11 March 1864: An inhabitant of Bacon Island survives the Great Sheffield Flood

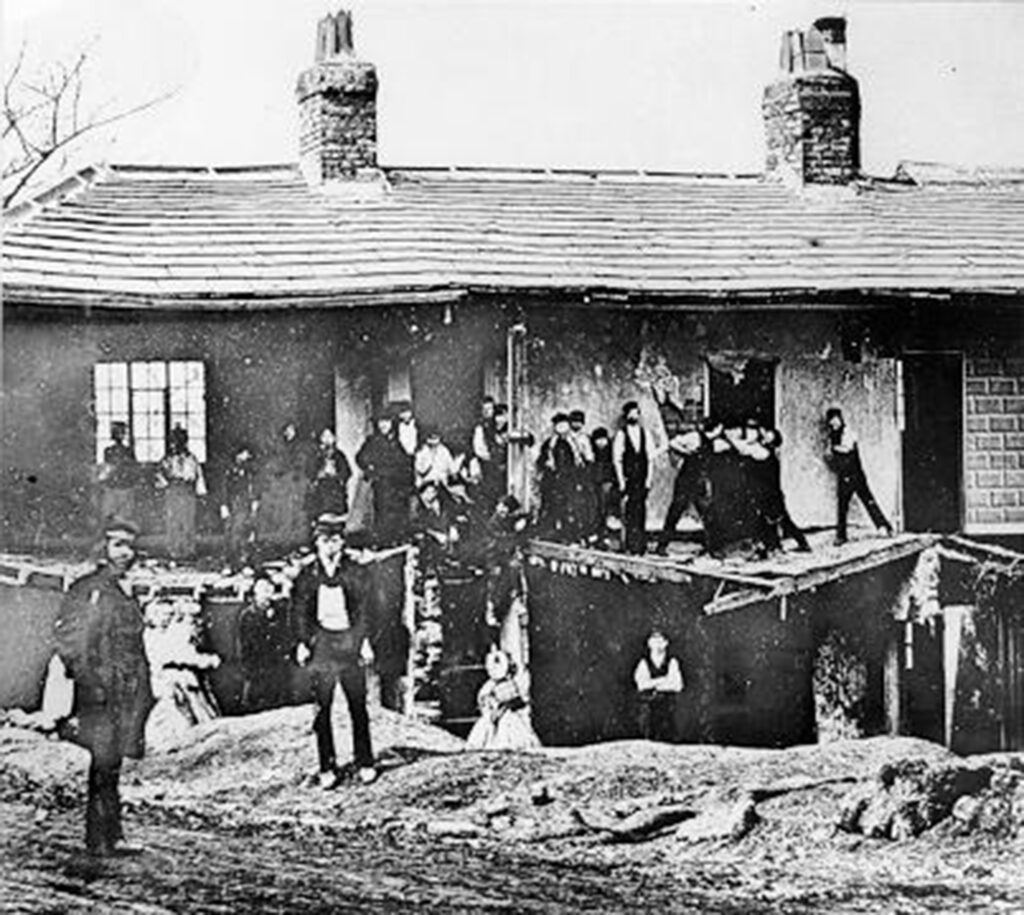

Houses, possibly at Philadelphia at the southern end of Bacon Island, during the Great Cleanup (Anon 1864).

Times. 1864/03/16. The Calamity at Sheffield. London. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

Writing to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, a correspondent who resided on Bacon-island, thus describes what he saw in a glimpse of the flood:

I was seated at my fireside a little after 12 o’clock on Saturday morning when my attention was arrested by a strange noise, together with a shouting of many people. Alarmed, I hastened to my front door; upon opening it I was completely bewildered by the frightful sound that fell upon my ears. It has never yet been truly described, nor can it ever be; the nearest approach to a correct definition of it that I have heard was that of a poor man whose house withstood the storm that swept away his furniture, &c. ‘Sir,’ said he to me, ‘I heard it coming just like hissing thunder.’ I was so stupefied by this horrid sound that I did not see the wild waters immediately before me, nor did I dream of the nature of the calamity by which I was threatened, until I actually stepped into the water at my garden gate. I at once mounted the railings, and was terrified by the sight of the rushing flood. Sharman’s house was immediately opposite, only across the road. My eye had but just caught the waters foaming at its base, when the end fell into the flood, affording a glimpse of the rooms, furniture, &c. It was but a glimpse, for in a moment the remainder of the house fell towards the road, and sank like lead in the waters, not leaving the slightest vestige visible. As I was not aware that Sharman and his family had escaped a few minutes before, I supposed they were all lost, and a thrill of horror came over me that caused me to turn my head from the deep that had, as I supposed, swallowed them up. I then perceived that the waters had risen, and surrounded me in my garden. I at once leapt back and retreated into my house, which is considerably elevated above the road. The stream rose rapidly, until it reached 4ft. above the level which it had attained when it swept away Sharman’s house. As it had now reached my doorstep, I requested that my children should be taken out of their beds and carried to a neighbouring house on higher ground. Before this could be done I fancied the waters ceased to rise; presently I had the happiness to see that they were subsiding, so that anxiety for my family and myself was at an end. When the flood invaded it rose rapidly, but when it retired it seemed to sink slowly, very slowly. At length the road was clear of water (not of mud); we then perceived that the bridge leading to the island was swept away. Anxiety to know the fate of the cottagers on the island constrained some to creep over the top of the shuttle. I essayed to follow, and succeeded. Up on reaching the other side we found we were landed in chaos, and had to grope our way (the darkness was terrible) through thick mud, under and over trees, timber, stones, and wrecks of every kind. Upon reaching the cottages we were rejoiced to find all their inhabitants safe, excepting poor Wright, his wife, and the little girl who was visiting with them. The end of Wright’s house jutted out into the stream which brought down a beam that broke a large hole through it; into this the stream poured until it threw down the front of the house, carrying away the door, the stairs, all the furniture, and we think Wright, his wife, and the child too; but, as the flood never reached the chamber in this house, we are driven to the conclusion that the three persons who perished must have been down stairs.

Comment

Comment

The rest of the article:

THE CALAMITY AT SHEFFIELD

The great mass of the flood waters seems now to have passed off from the Don, and the streets in its neighbourhood at Sheffield begin to wear somewhat of their old appearance. Not so, however, with the district over which the deluge poured. Many months must elapse before the buildings are restored, and years must go by before the face of the country can wear the aspect of verdure and careful cultivation which it bore on Friday night. The river, though fallen, is far from being as low as it generally is at this time of the year, and every furlong of the stream’s banks exhibits almost innumerable traces of the inundation – such as trees, balks, and beams of timber firmly embedded in its bed. The open land in this neighbourhood is still for the greater portion under water, and, as that drains off, a number of bodies will, it is feared, be exposed to view. The large hollows which abound are being filled up by the hundreds of cartloads of mud which are being deposited in them. The great manufacturers are busily engaged cleaning out their warehouses, and polishing their machinery, which had become rusty by the water. Harvest-lane presents the same picture of mud, cinders, dead horses, cows, and pigs that it did on Sunday. Bridgehouses was as busy as ever. The Whiterails has been cleared. A great portion of the thick deposit of mud has been carted away, giving the street somewhat of its usual appearance. In Nursery-street, with its now silent manufactories, is the Lady’s-bridge. A great portion of the rubbish has been removed from beneath the arches, and the water now flows freely on as far as the Blonk-bridge, where the stream is still impeded by a mass of rubbish. Blonk-street yet remains in the same state as on Sunday. The works in this vicinity are also stopped for repairs. As a rule, however, the damage done to the great manufacturers in the town has been slight. Mr. John Brown’s works and those of Mr. Bessemer escaped without any injury, and were at work as usual on the Monday following the calamity. Messrs. Cammals’ works were only deranged, so to speak; but the new works building for Messrs. Naylor Vickers were rather seriously damaged. Round Neepsend and by Hillsborough and Owlerton-road, where the great mischief fell, the inhabitants of the houses are busily engaged pumping the water out of their cellars. “Wallers” and masons are engaged in rebuilding, wherever practicable, the walls that have been washed down. Further down in the gardens opposite, at the other side of the river, a very painful incident occurred. Two or three men were engaged in removing the rubbish of one of the small, inhabited garden-houses. Near them stood a young woman, with two children clinging to her dress, the only ones saved from the wreck of their cottage. The rubbish had almost been cleared away when the leg of a human being was exposed to view. Brick after brick was removed, until the poor woman recognized the remains of her husband. A little above where this incident occurred the corpse of a child was brought out of the mud in an open space near the Old Brewery. About 20 yards from this the body of a man was also found. As these bodies were carried on stretchers to the workhouse a large crowd followed, but the greatest order and decorum were observed by every one.

[Excerpt above]

In the Kelham rolling mills the escape of the workmen was very narrow indeed. The first alarm was given by a man who had been asleep at the bottom end of the mill, and who was awoke by the rushing in of the waters. He hastened to where his fellow-workmen were getting dinner – these men being what are called the “night shift” – and gave them warning. Fortunately, the gates of the yard were closed, and the men had no means of getting out by these means. Had they done so they would inevitably have been swept away by the tide which passed in front of the buildings. They climbed on the roof, and, as has already been told, contrived, in their extreme eagerness to escape, to set it on fire in doing so. But the more remarkable circumstance remains to be told. The man who gave the alarm, and who was the means of saving the lives of so many of his fellow-workmen, lost his father, mother, wife, and two children, who lived at Malin-bridge; and his own bedstead, with other of his furniture, floated into the mills where he, with others, was a prisoner – a distance of not less than 2½ miles. In another part of Kelham island a man and his wife, who occupied a small cottage, on hearing the noise of the waters, went out to save their pig. Both were swept away by the torrent, and the pig as well.

Michael Armitage’s flood site – whence the photo – is brilliant. I must also introduce this excavation of the Kelham Rolling Mills site, with its Charles Peace connection.

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

4 July 1838: 26 girls and boys drown trying to escape via a tunnel from flash flooding in Huskar Colliery, Silkstone, Barnsley, after the steam lifts fail during a rainstorm

4 July 1838: 26 girls and boys drown trying to escape via a tunnel from flash flooding in Huskar Colliery, Silkstone, Barnsley, after the steam lifts fail during a rainstorm

Comment

Comment

The scan is from Chris Hobbs, who has a great collection of information on Horatio Bright. The mausoleum is at 53.389403,-1.645310, and was robbed in the 1980s, after which the bodies were reinterred at Crookes Cemetery, not at Ecclesfield Jewish Cemetery as Judy Simons claims (Simons 2021). Mary Alice and Samuel Bright had died in 1891. Hobbs says that Mary Alice “was embalmed and placed in a glass sided coffin. The mausoleum was decorated with pictures, statutes and ornaments and fitted with mahogany panelling. He even installed a small hand operated organ so that he could play funeral music to his departed love ones on his frequent visits.” The organ story may or may not be true, but our reporter specifically rebuts the first two claims. Given Bright’s atheism, or agnosticism, or personal faith, I’m curious who paid for the Methodist chapel adjoining the plantation in which he was laid to rest:

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter