5 July 1858: The view from the tower of Beverley Minster

Walter White. 1861. A Month in Yorkshire, 4th Ed. London: Chapman and Hall. The best of White’s travel writing, in which, as usual, he encounters and investigates the Plain People. This is the golden age of walking, when there were good roads pretty much everywhere, and they hadn’t yet been made inaccessible to pedestrians by cars. His July is told in 31 chapters, which seem to refer to the days of the month. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

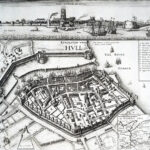

“On my first coming to England I landed at Hull, whose scenery enraptured me. The extended flatness of surface—the tall trees loaded with foliage—the large fat cattle wading to the knees in rich pasture—all had the appearance of fairy-land fertility. I hastened to the top of the first steeple—thence to the summit of Beverley Minster, and wondered over the plain of verdure and rank luxury, without a heathy hill or barren rock, which lay before me. When, after being duly sated into dullness by the constant sight of this miserably flat country, I saw my old bare mountains again, my ravished mind struggled as if it would break through the prison of the body, and soar with the eagle to the summit of the Grampians. The Pentland, Lomond, and Ochil hills seemed to have grown to an amazing size in my absence, and I remarked several peculiarities about them which I had never observed before.”

This passage occurs in the writings of the late James Gilchrist, an author to whom I am indebted for some part of my mental culture. I quote it as an example of the different mood of mind in which the view from the top of the tower may be regarded. To one fresh from a town it is delightful. As you step on the leads and gaze around on what was once called “the Lowths,” you are surprised by the apparently boundless expanse—a great champaign of verdure, far as eye can reach, except where, in the north-west, the wolds begin to upheave their purple undulations. The distance is forest-like: nearer the woods stand out as groves, belts, and clumps, with park-like openings between, and everywhere fields and hedgerows innumerable. How your eye feasts on the uninterrupted greenness, and follows the gleaming lines of road running off in all directions, and comes back at last to survey the town at the foot of the tower!

Few towns will bear inspection from above so well as Beverley. It is well built, and is as clean in the rear of the houses as in the streets. Looking from such a height, the yards and gardens appear diminished, and the trim flower-beds, and leafy arbours, and pebbled paths, and angular plots, and a prevailing neatness reveal much in favour of the domestic virtues of the inhabitants. And the effect is heightened by the green spaces among the bright red roofs, and woods which straggle in patches into the town, whereby it retains somewhat of the sylvan aspect for which it was in former times especially remarkable.

Comment

Comment

Chapter 5 of the 31 of White’s month of July, so perhaps the 5th.

In many words we change ol and owl into au; as for cold they say caud; for old, aud; thence Audley, as much as to say Old Town; for Elder, Auder; or as we write Alder; thence Alderman, a Senator; for Wolds or Woulds, Wauds; thus the ridge of hills in the east, and part of the North Riding of Yorkshire (our Apennine), is called: and sometimes the country adjoining is called the Wauds. But that which lies under the hills, especially down by Humber and Ouse side, towards Howden, is called by the country people the Lowths, i.e. the low country, in contradistinction to the Wauds. Though some call all the East Riding besides Holderness, and in distinction from it, the Woulds (Ray 1691).

The James Gilchrist quote is from his Intellectual patrimony (Gilchrist 1817).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington

1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington 18 January 1966: Barbara Castle (Lab.) swings the Hull North by-election with a bridge over the Humber, convincing Harold Wilson that he has the momentum to win a general election

18 January 1966: Barbara Castle (Lab.) swings the Hull North by-election with a bridge over the Humber, convincing Harold Wilson that he has the momentum to win a general election 24 August 1921: The British-built United States Navy R.38 airship collapses, explodes, and crashes into the Humber at Hull, killing 44 of the 49 crew

24 August 1921: The British-built United States Navy R.38 airship collapses, explodes, and crashes into the Humber at Hull, killing 44 of the 49 crew

Comment

Comment

Smeaton’s scheme did not prosper. John Timperley:

Various schemes had been suggested for cleansing the dock of the mud brought in by the tide; one was by making reservoirs in the fortifications or old town ditches, with the requisite sluices, by means of which the mud was to be scoured out at low water; another by cutting a canal to the Humber, from the west end of the dock, where sluices had been provided, and put down for the purpose, when it was proposed to divert the ebb tide from the river Hull along the dock, and through the sluices and canal into the Humber, and so produce a current sufficient, with a little manual assistance, to carry away the mud. Both of these schemes were however abandoned, and the plan of a horse dredging machine adopted; this work began about four years after the Old dock was completed, and continued until after the opening of the Junction dock. The machine was contained in a square and flat bottomed vessel 61 feet 6 inches long, 22 feet 6 inches wide, and drawing 4 feet water: it at first had only eleven buckets, calculated to work in 14 feet water, in which state it remained till 1814, when two buckets were added so as to work in 17 feet water, and in 1827 a further addition of four buckets was made, giving seventeen altogether, which enabled it to work in the highest spring tides. The machine was attended by three men, and worked by two horses, which did it at first with ease, but since the addition of the last four buckets, the work has been exceedingly hard.

There were generally six mud boats employed in this dock before the Humber dock was made; since which there have been only four, containing, when fully laden, about 180 tons, and usually filled in about six or seven hours; they are then taken down the old harbour and discharged in the Humber at about a hundred fathoms beyond low water mark, after which they are brought back into the dock, sometimes in three or four hours, but generally more. The mud engine has been usually employed seven or eight months in the year, commencing work in April or May.

The quantity of mud raised prior to the opening of the Junction dock, varied from 12,000 to 29,000 tons, and averaged 19,000 tons per annum; except for a few years before the rebuilding of the Old lock, when, from the bad and leaky state of the gates, a greater supply of water was required for the dock, and the average yearly quantity was about 25,000 tons. As the Junction dock, and in part also the Humber dock, are now supplied from this source, a greater quantity of water flows through the Old dock, and the mud removed has of late been about 23,000 tons a year.

It may be observed, that the greatest quantity of mud is brought into the dock during spring tides, and particularly in dry seasons, when there is not much fresh water in the Hull; in neap tides, and during freshes in the river, very little mud comes in (Timperley 1842).

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter