3 May 1343: Short of cash for his French wars, Edward III asks what the effect on his rental income will be of January storms and coastal erosion at Ravenser Odd (Holderness)

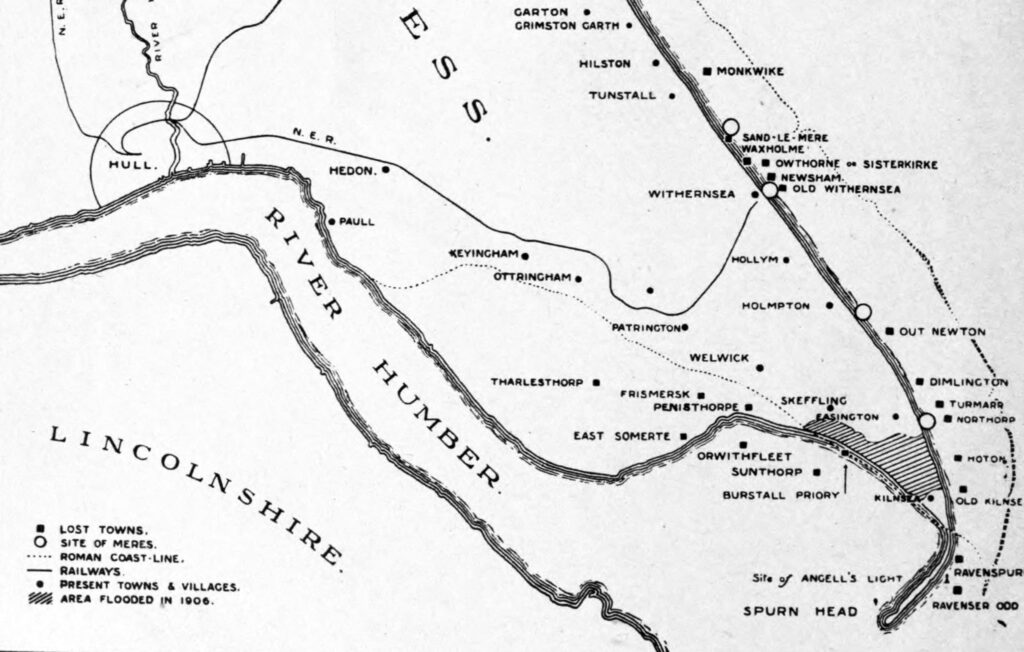

Towns past and present on the East Yorkshire coast on the eve of World War I (Sheppard 1912).

HMG. 1902. Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, Vol. 12, Edward III (1343-45). London: HMSO. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

1343. May 3. Westminster. Commission to Philip de Weston, Michael de Wath, John de Mounceaux and John de Ludyngton to make inquisition by the oath of good men of the county of York and certify the king whether it is true that many houses built on his places in his town of Ravenserod and let to farm have been lately thrown down and washed away by the sea, that the places are so inundated by the sea that the tenants can make no profit therefrom and will not be able to pay the rents due to him and that the men still dwelling in the town will not be able to save the houses there or any part of the town from the sea unless he help them with timber and other charges, and if so whether it will be possible by making wooden quays or other defence to save the remaining houses and what the probable cost will be, and whether his tenants there will be equal to the charges without aid from him. By K.

Comment

Comment

The fiscal fatigue caused by the Hundred Years’ War was a cause of the 1343-45 Truce of Malestroit.

Thomas Sheppard is a good starting point for respectively Ravenser and Ravenser Odd:

William Shelford … points out that Spurn Point, even in Roman times, must have been 2,250 yards at least beyond the present coastline ; and that at or near this spot the Danes landed in 867, planted their standard “The Raven,” and practically originated the town of Ravensburg, or Ravenser, or Ravenseret, within Spurn Head. The town developed into “one of the most wealthy and flourishing ports of the kingdom. It returned two Members to Parliament, assisted in equipping the navy, had an annual fair of thirty days, two markets a week, is mentioned twice by Shakespeare,[King Henry VI, part iii, Act iv, Scene 7; and Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1] and considered itself honoured by the embarkation of Baliol with his army for the invasion of Scotland in 1332; by the landing of Bolingbroke, afterwards Henry IV, in 1399; and by the landing of Edward IV in 1471, not long after which it was entirely swept away.” Today, we cannot even be certain where the place was. […] In 1296 “Kaiage” [right to tax wharf occupation] was granted to the inhabitants by Edward I. Two years later Ravenser petitioned the king for certain privileges, and offered 300 marks in payment. In 1300 the magistrates of Ravensere were enjoined to stop the export of bullion; in 1305 it sent Members to Parliament. In 1310 Ravensere remonstrated against the depredations of the Earl of Holland, and in the same year Ravenness sent ships for Edward II.’s expedition to Scotland. Two years later the inhabitants were empowered to levy a tax to defend their walls. In 1323 commissions were issued for the “Wapentak of Ravensere.” In 1335-6 warships of Ravensere are referred to, and in 1341 Ravensere sent one Member to “a sort of” naval Parliament of Edward III. In 1346 one ship only was sent by Ravenser to the siege of Calais; (Hull sent 16). In 1355 bodies were washed out of their graves in the chapelyard at Ravenser. In 1361 [i.e. 1362 – the Second St. Marcellus flood] the floods drove the merchants to Hull and Grimsby; and by 1390 nearly all trace of the town, as such, was gone.* In 1413 a grant was made for the erection of a hermitage at Ravenscrosbourne, and in 1428 Richard Reedbarowe, the hermit of the chapel of Ravensersporne obtained a grant to take tolls of ships for the completion of his light-tower. In 1538 Leland refers to Ravenspur in his ” Itinerary,” which seems to be the last reference to the place. As pointed out elsewhere, the place is not included in Holinshed’s ” List of Ports and Creeks,” which was issued before 1580.

[…]

Ravenser-odd (also referred to as Odd near Ravenser, Ravenserot, Ravensrood, Ravensrodd, Ravensrode, etc.), probably originated in the early part of the thirteenth century, soon after Ravenser, the adjoining port, came to be of importance. Ravenser-odd was apparently built on an island.

In 1251 some monks obtained half an acre of ground on which to erect buildings for the preservation of fish, in the burg of Od near Ravenser. The chronicler of Meaux wrote that “Od was in the parish of Esington, about a mile distant from the mainland. The access to it was from Ravenser by a sandy road covered with round yellow stones, scarcely elevated above the sea. By the flowing of the ocean it was little affected on the east, and on the west it resisted in a wonderful manner the flux of the Humber.”

In 1273 there was a dispute about a chapel at Od, and this was carried on for some time.

In 1300 Edward I. gave some lands in Ravenserodde to the convent of Thornton in Lincolnshire, and others to St. Leonard’s Hospital, York.

In 1315 the burgesses of Ravenserod agreed to pay the king £50 for the confirmation of their charters, and “Kaiage” for seven years. In 1326 the king granted dues and customs in the port of Ravenserod, and about 1336 William De-la-Pole left Ravenserod for Hull. Ravenserode sent a representative to Edward III.’s “naval Parliament” in 1344, as well as a man well versed in naval affairs.

In 1346 Ravensrodde was one of the places mentioned by the Abbot of Meaux as suffering by the sea. In the following year it was frequently inundated, and in 1360 [presumably 1362] “Ravenser Odd was totally annihilated by the floods of the Humber and inundations of the great sea.”

In 1355 the bodies in the chapel yard, which, “by reason of inundations were then washed up and uncovered,” were removed and buried in the churchyard at Easington.

About this time we read the following curious note in the Meaux Chronicle : — ” When the inundations of the sea and of the Humber had destroyed to the foundations the chapel of Ravenserre Odd, built in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so that the corpses and bones of the dead there buried horribly appeared, and the same inundations daily threatened the destruction of the said town, sacrilegious persons carried off and alienated certain ornaments of the said chapel, without our due consent, and disposed of them for their own pleasure ; except a few ornaments, images, books, and a bell which we sold to the mother church of Esyngton, and two smaller bells to the church of Aldeburghe. But that town of Ravenserre Odd, in the parish of the said church of Esyngton, was an exceedingly famous borough, devoted to merchandise, as well as many fisheries, most abundantly furnished with ships and burgesses amongst the boroughs of that sea-coast. But yet, with all inferior places, and chiefly by wrong-doing on the sea, by its wicked works and piracies, it provoketh the wrath of God against itself beyond measure. Wherefore, within the few following years, the said town, by those inundations of the sea and of the Humber, was destroyed to the foundations, so that nothing of value was left.”

Notwithstanding this, “In the Hedon inquisition of January 1401, the chapel of Ravenserodde, with the town itself, was declared to be worth, in spiritualities, more than £30 per annum.”

William Wheater treads a similar path, perhaps better – haven’t read it (Wheater 1889).

The rise and fall of a tsunami are among the 15 signs of doom in a Middle English poem, The Pricke of Conscience, and are illustrated in a medieval (ca. 1410) window in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York:

Þe first day of þas fiften days,

Þe se sal ryse, als þe bukes says,

Abowen þe heght of ilka mountayne,

Fully fourty cubyttes certayne,

And in his stede even upstande,

Als an heghe hille dus on þe lande.

Þe secunde day, þe se sal be swa law

Þat unnethes men sal it knaw.

Þe thred day, þe se sal seme playn

And stand even in his cours agay[n],

Als it stode first at þe bygynnyng,

With-outen mare rysyng or fallyng

(Anon 1863)

Britta Sweers, “Trutz, Blanke Hans” – Musical and Sound Recollections of North Sea Storm Tides in Northern Germany

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington

1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington 18 January 1966: Barbara Castle (Lab.) swings the Hull North by-election with a bridge over the Humber, convincing Harold Wilson that he has the momentum to win a general election

18 January 1966: Barbara Castle (Lab.) swings the Hull North by-election with a bridge over the Humber, convincing Harold Wilson that he has the momentum to win a general election

Comment

Comment

Rymer’s Foedera indicates that detailed implementation was ordered on 21 September 1335:

The bailiffs of Great Yarmouth and 18 other ports are ordered to proclaim that no person leaving the country is to exchange money except at the appointed tables of exchange. Edinburgh. E. ii p. ii. 922. 0. iv. 668. H. ii. p. iii. 135. (Rymer 1869)

The scheme was entrusted to the sticky fingers of William de la Pole of Hull:

From 1335 de la Pole would also need a headquarters in London for his new appointment as Warden of the Exchanges. Under the Statute of Money made that year at York, the King was empowered to ordain tables of Exchange to be set up from time to time in seaport towns. By September 1335, tables had already been instituted at London, Dover, Great Yarmouth, Boston and Kingston upon Hull, and William was made responsible for the issues of these exchanges, As head Warden he could appoint his deputies in the ports, but the King, as a safeguard, appointed the local controllers. It was now illegal for merchants, pilgrims and others to take ourrency or plate out of the realm or to exohange their money exoept at the appointed places, and the bailiffs of Hull and other principal cities and towns were notified of William’ s appointment. De la Pole’s account of the “Profit of Exchange” at the five ports for the half-year ended March 1336 is given in the Wardrobe Acoounts. The profit account shows that the principal ports actually used for Exchange purposes were Dover and Great Yarmouth. De la Pole was removed from his office at the end of his half-year, when he was advised that “it will not behove him to intermeddle further.” (Harvey 1957)

The reign of Edward III may be taken as the time when an indigenous gold coinage became an important part of the currency of the realm. The change was due mainly to the foreign relations of England — both political and commercial — in this reign, but partly also to the difficulties caused by the constant influx of debased silver coins from the Continent, In 1337, when the Hundred Years’ War began, Edward entered into alliance with the German princes and was made VicarGeneral of the Emperor with power to coin both gold and silver, though it is not at all likely that the English king recognized the necessity for the imperial sanction in this respect. Just at this time a large quantity of base money was coming into the country through the trade with Flanders ; it was struck in a white metal resembling silver, and was so inferior in quality that coins to the nominal value of a pound were sometimes worth no more than 40 pence. This influx of base money had caused such a dearth of good money that the Government found it necessary as early as 1335 to try and check the evil by legislation (Dodd 1911)

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter