirs were published in aid of the York Dispensary, where Dr. Alexander Hunter (d.1809) had been physician since it began in 1788 (Bernard Quaritch 2021).

The ad in the York Herald, July 5, 1806, suggests that all was not well with Dr. Hunter:

While in the York Herald, November 15, 1806, Croft was helping Mrs. Rowe, despite, pace Speaight, her having died ten years before:

Mr. John Croft has given this week part of the produce of the subscription, arising from the Memoirs of Harry Rowe, to his widow, Mrs. Rowe, who is an object of great charity, being stone blind.

Not even Speaight seems to think that Rowe edited Macbeth, e.g. “If we mistake not, however, this was in reality the work of an eminent physician at York” (European Magazine 1800) – Dr. Alexander Hunter, editor of Evelyn, and physician at the York Dispensary from its foundation in 1788. However, a comparison of its style and that of the biographical intro credited (perhaps accurately, given the earlier, perhaps pre-senescence, date) to Rowe for wine merchant John Croft’s Select collection of the beauties of Shakspeare (Shakespeare 1792) suggests to me that the emendations to Macbeth may actually have been the work of Rowe.

More of the Macbeth preface, attributed to Rowe, and dated 30 May 1799:

I have the vanity to say, that for these thirty years past, I have honourably filled the office of trumpet-major to the high sheriffs of Yorkshire; and during that long period, I have ushered into the castle of York no less than ninety judges, all learned in the law. Yet, notwithstanding the emoluments of my high office, I was, six months ago, as poor as the poorest felon that ever was hanged at Tyburn; and, had it not been for the kind interference of a few friends, I must have died of want, in which case, the world would have lost an able commentator, and my benefactors a grateful friend. Critics may call me an impudent fellow, if they please, and my associates a parcel of blockheads; but I would have those learned gentlemen to know, that what we want in genius, we make up in solidity (Shakespeare 1799).

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter