13 July 1858: A visit to an alum works near Whitby

George Walker’s 1814 portrait of a rather simpler alum works in Yorkshire (Walker 1814).

Walter White. 1861. A Month in Yorkshire, 4th Ed. London: Chapman and Hall. The best of White’s travel writing, in which, as usual, he encounters and investigates the Plain People. This is the golden age of walking, when there were good roads pretty much everywhere, and they hadn’t yet been made inaccessible to pedestrians by cars. His July is told in 31 chapters, which seem to refer to the days of the month. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

It was yet early the next morning when I descended from the high road to the shore at Upgang, about two miles from Whitby. Here we approach a region of manufacturing industry. Wagons pass laden with Mulgrave cement, with big, white lumps of alum, with sulphate of magnesia; the kilns are not far off, and the alum-works at Sandsend are in sight, backed by the wooded heights of Mulgrave Park, the seat of the Marquis of Normanby. Another half-hour, and crossing a beck which descends from those heights, we enter Cleveland, of which the North Riding is made to say,

——If she were not here confined thus in me,

A shire even of herself might well be said to be.

Hereabouts, in the olden time, stood a temple dedicated to Thor, and the place was called Thordisa—a name for which the present East Row is a poor exchange. The alteration, so it is said, was made by the workmen on the commencement of the alum manufacture in 1620. The works, now grimy with smoke, are built between the hill-foot and the sea, a short distance beyond the beck.

The story runs that the manufacture of alum was introduced into Yorkshire early in the seventeenth century by Sir Thomas Chaloner, who had travelled in Italy, and there seen the rock-beds from which the Italians extracted alum. Riding one day in the neighbourhood of Guisborough, he noticed that the foliage of the trees resembled in colour that of the leaves in the alum districts abroad; and afterwards he commenced an alum-work in the hills near that town, sanctioned by a patent from Charles I. One account says that he smuggled over from the Papal States, concealed in casks, workmen who were acquainted with the manufacture, and was excommunicated by the Pope for this daring breach of his own monopoly. The Sandsend works were established a few years later. Subsequently certain courtiers prevailed on the king to break faith with Sir Thomas, and to give one-half of the patent to a rival, which so exasperated the knight that he became a Roundhead, and one of the most relentless foes of the king. A great monopoly of the alum-works was attempted towards the end of the last century by Sir George Colebroke, who, being an East India director, got the name of Shah Allum. His attempt failed.

My request for permission to view the works was freely granted, and I here repeat my acknowledgments for the favour. The foreman, I was told, took but little pains with visitors who came, and said, “Dear me! How very curious!” and yawned, and wanted to go away at the end of ten minutes; but for any one in earnest to see the operations from beginning to end, he would spare no trouble. Just the very man for me I thought; so leaving my knapsack at the office, I followed the boy who was sent to show me the way to the mine. Up the hill, and across fields for about half a mile, brought us to the edge of a huge gap, which at first sight might have been taken for a stone quarry partially changed into the crater of a volcano. At one side clouds of white sulphureous smoke were rising; within lay great heaps resembling brick rubbish; and heaps of shale, and piles of stony balls, and stacks of brushwood; and while one set of men were busily hacking and hewing the great inner walls, others were loading and hauling off the tramway wagons, others pumping, or going to and fro with wheelbarrows.

There was no proper descent from the side to which we came, and to scramble down three or four great steps, each of twenty feet, with perpendicular fronts, was not easy. However, at last I was able to present to the foreman the scrap of paper which I had brought from the office, and to feel sure that such an honest countenance and bright eye as his betokened a willing temper. Nor was I disappointed, for he at once expressed himself ready to show and explain everything that I might wish to see.

“Let us begin at the beginning,” I said; and he led me to the cliff, where the diggers were at work. The formation reminded me of what I had seen in the quarries at Portland: first a layer of earth, then a hard, worthless kind of stone, named the ‘cap’ by the miners; next a deposit of marlstone and ‘doggerhead,’ making altogether a thickness of about fifty feet; and below this comes the great bed of upper lias, one hundred and fifty feet thick; and this lias is the alum shale. Where freshly exposed, its appearance may be likened to slate soaked in grease: it has a greasy or soapy feel between the fingers, but as it oxidises rapidly on exposure to the air, the general colour of the cliff is brown. Here the shale is not worked below seventy-five feet; for every fathom below that becomes more and more bituminous, and more liable to vitrify when burnt, and will not yield alum. At some works, however, the excavation is continued down to ninety feet. Embedded in the shale, most abundant in the upper twenty-five feet, the workmen find nodules of limestone, the piles of balls I had noticed from above, about the size of a cricket-ball; and of these the well-known Mulgrave cement is made. The Marquis, to whom all the land hereabouts belongs, requires that his lessees shall sell to him all the limestone nodules they find. The supply is not small, judging from the great heap which I saw thrown aside in readiness for carting away. Alum shale prevails in the cliffs for twenty-seven miles along the coast of Yorkshire, in which are found one hundred and fifty kinds of ammonites.

Besides balls of limestone, the shale abounds in fossils. It was in this—the lias—that nearly all the specimens, including the gigantic reptiles of the ancient world which we saw in the Museum at Whitby were found. Every stroke of the pick brings them out; and as the shale is soft and easily worked, they are separated without difficulty. You might collect a cartload in half a day. For a few minutes I felt somewhat like a schoolboy in an orchard, and filled my pockets eagerly with the best that came in my way. But ammonites and mussels, when turned to stone, are very heavy, and before the day was over I had to lighten my load: some I placed where passers-by could see them; then I gave some away at houses by the road, till not more than six remained for a corner of my knapsack. And these were quite enough, considering that I had yet to walk nearly three hundred miles.

After the digging comes the burning. A layer of brushwood is made ready on the ground, and upon this the shale is heaped to the height of forty or fifty feet until a respectable little mountain is formed, comprising three thousand tons, or more. The rear of the mass rests against the precipice, and from narrow ledges and projections in this the men tilt their barrow-loads as the elevation increases. The fire, meanwhile, creeps about below, and soon the heap begins to smoke, sending out white sulphureous fumes in clouds that give it the appearance of a volcano.

Such a heap was smouldering and smoking at the mouth of the great excavation, the sulphate of iron, giving off its acid to the clay, converting it thereby into sulphate of alumina. All round the base, and for a few feet upwards, the fire had done its work, and the mass was cooling; but above the creeping glow was still active. The colour is changed by the burning from brown to light reddish yellow, with a streak of darker red running along all the edges of the fragments; and the progress of combustion might be noted by the differences of colour: in some places pale; then a mottled zone, blending upwards with the sweating patches under the smoke. Commonly the heap burns for three months; hence a good manager takes care so to time his fires that a supply of mine—as the calcined shale is technically named—is always in readiness. Fifty tons of this burnt shale are required to make one ton of alum.

We turned to the heap which I have mentioned as resembling a mound of brick rubbish at a distance. One-third of it had been wheeled away to the cisterns, exposing the interior, and I could see how the fire had touched every part, and left its traces in the change of colour and the narrow red border round each calcined chip. The pieces lie loosely together, so that on digging away below, the upper part falls of itself. The man who was filling the barrows had hacked out a cavernous hollow; it seemed that a slip might be momentarily expected, for the top overhung threateningly, and yet he continued to hack and dig with apparent unconcern, and replied to the foreman’s caution, “Oh! it won’t come down afore to-morrow. It’ll give warning.”

Now for the watery ordeal. On the sloping ground between the cliffs and the sea, shallow pits or cisterns are sunk, nearly fifty feet long and twenty wide, and so placed, with a bottom sloping from a depth of one foot at one end to two feet at the other, as to communicate easily with one another by pipes and gutters. Whether alum-works shall pay or not, is said to depend in no small degree on the proper arrangement of the pits. Each pit will contain forty wagon-loads of the mine. As soon as it is full, liquor is pumped into it from a deep cistern covered by a shed, and this at the end of three days is drawn off by the tap at the lower end, and when drained the pit is again pumped full and soaked for two days. Yet once more is it pumped full, but with water—producing first, second, and third run, and sometimes a fourth—but the last is the weakest, and is kept to be pumped up as liquor on a fresh pit for first run. It would be poor economy to evaporate so weak a solution. Each pit employs five men.

All this is carried on in the open air, with the sea lashing the shore but a few yards off, and all around the signs of what to a stranger appears but a rough and ready system. And in truth there must be something wasteful in it, for all the alum is never abstracted. After the third or fourth washing, the mine is shovelled from the pits and flung away on the beach, where the sea soon levels it to a uniform slope. In one of the so-called exhausted pits I saw many pieces touched, as it were, by hoar frost, which was nothing but minute crystals of alum formed on the surface, strongly acid to the taste.

The rest of the process was to be seen down at the works, so thither we went; not by the way I came, for the foreman, scrambling up the side of the gap, conducted me along the ledge at the top of the burning heap. He walked through the stifling fumes without annoyance, while on me they produced a painful sense of choking, with an impulse to run. Before we had passed, however, he pushed aside a few of the upper pieces, and showed me the dull glow of the fire beneath. Then we had more ledges along the face of the cliff, and now and then to creep and jump; and we crossed an old digging, which looked ugly with its heaps of waste and half-starved patches of grass. All the way extends a course of long wooden gutters, in which the first-run liquor was flowing in a continuous stream to undergo its final treatment—another trial by fire.

Then into a low, darksome shed, where from one end to the other you see nothing but leaden evaporating pans and cisterns, some steaming, and all containing liquor in different states of preparation. That from which the most water has been evaporated—the concentrated solution—has a large cistern to itself, where its tendency to crystallize is assisted by an admixture of liquor containing ammonia in solution, and immediately the alum falls to the bottom in countless crystals. The liquor above them, now become ‘mother liquor,’ or more familiarly ‘mothers,’ is drawn off, the crystals are washed clean in water, are again dissolved, and once more boiled, mixed with gallons of mothers remaining from former boilings. When of the required density, the liquor is run off from the pan to the ‘roching casks’—great butts rather, big as a sugar hogshead, and taller; and in these is left to cool and crystallize after its manner, from eight to ten days, according to the season. The butts are constructed so as to take to pieces easily, and at the right time the hoops are knocked off, the staves removed, and there on the floor stands a great white cask of alum, solid all over, top, bottom, and sides, except in its centre a quantity of liquor which has not crystallized. This having been drawn off by a hole driven through, the mass is then broken to pieces, and is fit for the market; and for the use of dyers, leather-dressers, druggists, tallow-chandlers; for bakers even, and other crafty traders.

Looked at from the outside, there is no beauty in the cask of alum; but as soon as the interior is exposed, then the numberless crystals shooting from every part, glisten again as the light streams in upon them; and you acknowledge that the cunning by which they have been produced from the dull slaty shale is a happy triumph of chemical art—one that will stand a comparison with a recent triumph, the extraction of brilliantly white candles from the great brown peat-bogs of Ireland, or from Rangoon tar. Perhaps some readers will remember the beautiful specimen of alum crystals—an entire half-tun that stood in the nave of the Great Exhibition.

Alum is made near Glasgow from the shale of abandoned coal mines, soaked in water without burning. After the works had been carried on for some years, and the heap of refuse had spread over the neighbourhood to an inconvenient extent, it was found that on burning this waste shale, it would yield a second profitable supply of alum. Moreover, artificial alum is manufactured in considerable quantities from a mixture of clay and sulphuric acid.

In going about the works it was impossible not to be struck by the contrast between the sooty aspect of the roofs, beams, and gangways, and the whiteness of the crystal fringes in the pans, and the snowy patches here and there where the vapour had condensed. And in an outhouse wagon-loads of ‘rough Epsoms’ lay in a great white heap on the black floor. This rough Epsoms, or sulphate of magnesia, is the crystals thrown down by the mother-liquor after a second boiling.

In our goings to and fro, we talked of other things as well as alum; of that other mineral wealth, the ironstone, to which Cleveland owes so important a development of industry within the past fifteen years. The existence of ironstone in the district had long been known; but not till the foreman—jointly with his father—discovered a deposit near Skinningrave, and drew attention to it, was any attempt made to work it. Geologically the deposit is known as clayband ironstone; hence clay will still make known the fame of this corner of Yorkshire, as when the old couplet was current—

Cleveland in the clay,

Carry in two shoon, bring one away.

If I liked the foreman at first sight, much more did I like him upon acquaintance. He won my esteem as much by his frank and manly bearing, as by his patient attentions and intelligent explanations; and I shook his hand at parting with a sincere hope of having another talk with him some day.

Comment

Comment

No 13 of the 31 chapters constituting White’s month of July, so I’m guessing the 13th.

Are there remains of this works? The Peak Alum Works near Ravenscar sounds worth a visit.

Mulgrave cement is more commonly known as Atkinson’s cement, after William Atkinson, architect of Georgian Gothic country houses but also an industrial entrepreneur:

Besides architecture, Atkinson’s great interests were chemistry, geology, and particularly botany. He combined the first two when, about 1810, he successfully introduced to the London market a Roman cement, known as Atkinson’s cement, which could be used either externally or internally as stucco or rendering. Its significant ingredient, calcareous clay, he extracted from land in north Yorkshire belonging to the 1st Earl of Mulgrave, for whom he had recently remodelled Mulgrave Castle, near Whitby; he then shipped the clay to Westminster, where he owned a wharf (Wikipedia contributors 2021).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

23 April 1642: Having promised parliament to safeguard for it Hull’s crucial arsenal, John Hotham tells it how today he shut the gates of Hull to Charles I

23 April 1642: Having promised parliament to safeguard for it Hull’s crucial arsenal, John Hotham tells it how today he shut the gates of Hull to Charles I

Comment

Comment

Rimbault quotes one John Gregory, who in the Sarum Processionale found the following:

The Episcopus Choristarum was a chorister-bishop chosen by his fellow children upon St. Nicholas’ day… From this day till Innocents’ day at night (it lasted longer at the first), the Episcopus Puerorum [Boy-Bishop] was to bear the name and hold up the state of a bishop, answerably habited, with a crosier or pastoral staff in his hand, and a miter upon his head; and such an one too som had, as was multis episcoporum mitris sumtuosior, saith one – very much richer than those of bishops indeed. The rest of his fellows from the same time being were to take upon them the style and counterfeit of prebends, yielding to their bishops (or else as if it were) no less then canonical obedience. And look what service the very bishop himself with his dean and prebends (had they been to officiate) was to have performed, the mass excepted, the verie same was done by the chorister-bishop and his canons upon this Eve and the Holy Day.

This may be the origin of the York ritual, which nevertheless, and for reasons unknown to me, starts and ends later. The “account of Nicholas of Newark, guardian of the property of John de Cave, boy bishop in the year of our Lord 96” accounts for receipts (offerings in the cathedral, from canons, and from the nobility and monasteries visited) and expenditure (clothing, beer, food, music, etc.). The world-turned-upside-down visitations of the episcopus puerorum/Innocencium and his band remind me somewhat like those practised by the Raad van Elf of carnival associations in the Catholic Netherlands. Was there a similar serious business + drunken fun combination? For example, “the medieval breviary in the Sarum (but not in the Roman) use prescribed ‘O Virgo Virginum’ as antiphon upon the Magnificat for December 23, but was it sung for the boy-bishop on 23 December in humorous reference to his postulated sexual inexperience?

O Virgin of Virgins, how shall this be? For neither before thee was any like thee, nor shall there be after. Daughters of Jerusalem, why marvel ye at me? That which ye behold is a divine mystery (Bls 2007/12/23).

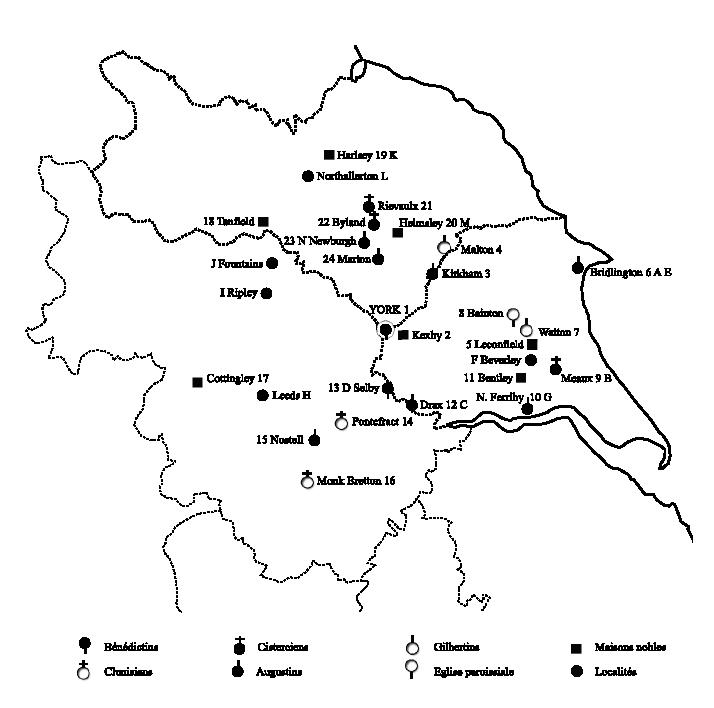

Yann Dahhaoui has compiled a map showing the locations visited by John de Cave numbered in chronological order:

There is a 13th century sculpture of what some say is a boy bishop at the marvellous St Oswald’s Church, Filey – the church guide suggests that it might instead by

one of the canons regular of St Augustine, a member of Bridlington Priory who served the church at Filey. It was not uncommon in the 13th and 14th centuries for such a person to keep up his connection with the church by having his heart buried there with an appropriate miniature representation of himself in stone.

The account documents 42 days starting on 23 December, but I don’t know how long John de Cave’s rule actually lasted. Liz Truss managed 49 days.

Irrelevant, but St. William is presumably William of Donjeon/Bourges, whose feast day is 10 January, to which 7 January was the closest Sunday.

https://archive.org/details/stationsofsunhis0000hutt/page/100/mode/1up

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter