14 December 1866: At quarter to five in the morning, the signal bell rings and a voice calls out from the depths of Oaks Colliery (Barnsley), tomb to 361 men and boys in the last day and a half

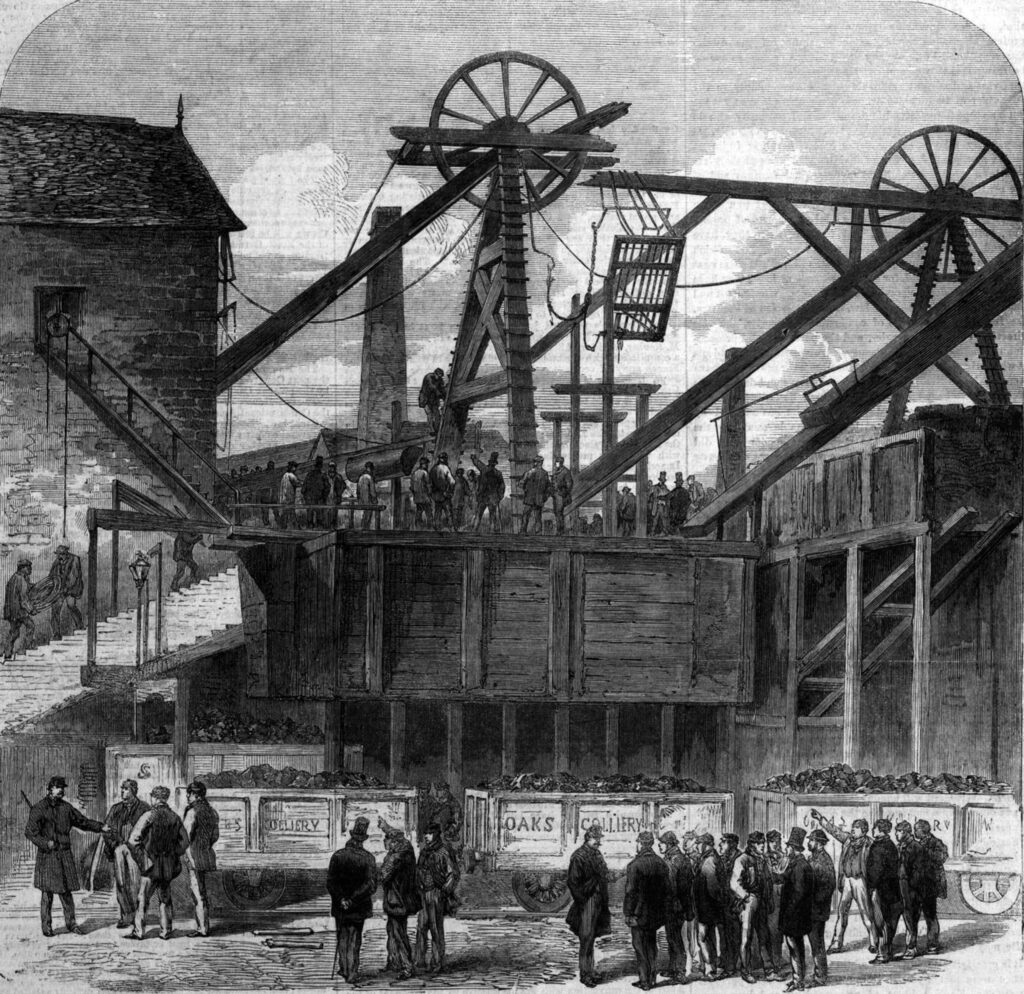

Cage thrown up into the headgear at the pit mouth by the second explosion at the Oaks Colliery, Barnsley (Illustrated London News 1866/12/29).

John Thomas Jeffcock. 1867. Parkin Jeffcock, Civil and Mining Engineer. London: Bemrose and Lothian. The Google Books scan lacks page 122. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

At about a quarter to five that morning, Mr. Mammatt and several others who were at the pit mouth, were astonished at hearing some one at the bottom of the shaft ringing the signal-bell; they listened and heard a voice; and then let down to him by a spare signal wire, a bottle of brandy and water, which he took off. But how was he to be reached, for the last explosion had broken the head-gear of the pits, and shattered the cage? A man was sent to get up the steam at the little saw-mill engine, to which was attached a small drum. A staff of men were sent to the furnace pit to remove the gin rope, and bring it to No. I pit, where it was fixed to the drum, and passed over a pulley; and to the end of it was attached a trunk or iron bucket, not much bigger than a fish-kettle, with a strong hoop of iron bent over it for a handle. In this bucket the explorers were to swing down the 280 yards into this grave of death, to rescue the imprisoned man. Mr. Mammatt, the engineer in immediate charge, at once volunteered to descend; and on Mr. Woodhouse, the engineer-in-chief’s asking if any one of light weight would go with him, Mr. Embleton Junior immediately volunteered. But the chief would not allow him to do so, unless his father’s consent, who was within call, were first obtained to his leading the forlorn hope. The father at once said ‘Yes, he must go;’ and when the engine-man faltered and declared he could not let them down through want of nerve, the brave father stood by him at his engine the whole time, and gave him confidence. Some of the engineers on the top lay on the ground with their ears over the shaft, to hear the words they might shout as they went down; and a string of men was formed to pass the orders on to the engine-man.

In about two hours from the signal-bell’s first sounding, the two brave young men began their perilous descent. Each placed one foot in the ‘trunk,’ the other hanging over the side; and securing four lighted safety lamps from the wet under the shelter of their clothes, clutched the rope with one hand, while the other was free to steady themselves. The rope had been hurriedly put on the drum, and, not being wound evenly, jerked the trunk about as they descended, while at times it spun round so that only with the greatest difficulty could they keep themselves with their spare arm free from the side, or avoid losing their heads through dizziness. To keep their presence of mind, and steady their heads in the darkness, according to their chief’s advice, they kept talking to each other, as they slowly, at times almost imperceptibly, went down the shaft. They did not think they should both return alive. But the apprehension of being caught by another explosion was over-matched by the anticipation of the ghastly sight which they might encounter among the dead below. When they had been lowered about one hundred and fifty yards, they found the ‘cribs’ on the side of the shaft were burst, and the water, instead of passing along the ‘drift’ to the pumping engine pit, showered down upon them in a stream almost as thick as a man’s body, soaking them through and through, and with its deafening roar making it well-nigh impossible to give or receive orders, or communicate at all with those on the surface. As they passed the ‘drift’ and other way-marks, they shouted to those above to inform them of their where-abouts.

At last, after quarter of an hour’s slow and cautious descent, they reached the bottom, and got out safely in spite of a broad ‘sump’ or well, below them at the pit bottom, nine yards deep – the ordinary scaffold floor above which, had been broken away by the explosions. They advanced into the pit a little way, shouting to the man, but got no answer. At last they heard a faint reply, and found the poor fellow, Samuel Brown, one of the volunteers of the preceding day, sitting on a heap of rubbish a few feet from the pit bottom. He said he alone was living in the pit, but could not give any very coherent answer to Mr. Mammatt’s questions; he only feebly said “Take me out, take me out.” They took him to the bucket, and tied him in securely with some thongs three yards long, which they had brought. Forty or fifty yards down the engine plane they saw a mass of wagons of coal, the last gettings of Wednesday, all on fire, raging like a furnace, and pouring out heat and smoke up No. 2 shaft, nearest which they lay, which served to light up most terribly the passages and corridors of the mine, and at the same time to freshen the air between the two shafts; but it would have been wanton risk of death to have gone further in. They shouted ‘Jeffcock,’ ‘David,’ ‘Barker,’ but no voice answered. They now began to make ready for the re-ascent. As Mr. Mammatt placed his foot into the bucket, it tilted over, and threw him into the deep ‘sump’ filled with nine feet of water. He flung out his arms, however, and catching hold of an iron bar which was lying over it, saved himself with some difficulty from being drowned. They now shouted to those above to ‘bend up;’ but amidst the roar and din of the fire and of the water, it was impossible for those on the pit-bank to make out the meaning of their shout. One man, however, who was more accustomed than the rest to Mr. Mammatt’s voice, at last distinguished his words. They were then drawn up more rapidly than they descended; and at length, with the rescued man, they safely reached the pit-bank, to the heartfelt delight of the engineers above, and to the admiration of all who love a gallant deed.

Comment

Comment

Influenced passage of the 1872 Coal Mines Act.

This blog post from the Notts Mining Museum is good.

From the report by Dickinson, Inspector of Mines:

The jury, after, as it appeared, a good deal of discussion, agreed to the following verdict: “That Richard Hunt and others were killed by an explosion of gas or fire-damp at the Oaks Colliery on the 12th of December 1866, but there is no evidence to prove where or how it ignited. The jury think it unnecessary to make any special recommendations as to the working of mines, seeing that the Government are collecting information no doubt with a view of the better protection of life, but they think a more strict inspection desirable” (House of Commons 1867)

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

4 July 1838: 26 girls and boys drown trying to escape via a tunnel from flash flooding in Huskar Colliery, Silkstone, Barnsley, after the steam lifts fail during a rainstorm

4 July 1838: 26 girls and boys drown trying to escape via a tunnel from flash flooding in Huskar Colliery, Silkstone, Barnsley, after the steam lifts fail during a rainstorm 17 November 1812: A doggerel inscription at St. George’s, Doncaster, commemorates two sons of ringing master Robert Smith, one of whom died by his father’s bells

17 November 1812: A doggerel inscription at St. George’s, Doncaster, commemorates two sons of ringing master Robert Smith, one of whom died by his father’s bells

Comment

Comment

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter