7 June 1703: A list of shares in ship-owning partnerships held by Samuel Pinder of Whitby on this date

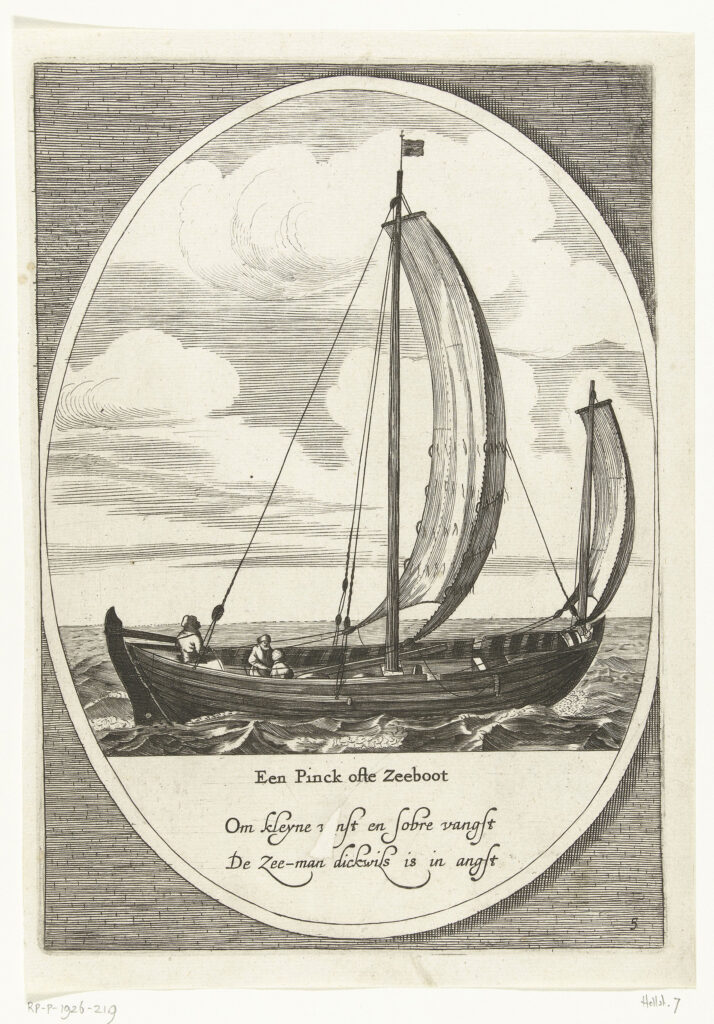

Dirk Eversen Lons’s 1642 print of a fisher’s pink, from his series of ten types of Dutch inland ships. The verse, “Om kleyne winst en sobre vangst / De zeeman dickwils is in angst,” could be translated as “For modest catch and meagre gain / The seaman oftentimes fears pain” (Lons 1642).

George Young. 1817. A History of Whitby, and Streoneshalh Abbey, Vol. 2. Whitby: Clark and Medd. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

In an inventory of the goods of Samuel Pinder … taken June 7th, 1703, are these items: “In shipping. In his own vessel, six 16ths, ⅓, one 64th part – £160. In one 32th of William Johnson vessel – £30. In one 32th of Stephen Russell pinque – £13. In one 32th Richard Chapman pinque – £7 10s. In one 32th Ebo. Marshall ship – £20. In one 32th Henry Pearson ship – £20. In one 32th William Fotherley ship – £20. In one 32th Geo. Jackson vessel – £6. In one 32th Fra. Barker pinque £12 10s.”

Comment

Comment

Young writes that vessels owned and exploited in this fashion were called club ships – OED take note! – and that “almost all our all our present Greenland ships are also held in shares, but not in such small shares as 32ds and 64ths.” For a full account, see Ralph Davis’ chapter on “The shipowners” (Davis 2017).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

27 June 1743: Tom Brown of Kirkleatham’s heroics against the French today at Dettingen (Bavaria) lead his general, George II, to grant him a silver prosthetic nose, immortalised in ballad and portrait

27 June 1743: Tom Brown of Kirkleatham’s heroics against the French today at Dettingen (Bavaria) lead his general, George II, to grant him a silver prosthetic nose, immortalised in ballad and portrait

Comment

Comment

Orderic Vitalis:

In the month of August, Harold, king of Norway, and Tostig, with a powerful fleet set sail over the wide sea, and, steering for England with a favourable aparctic, or north wind, landed in Yorkshire, which was the first object of their invasion. Meanwhile, Harold of England, having intelligence of the descent of the Norwegians, withdrew his ships and troops from Hastings and Pevensey, and the other seaports on the coast lying opposite to Neustria, which he had carefully guarded with a powerful armament during the whole of the year, and threw himself unexpectedly, with a strong force by hasty marches on his enemies from the north. A hard-fought battle ensued, in which there was great effusion of blood on both sides, vast numbers being slain with brutal rage. At last the furious attacks of the English secured them the victory, and the king of Norway as well as Tostig, with their whole army, were slain. The field of battle may be easily discovered by travellers, as great heaps of the bones of the slain lie there to this day, memorials of the prodigious numbers which fell on both sides.

While however the attention of the English was diverted by the invasion of Yorkshire, and by God’s permission they neglected, as I have already mentioned, to guard the coast, the Norman fleet, which for a whole month had been waiting for a south wind in the mouth of the river Dive and the neighbouring harbours, took advantage of a favourable breeze from the west to gain the roads of St. Valeri. While it lay there innumerable vows and prayers were offered for the safety of themselves and their friends, and floods of tears were shed. For the intimate friends and relations of those who were to remain at home, witnessing the embarkation of fifty thousand knights and men-at-arms, with a large body of infantry, who had to brave the dangers of the sea, and to attack an unknown people on their own soil, were moved to tears and sighs, and full of anxiety both for themselves and their countrymen, their minds fluctuating between fear and hope. Duke William and the whole army committed themselves to God’s protection, with prayers, and offerings, and vows, and accompanied a procession from the church, carrying the relics of St. Valeri, confessor of Christ, to obtain a favourable wind. At last when by God’s grace it suddenly came round to the quarter which was the object of so many prayers, the duke, full of ardour, lost no time in embarking the troops, and giving the signal for hastening the departure of the fleet. The Norman expedition, therefore, crossed the sea on the night of the third of the calends of October [29th September], which the Catholic church observes as the feast of St. Michael the archangel, and, meeting with no resistance, and landing safely on the coast of England, took possession of Pevensey and Hastings, the defence of which was entrusted to a chosen body of soldiers, to cover a retreat and guard the fleet.

Meanwhile the English usurper, after having put to the sword his brother Tostig, and his royal enemy, and slaughtered their immense army, returned in triumph to London. As however worldly prosperity soon vanishes like smoke before the wind, Harold’s rejoicings for his bloody victory were soon darkened by the threatening clouds of a still heavier storm. Nor was he suffered long to enjoy the security procured by his brother’s death; for a hasty messenger brought him the intelligence that the Normans had embarked (Ordericus Vitalis 1853).

I rather like Eleanor Parker’s summing up of the end of the C text of the Chronicle:

The last entry in this version of the Chronicle is for 1066, and it contains a memorable cluster of significant events dated to points in the festival year. From Edward the Confessor, spending Christmas in Westminster at ‘Midwinter’ but dead and buried by ‘Twelfth Day’, the year runs through moments of political crisis dated to Easter, harvest and the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, as Harold Godwineson first gained, then fought to keep, the English crown. The last events recorded are a battle in Yorkshire between an English army and the forces of the Norwegian invader, Harald Hardrada, on ‘the Vigil of St Matthew the Apostle’ (20 September), then a few days later Harold Godwineson’s triumphant defeat of the Norwegian king at Stamford Bridge. Here the entry breaks off, and the Chronicle stops before reaching Hastings. For whatever reason, the chronicler was unable to write about that last autumn day.

When Christmas came that year, England had a new king, and would never be the same again. But Midwinter itself would have looked no different, and the cycle began another round. That last tumultuous year – in one sense, the last year of Anglo-Saxon history – was full of surprises and upheavals, yet the yearly cycle was stable and unchanging. And so it continued for many centuries.

(Parker 2022)

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter