14 April 1843: John Nicholson, “the Airedale Poet,” “the Bingley Baron,” dies after falling into the Aire while drunk

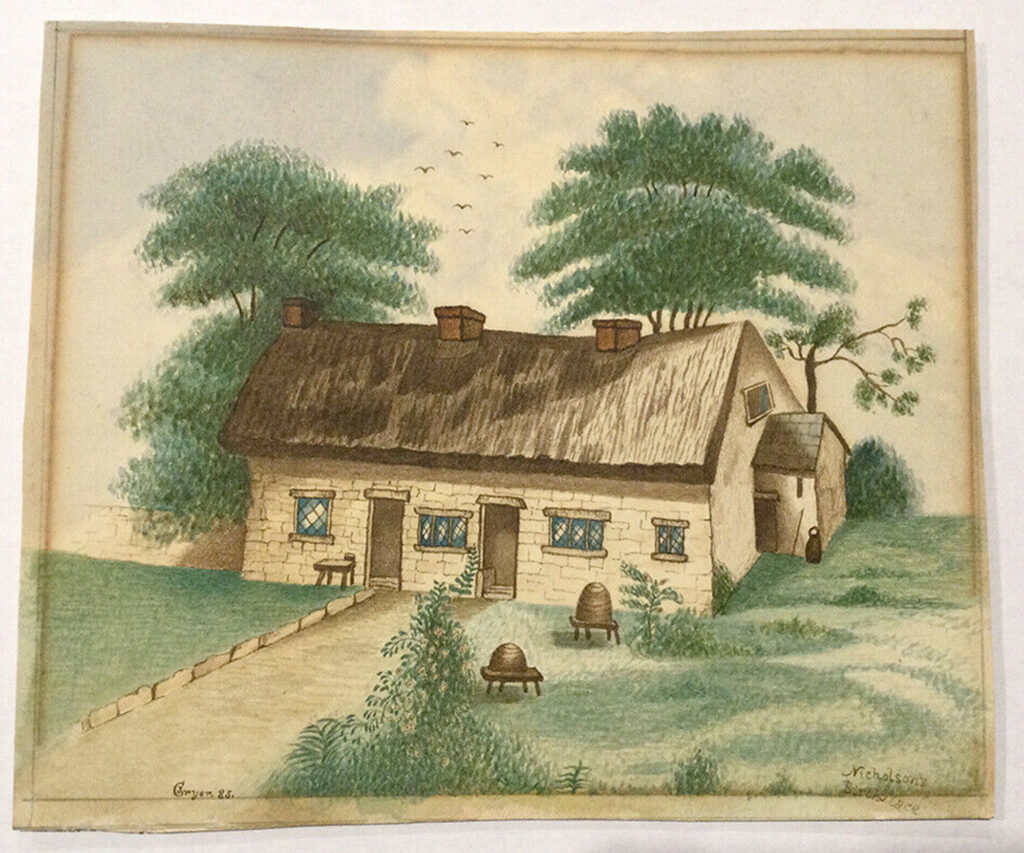

A naive watercolour on the title-page to John Nicholson’s poems, showing his birthplace – a rural thatched cottage, with beehives in the front garden (Cryer 1885).

John Nicholson. 1876. The Poetical Works of John Nicholson (The Airedale Poet). Ed. W.G. Hird. London/Bradford: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co./Thomas Brear. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

The closing period of Nicholson’s life was an alternate struggle between labour and dissipation. His early religious impressions and convictions were strong in his sober moments, and on Sundays he delighted to read to his family the poetical books of Scripture, and point out the sublimest passages. He was one of the first employed by Sir Titus Salt, Bart., in sorting alpaca and mohair, which are now so largely used in our textile manufactures. Full of good resolves in his thoughtful hours, when suffering from the effects of drinking, he often earnestly determined upon amendment one day, and the next fell again into dissipation. This irregular course of life unfitted him for mental pursuits, and blunted his powers of poetical conception, so that he wrote little towards the end of his life worthy of being preserved. Still at times he felt a consciousness of being able to achieve greater poetic fame by trying loftier themes, but allowed them to remain in embryo. His love of the wild scenery around Eldwick grew with years, and rambles on the moorland or the shady dells in the neighbourhood afforded him the highest gratification during his holidays. The charms of the country exceeded those of the town at such times, and he used to say, “I’ll be off to Eldwick to breathe a little mountain air, and get my throat cleansed from the smoke of Bradford,” and generally started the night before the holiday. Accordingly he left home the evening before Good Friday, April 13th, 1843, to visit his aunt, and called at several places on the way. Towards midnight he was seen going up the canal bank in the direction of Dixon Mill, where the Aire was crossed by means of stepping stones. “The night was dark and stormy, and the river swollen.” He appears to have missed his footing when nearly across, fell into the deep part of the current, and was carried down eight or ten yards, when he caught hold of some hazel boughs, and by great exertion struggled out of the water. He afterwards crept through a hole in the hedge which fences off the river, and lay down benumbed and exhausted till about six o’clock next morning, when a half-witted person as he was passing heard him groan, and saw him rise into a sitting posture. The man was alarmed and rendered no assistance, but hastened to the farm-house where he was going for milk, said nothing, and returned home another way. Two hours later he was found by a farm labourer, who called out, but on receiving no answer, ran to inform his master at Baildon, who immediately returned with him to the place, where they found poor Nicholson quite dead, but still warm. The body was removed to the Bay Horse Inn, Baildon, where a medical man was soon in attendance and attributed his death to apoplexy caused by exposure to the cold after having been in the water. The coroner, at the inquest, recorded a verdict in agreement with the medical testimony; and on Tuesday, April 18th, Nicholson’s remains were interred in Bingley Churchyard, in the presence of more than a thousand spectators. A muffled peal was rung on the bells, and a full choir took part in the burial service. A neat tombstone was raised over his grave by the widow, with the kind assistance of George Lane Fox, Esq., shortly afterwards.

Comment

Comment

Nicholson was something of an anti-poster boy for the Yorkshire temperance movement:

John Nicholson (the Airedale poet) was for some time one of the active members of the Wilsden Temperance Society, and signed the pledge at a meeting held in the Independent Chapel, February 14th, 1835. He said “he had been one of the most dreadful characters, and that perhaps he had drunk more liquor than any person present.” He earnestly sought for the prayers of the audience that he would be able to remain steadfast to the pledge. During his connection with the society he wrote Genius and Intemperance, and some of his finest poems and songs; but alas! his own poor faith failed him, the drink craving was too firmly planted in his system, and the temptations to which he was exposed stronger than he could bear, and he fell into the vortex (Winskill 1891).

[

“Vortex” is used here both figuratively, which is to say morally, and in the nowadays uncommon literal sense of “a whirl or swirling mass of water; a strong eddy or whirlpool” (OED):

Had Dr. Slop beheld Obadiah a mile off, posting in a narrow lane directly towards him, at that monstrous rate,—splashing and plunging like a devil thro’ thick and thin, as he approached, would not such a phænomenon, with such a vortex of mud and water moving along with it, round its axis,—have been a subject of juster apprehension to Dr. Slop in his situation, than the worst of Whiston’s comets?—To say nothing of the NUCLEUS; that is, of Obadiah and the coach-horse.—In my idea, the vortex alone of ’em was enough to have involved and carried, if not the doctor, at least the doctor’s pony, quite away with it (Sterne 1792).

]

There is something of poetic justice in Nicholson’s fate, given his treatment of the ladies in “Airedale in ancient times”:

Then on the green the nymphs and swains would dance,

Or, in a circle, tell some old romance;

And all the group would seriously incline

To hear of Saracens and Palestine,-

Of knights in armour of each various hue,

Of ladies left, some false, and others true.

Their pure descriptions showed how warriors bled,

How virgins wept to hear of heroes dead-

The furious steeds swift rushing to the war,

The turbann’d Turks, the bloody scimitar,-

The cross-marked banners on the lofty height,

The impious struck with terror at the sight!

Then told what spectres grim were seen to glide

Along this dale, before its heroes died,

Then marked their fall within the holy vale,

Described them, lifeless, in their coats of mail,-

Told how some lady, frantic with despair,

Shriek’d, as she plung’d into the deeps of Aire,

When tidings reach’d her from the Holy Land,

That her lov’d lord lay deep in Jordan’s sand-

And how her shrieks flew echoing through the wood,

While her rich jewels glittered in the flood!

(Nicholson 1876)

But I rather like some of his stuff, though I’d also like to read Tony Harrison’s Poetry or bust.

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

30 May 1835: Alfred Austin, future poet laureate, “Banjo-Byron that twangs the strum-strum,” is born into rural splendour at Ashwood, 48 Headingley Lane, Leeds

30 May 1835: Alfred Austin, future poet laureate, “Banjo-Byron that twangs the strum-strum,” is born into rural splendour at Ashwood, 48 Headingley Lane, Leeds

Comment

Comment

Water Lane used to extend from Bridge Road in Holbeck past the Victoria Bridge to Leeds Bridge, but much of the eastern part is now submerged under the dismal Asda House.

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter