4 July 1858: Incipient water-baby Tom arrives at Malham Cove, discovered today by Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley. 1889. The Water-babies. London: Macmillan and Co. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

At last, at the bottom of a hill, they came to a spring; not such a spring as you see here, which soaks up out of a white gravel in the bog, among red fly-catchers, and pink bottle-heath, and sweet white orchis; nor such a one as you may see, too, here, which bubbles up under the warm sandbank in the hollow lane by the great tuft of lady ferns, and makes the sand dance reels at the bottom, day and night, all the year round; not such a spring as either of those; but a real North country limestone fountain, like one of those in Sicily or Greece, where the old heathen fancied the nymphs sat cooling themselves the hot summer’s day, while the shepherds peeped at them from behind the bushes. Out of a low cave of rock, at the foot of a limestone crag, the great fountain rose, quelling, and bubbling, and gurgling, so clear that you could not tell where the water ended and the air began; and ran away under the road, a stream large enough to turn a mill; among blue geranium, and golden globe-flower, and wild raspberry, and the bird-cherry with its tassels of snow.

And there Grimes stopped, and looked; and Tom looked too. Tom was wondering whether anything lived in that dark cave, and came out at night to fly in the meadows. But Grimes was not wondering at all. Without a word, he got off his donkey, and clambered over the low road wall, and knelt down, and began dipping his ugly head into the spring—and very dirty he made it.

Tom was picking the flowers as fast as he could. The Irishwoman helped him, and showed him how to tie them up; and a very pretty nosegay they had made between them. But when he saw Grimes actually wash, he stopped, quite astonished; and when Grimes had finished, and began shaking his ears to dry them, he said:

“Why, master, I never saw you do that before.”

“Nor will again, most likely. ’Twasn’t for cleanliness I did it, but for coolness. I’d be ashamed to want washing every week or so, like any smutty collier lad.”

“I wish I might go and dip my head in,” said poor little Tom. “It must be as good as putting it under the town-pump; and there is no beadle here to drive a chap away.”

“Thou come along,” said Grimes; “what dost want with washing thyself? Thou did not drink half a gallon of beer last night, like me.”

“I don’t care for you,” said naughty Tom, and ran down to the stream, and began washing his face.

Grimes was very sulky, because the woman preferred Tom’s company to his; so he dashed at him with horrid words, and tore him up from his knees, and began beating him. But Tom was accustomed to that, and got his head safe between Mr. Grimes’ legs, and kicked his shins with all his might.

“Are you not ashamed of yourself, Thomas Grimes?” cried the Irishwoman over the wall.

Grimes looked up, startled at her knowing his name; but all he answered was, “No, nor never was yet;” and went on beating Tom.

“True for you. If you ever had been ashamed of yourself, you would have gone over into Vendale long ago.”

“What do you know about Vendale?” shouted Grimes; but he left off beating Tom.

“I know about Vendale, and about you, too. I know, for instance, what happened in Aldermire Copse, by night, two years ago come Martinmas.”

“You do?” shouted Grimes; and leaving Tom, he climbed up over the wall, and faced the woman. Tom thought he was going to strike her; but she looked him too full and fierce in the face for that.

“Yes; I was there,” said the Irishwoman quietly.

“You are no Irishwoman, by your speech,” said Grimes, after many bad words.

“Never mind who I am. I saw what I saw; and if you strike that boy again, I can tell what I know.”

Grimes seemed quite cowed, and got on his donkey without another word.

“Stop!” said the Irishwoman. “I have one more word for you both; for you will both see me again before all is over. Those that wish to be clean, clean they will be; and those that wish to be foul, foul they will be. Remember.”

Comment

Comment

A letter written Tuesday 6 July 1858 describes the real-life events of Sunday 4:

“Here I am still (after having been to church at Horton in Ribblesdale). All that I have heard of the grandeur of Godale Scar and Malham Cove, was, I found, not exaggerated. The awful cliff filling up the valley with a sheer cross wall of 280 feet, and from beneath a black lip at the foot, the whole river Air coming up, clear as crystal, from unknown abysses. Its real source is, I suppose, in the great lake above, Malham Tarn, on which I am going to-morrow. The fishing is the best in the whole earth. Last night we went up Ingleborough, 2380, and saw the whole world to the west, the lake mountains, and the western sea beyond Lancaster and Morecambe Bay for miles. There was a cap on Scawfell forty miles away which has ended in heavy rain to-day. The people are the finest I ever saw-tall, noble, laconic, often very handsome. Very musical too, the women with the sweetest voices in speech which I have ever heard. I trust Rose has got her letter; I sent it down to Settle by a man (Kingsley 1878).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

13 October 1769: The poet Thomas Gray walks from Malham (“Maum”) to Gordale Scar and is horrified at the sight

13 October 1769: The poet Thomas Gray walks from Malham (“Maum”) to Gordale Scar and is horrified at the sight 19 October 1816: Serenaded by the military, decorated barges leave Leeds for Liverpool to celebrate the completion, after almost 50 years, of the canal uniting east and west

19 October 1816: Serenaded by the military, decorated barges leave Leeds for Liverpool to celebrate the completion, after almost 50 years, of the canal uniting east and west 23 January 1643: Thomas Fairfax, the Rider of the White Horse, captures Leeds from the Beast with the help of Psalm 68

23 January 1643: Thomas Fairfax, the Rider of the White Horse, captures Leeds from the Beast with the help of Psalm 68 12 December 1641: John Sugden causes panic in Bradford and Pudsey with news of the imminent advent of genocidal Irish Catholics

12 December 1641: John Sugden causes panic in Bradford and Pudsey with news of the imminent advent of genocidal Irish Catholics

Comment

Comment

Did Grassington have any kind of representative body? What happened to the group photo referred to at the end? Nine men in August 1874 Grassington should be findable!

Re dialect almanacs:

A Poor Rabbin’s Ollminick appeared in Belfast in 1861. It was written in dialect, and its purpose was not comic but to record that dialect for antiquarian purposes. Writes Maureen Perkins, historian of nineteenth-century almanacs, ‘The memory of Poor Robin was alive, but somewhat altered in the recalling.’

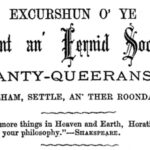

Poor Robin’s special humour of the wise fool who knows better than his betters did resurface, though, in a remarkable flourishing of almanacs written in regional dialect which took place in the north-east of England, in Yorkshire and Lancashire, from the 1840s.

This flourishing of creativity among self-taught manual workers generated such titles as the Bairnsla Foaks’ Annual, the Nidderdill Olminac and the Shevvild Chap’s Almanac. By 1877 there were about forty different titles and one—the Original Halifax Illuminated Clock Almenack—would continue until 1956.

These almanacs preserved both the form and the function of Old Poor Robin—some of them matched its physical form quite closely—celebrating local events and regional pride. Some, like the Bairnsla Foaks’ Annual, also contained some mocking judicial astrology. The Bairnsla, known as ‘the Punch of the North’, came to resemble Old Poor Robin very markedly in some of its humorous predictions:

Widows will roar for the loss of their husbands, owd Maids will sigh for’t’want a wun.

Evidently Poor Robin’s brand of humour retained its vitality even after his demise.

(Wardhaugh 2012)

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter