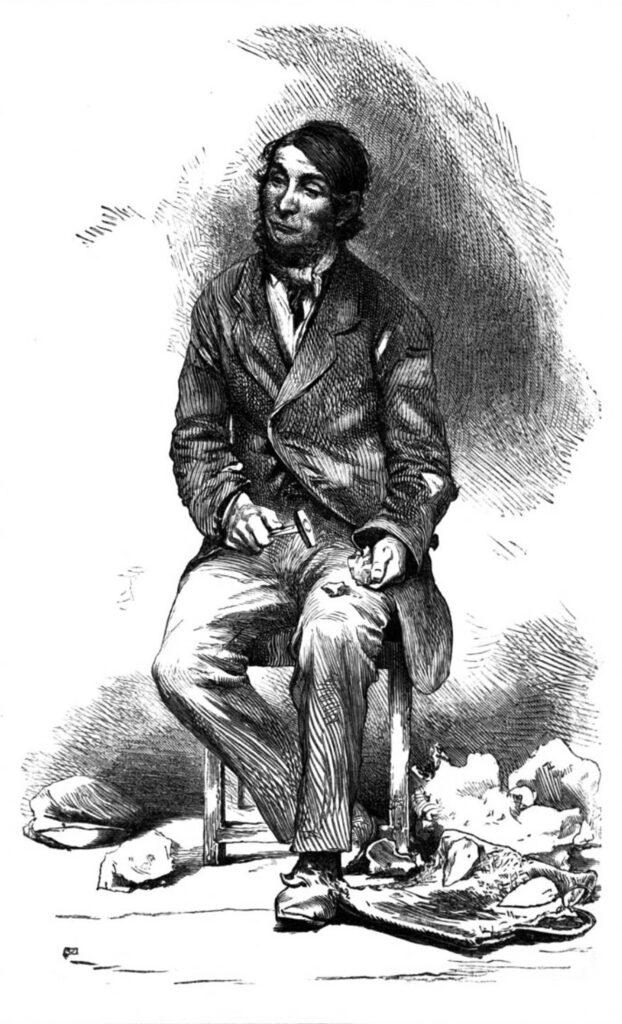

6 January 1862: “Flint Jack” of Whitby, an antiquarian forger, demonstrates knapping at a London lecture on the ancient flint implements of Yorkshire

Flint Jack knapping imitation prehistoric handaxes, here using an iron, which is to say post-Stone-Age, hammer (Jewitt 1867/10).

People’s Magazine. 1867/07/06. Flint Jack. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

FLINT JACK.

I.

On the 6th of January, 1862, a considerable gathering of geologists and their friends took place at the rooms in Cavendish Square, in which, at that time, the meetings of the Geologists Association were held, under the presidency of Professor Tennant. Two popular subjects were announced for the evening’s consideration; the one being “On Lime and Lime-stones,” by the President; the other, “On the ancient Flint Implements of Yorkshire, and the Modern Fabrication of similar specimens,” by the Rev. Thomas Wiltshire, the Vice-president.

These announcements attracted a full attendance of members, and of their wives and daughters. The ladies rapidly filled the upper portion of the lecture-room nearest the platform; but courteously left the foremost row of seats to be occupied by the friends of the President and the Committee. It soon became evident that it was to be a crowded meeting, and as the back seats gradually filled, many a wistful glance was cast at these reserved seats; yet, by common consent, they were left vacant. Presently, however, an individual made his way through the crowd whose strange appearance drew all eyes towards him, and whose effrontery in advancing to the foremost seats, and coolly sitting down in one of them, was greeted by a suppressed titter on the part of the ladies. He was a weather-beaten man of about forty-five years of age, and he came in dirty tattered clothes, and heavy navvy’s boots, to take precedence of the whole assemblage: it was natural, therefore, that the time spent in waiting for the President’s appearance should be occupied in taking an inventory of his curious costume and effects.

He wore a dark cloth coat, hanging in not unpicturesque rags about the elbows; it was buttoned over a cotton shirt which might once have been white, but which had degenerated to a yellow brown. About his neck was a fragment of a blue cotton handkerchief; his skin was of a gipsy brown, his hair hung in lank black locks about a forehead and face that were not altogether unprepossessing, except for the furtive and cunning glances which he occasionally cast around him from eyes that did not correspond with each other in size and expression. His corduroys, which were in a sorry condition, had been turned up; and their owner had evidently travelled through heavy clay, the dried remains of which bedaubed his boots. Altogether he was a puzzling object to the ladies; he had not the robust health or the cleanliness of a railway navvy; he differed from all known species of the London working man; he could scarcely be an ordinary beggar “on the tramp,” for by what means could such an individual have gained admittance to a lecture-room in Cavendish Square? Yet this last character was the one best represented by the general appearance of the man, who carried an old greasy hat in one hand, and in the other a small bundle tied up in a dingy red cotton handkerchief. The most amusing part was the comfortable assurance with which he took his seat, unchallenged by any of the officials, and the way in which he made himself at home by depositing on the floor, on one side his hat, on the other side his little red bundle, and then set to work to study the diagrams and specimens which were displayed on the platform.

At length the President, Vice-president, and Committee entered the room, and the business of the evening commenced. Many glances were cast at the stranger by the members of the Committee, but no one seemed astonished or annoyed at his presence; and, in fact, he was allowed to retain the prominent position which he had chosen for himself. He listened attentively to the President’s lecture, and to the discussion which followed; but his countenance betrayed a keener interest when the second paper of the evening, that on Yorkshire Flint Implements, was read. And here the mystery of the stranger was suddenly revealed, for in the course of his remarks on the clever fabrications of modern times, by which these ancient flint instruments were successfully copied, the Vice-president stated, that, through the efforts of Professor Tennant, a person was in attendance who, with the aid of only a small piece of iron rod, bent at the end, would, with remarkable dexterity, produce almost any form of flint weapon desired. He then desired the stranger to mount the platform, and the man, taking up his hat and bundle, seated himself in a conspicuous position, and prepared to exhibit his skill. He undid the knots of his red handkerchief, which proved to be full of fragments of flint. He turned them over, and selected a small piece, which he held sometimes on his knee, sometimes in the palm of his hand, and gave it a few careless blows with what looked like a crooked nail. In a few minutes he had produced a small arrow-head, which he handed to a gentleman near, and went on fabricating another with a facility and rapidity which proved long practice. Soon a crowd had collected round the forger, while his fragments of flint were fast converted into different varieties of arrow-heads, and exchanged for sixpences among the audience.

This was the first appearance before the public, in London, of the celebrated “Flint Jack,” whose life and adventures have since been traced with some minuteness, and have recently received their finishing touches from his own confessions and from his committal to Bedford Jail.

According to his own account, the individual known, among other names, as Flint Jack, was born in the year 1815, at Sleights, near Whitby, in Yorkshire. His real name is Edward Simpson; his father was a sailor; and the boy appears to have led a respectable life, earning his living, from the age of fourteen, as servant or assistant to gentlemen engaged in geo- logical pursuits. Against this, we must mention that some of those who know him best deny that his dialect is that of a Yorkshireman, and point to one of the names by which he was known twenty years ago (“Cockney Bill,”) as suggesting a more likely origin. However this may be, Simpson has gained credit, and has satisfactorily accounted for his own knowledge of geology, by stating that for five years he was in the service of Dr. Young, the historian of Whitby. and was a constant attendant on all his fossil-hunting expeditions. Subsequently (as he affirms) he entered on a similar engagement with Dr. Ripley, also of Whitby, with whom he remained six years. On the death of his master, in 1840, he seems to have commenced business on his own account, wandering about the neighbourhood of Whitby, gathering and selling fossils. At any rate, it was at this time that he became well known on the Yorkshire coast, and acquired the name of Fossil Willy. He was then engaged in honest traffic. The young man is described as more than ordinarily intelligent; and he appears both then and afterwards to have had a great delight in beautiful scenery, and in the rambling life which continually brought him into fresh localities.

In 1841 Fossil Willy was carrying on a successful trade with two gentlemen in Scarborough, who were collectors of fossils. He included Filey and Bridlington in his walks, and became “very handy” in cleaning fossils. All his rambles were performed on foot; and he seems at this period to have led a pleasant life, and to have been tolerably well off. We have no clear account of the circumstances under which he began to net dishonestly. It was at Whitby, in 1843, according to his own account, that he saw a British barbed arrow-head for the first time, and was asked if he could imitate it. If this really was the suggestion of some other mind than his own, the tempter has much to answer for. The flint arrow-head which he copied led to his downfall; it was the commencement of a long series of forgeries, and the extinction of Jack’s honest trade. To search for the real objects was a work of time and labour; to manufacture spurious ones became so easy and so profitable that the temptation was too great for the individual henceforth appropriately named Flint Jack. His earlier efforts, how ever, in this new traffic, were comparatively clumsy. He could not settle on the best form of tool, and at last he discovered it by mere accident. Taking up, one day, the hasp of a gate which was loose, he struck a blow with it on a flint, and a fine flake fell off, of a size and form which, by a little chipping of the edges, could easily be converted into an arrow-head. This it became evident that a curved piece of iron was the tool required, and Jack was no longer at a loss. A bit of iron rod six or eight inches long, and curved at the ends, is still his chief tool, to which he sometimes adds a small round-faced hammer of soft iron, and a common bradawl. But Jack can make a water-worn pebble from the sea-beach to answer his purpose, on an emergency, as well as the hammer.

The trade on which Jack had now entered required a considerable knowledge of antiquities, and he took care to avail himself of any opportunities which came in his way of visiting museums and private collections. In this manner he became acquainted with the forms and materials of urns, beads, seals, &c., with a view to their imitation. In the beginning of 1844 he was assisting an antiquarian at Bridlington to form a collection of British flints. The genuine ones are abundant in that neighbourhood; but Jack was able to supplement his gatherings to any extent by his own fabrications. In the sale of these, and in the collection of materials for his manufacture, he is said to have walked, ordinarily, thirty or forty miles a day, distributing among purchasers his ancient stone and flint implements with a lavish hand, of which the neighbourhood still bears traces. One of his Bridlington customers (Mr. Tindall), speaking of a purchase made by him of thirty-five flint implements, says, “I bought them because they differed much in their make and shape from any that I had found myself. They were very dirty, and I could not get them clean with cold water, so I put eight or nine of the dirtiest into a saucepan, and boiled them. When I drained off the water I found that several of them were made up of splinters struck from the flint when in course of being made, and which Cockney Bill had joined together with boiled alum to make them perfect.”

Jack was always careful to give the history of his specimens, and to describe the localities and the tumuli whence they were obtained. He sold to the gentleman just named an apparently ancient urn, which he said he had extracted from a tumulus on a certain farm called East Hunton. Immediately afterwards, Mr. Tindall took three men with him to the locality, and having discovered and opened the tumulus, he actually found two urns, several flint implements, and an axe-head of stone; but he is quite certain that this tumulus had never been opened previously. What, then, was the history of Jack’s ancient urn? It was simply this. The cunning fellow knew that the neighbourhood was pretty well stocked with arrow-heads; he was also aware that these implements are often found accompanied by urns, and that it might reasonably be expected by his patrons that in finding the one he would sometimes light upon the other. He had therefore established, in a secret place among the cliffs of Bridlington Bay, a manufacture of “ancient pottery,” and this urn was probably the fruit of his own industry. A wild and solitary life must have been that of this ancient potter, as he moulded his clay into the rude shapes of which he had seen specimens in museums, and then set them out to dry in sheltered places among the rocks, finishing by a slight firing of the articles by means of dried grass, and brambles. Jack’s early productions in this way appear to have gulled the public; but they did not satisfy his own correct taste. Later in his career he spoke with great contempt of his early manufacture of urns. The windy cliffs among which he worked were found unfavourable, and he removed to a more sheltered and wooded region about Stainton Dale, between Whitby and Scarborough, where he was equally screened from observation, and where he built himself a hut, and carried on his pottery works. After a large baking of urns he would set off to some favourable mart for their sale. On one occasion he sold an ancient urn to a gentleman in Bridlington, which was so much valued by the owner, that on accidentally letting it fall, and breaking it to pieces, he gave it back to Jack for repair, and paid him handsomely for joining the fragments together in a clever way. A few days afterwards, however, there was discovered, in a corner of the room where the accident had happened to the urn, a large portion of the bottom and side of the same, which had been overlooked when the fragments were given to Jack. This untoward discovery shook Jack’s credit in Bridlington, and doubtless caused him to turn his steps in another direction.

In a future notice we shall trace his further wanderings, and the audacious counterfeits on which he subsequently ventured.

Comment

Comment

Several other sources I enjoyed: Parry Thornton tries to establish “his antecedents and birth; his early life and associations; and his introduction or inducement to forgery” (Thornton 2002); Llewellynn Jewitt’s memoir (Jewitt 1867/10); William Henry Goss’s tribute to Llewellynn Jewitt (Goss 1889); Dickens casts more light on Flint Jack’s knapping technique (Dickens 1867/03/09); an approximation to Thomas Wiltshire’s talk that evening (Wiltshire 1861).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

Comment

Comment

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter