12 April 1875: The Times says that the ventilation tubes patented by Martin Tobin, a retired Leeds merchant, have ended air pollution in the borough’s police court

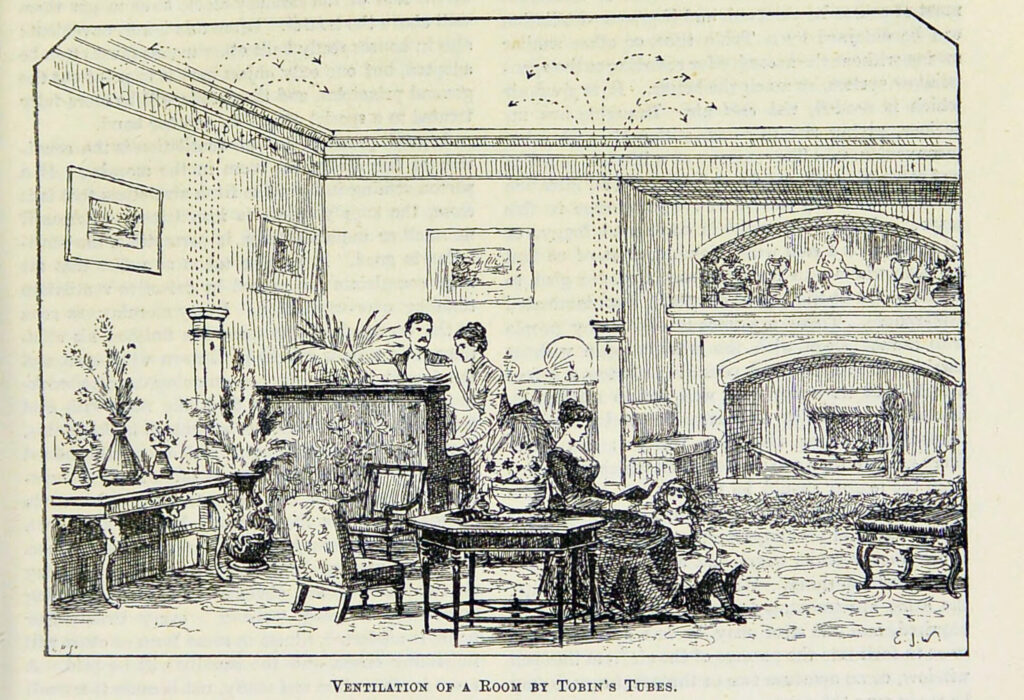

Tobin’s Tubes in operation (Anon 1890ish).

Times. 1875/04/12. Ventilation. London. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

VENTILATION.

The art of ventilating the confined spaces within which the inhabitants of civilized countries live and pursue their avocations is one which is universally admitted to be of high importance, but which has not hitherto been applied with commensurate success. There is much reason to believe that some of the most fatal maladies owe their origin chiefly, if not entirely, to the habitual breathing of vitiated air; and this seems to be especially true of consumption, which is about six times as frequent among those who lead sedentary lives as in those whoso occupations require then to be constantly out of doors, even in all seasons and weathers. Apart from the actual production of disease, it is a matter of daily experience that vitiated air, even that of a confined living or sleeping apartment, produces drowsiness, unfitness for active mental or bodily exertion, and often headache; and these evil effects are heightened when the air is contaminated not only by the respiration, and the exhalations of human beings, but also by the combustion of any of the substances which are used as sources of artificial light. Any one who has tried knows how much less fatiguing it is to address an audience in the open air than in the most spacious edifice; and any one who sleeps for the first time in a room with a widely-opened window will find that he will not only awake before his customary hour, but he will experience a feeling of being unusually refreshed by his repose. Notwithstanding these well-known facts, and notwithstanding the stress laid upon pure air by all sanitary reformers, the endeavours of architects to obtain the blessing have almost always made shipwreck upon the draughts which they have occasioned, and upon the lowering of temperature which they have caused. These endeavours, moreover, have generally been guided by the entirely erroneous assumption that vitiated air, being heated, would not only ascend, but would also escape through outlets in the upper part of a chamber. When such outlets are made, the heavier cold air descends through them, pushing aside that which is lighter and warmer, often forcing it back through presumed inlet openings, and coming down in a stream, like water poured out of a jug, upon the heads of any unfortunates beneath. So completely has scientific ventilation been at fault that nearly every contrivance for the purpose, when applied to inhabited rooms, has produced chill draughts which were more unpleasant, and even more immediately pernicious, than vitiated air itself, and has induced the dwellers to stop up the openings with the least possible delay. The lungs are soon rendered insensible, by custom, to the foulness of the air they breathe; but the surface of the body cannot be reconciled with equal readiness to the impact of cold air. The practical result has been that our houses, and especially our rooms used for public purposes, are not ventilated at all. To a person coming from the open air the atmosphere of even a spacious bedroom, which has been occupied during the night, is stuffy and unpleasant; and the atmosphere of any schoolroom, of any crowded church, or of any court of law, is well-nigh intolerable. This is the case even in the daytime, and, when evening brings the necessity for artificial illumination, the evils are increased in a threefold ratio.

The solution of all these difficulties, and the means of rendering the atmosphere of any chamber as pure as that outside the building, without improper lowering of temperature, and without the production of draught, has recently been discovered, and has been brought into practical application, by Mr. Tobin, a retired merchant, who lives in the neighbourhood of Leeds. Mr. Tobin’s own account of the matter is that he was once watching a current of water which flowed into a still pond. He observed that the moving water kept together, and held its own, until its course was arrested by the opposite bank, when it curved gently round on either side, and was lost insensibly in the general body, which had its outlet for overflow at one side. He reflected that a current of air introduced into a room would act in precisely the same manner, keeping together until it encountered an obstacle, then mixing insensibly with the air around it, and compelling an overflow wherever there was an opening available. He saw that, if this were so, it would only be necessary to give the entering current an ascending direction, so that it would reach the ceiling without impinging on any person, in order to solve the whole problem of domestic ventilation. Experiments at his own house confirmed his anticipations, and led him to contrive methods, which he has patented, of carrying his principle into practice. At that time the state of the Borough Police Court at Leeds was, as, indeed, it had been for some time previously, a source of great perplexity to the Town Council. The Court is one of a series of rooms which surrounds the Town-hall, and the doors opening into it are three in number – one leading from a corridor which gives access to the public, one leading into the magistrates’ retiring room, and one from the cells into the dock. Light is admitted only by a window in the roof, and in this skylight there is an opening, intended for the exit of foul air, but practically serving for the entrance of fresh air. The Court is liable to be crowded every morning by unclean visitors, and the heat and stench were such as to defy description. Through this heat and stench a stream of cold air fell down from above on the presiding magistrate, and occasioned him severe suffering. The Justices were often compelled to make their escape before the business of the day was concluded; and the Council had expended between £1,400 and £1,500 on successive ventilation doctors, each of whom had left matters as bad as, if not worse than, they were before. The subject was one of continual comment in the local papers, but the Council had begun to despair of a remedy, when Mr. Tobin offered to supply one. He suggested that the Council should pay him a nominal royalty for the use of his patent, and that they should pay the few pounds required for doing the work, leaving his own remuneration to their discretion when they saw the effect. These terms having been accepted, Mr. Tobin placed under the floor of the Court three horizontal shafts which communicated with the open air through a cellar grating. From these he brought eight vertical shafts through the floor at different points. These vertical shafts rise about four feet above the floor, and are each five inches in diameter. They have open mouths, and are placed out of the way in corners, or against the partitions of the Court. From each shaft there ascends to the ceiling an unbroken current of the outer air, like a fountain, or like a column of smoke when the barometer is high. The current will support feathers, or wool, or other light substances, and has so little tendency to spread laterally that it can be made to influence half the flame of a candle, while the other half remains undisturbed. A person resting his cheek against the margin of one of the tubes feels no draught, and the hand feels none until it is inclined over the orifice. Tho effect was instantly to render the Court as fresh and sweet as the external air around the building. The steady flow of the eight ascending currents constantly rinsed out, so to speak, the confined space, and washed away the effluvia of dirty people, and the products of respiration, as fast as they were liberated, forcing them out through the skylight opening which was previously only an inlet, but which was altered in a manner to facilitate egress. After three months’ trial, and after all the magistrates for the borough had joined in a report, which expressed their entire and unmixed satisfaction, the Corporation voted Mr. Tobin an honorarium of £250, to express their sense of the benefit which he had conferred upon the town. They also applied his system to the Council Chamber; and their example was followed by some of the leading bankers and merchants, by the churchwardens of St. George’s Church, and by the proprietors of the Leeds Mercury, who have had every room and office in their spacious premises ventilated under Mr. Tobin’s superintendence, and who have expressed, in two or three descriptive articles, the entire success which has been obtained.

The system of vertical tubes is necessary for rooms which have no side windows, or which have only a small window surface in proportion to their cubic contents. But Mr. Tobin at the same time contrived a cheap and simple method, by which vertically ascending air currents can be introduced through common window sashes; and this method will suffice for all ordinary living or sleeping apartments. Each of the openings made for this purpose is provided with a cover by which it can be closed at will; and they admit of a method of securing the sashes which affords almost entire security against burglars. A very competent authority has communicated to us his experience for eight weeks of a room containing 2,500 cubic feet, ventilated, under Mr. Tobin’s direction, by four window openings which have an aggregate area of 30 square inches, but which are filled by layers of cotton wool to filter the entering air from dirt and moisture. The currents ascend in absolute contact with the glass, keeping so closely to it that they do not affect the flame of a taper which is hold vertically in contact with the sash bar; although, as soon as the taper is inclined towards the pane its flame is strongly flattered. In this way the air ascends to the top of the window, where it is directed to the ceiling and lost as a current, being no longer traceable by taper, hand, or fragments of down, although closing the window openings diminishes in a marked manner the draught up the chimney. Each opening, as already described, has an independent cover, and, without the wool, the four would, in cold weather, be too much for a room of the size specified. With the wool they do not perceptibly diminish the temperature, but they give a feeling of absolute out-of-doors freshness, which must be experienced in order to be appreciated. There is no draught anywhere, and the openings are not visible unless sought for, so that curious inquirers who have remarked on the result have been unable to find the inlets. Arranged as described, the openings are sufficient to feed a large argand table gas burner, and to sweep away entirely the products of its combustion; so that, when the room has been shut up, with the gas lighted and with a good fire, for three or four hours, persons entering it from the open air are not able to discover, except by the greater warmth, any change of atmosphere. A bed-room ventilated in a similar manner is as fresh when the door is opened in the morning as when it was closed at night.

Mr. Tobin’s experiments early led him to the conclusion that the prevailing notions about tho necessity for carefully planned outlets were fallacious, and that, if proper inlets are provided, the outlets may generally be left to take care of themselves. In order to test this he fitted two vertical tubes into a small room which had a fire-place and a three-light gas pendant. He closed the opening of the fire-place, and every other opening into the room except the tubes, hermetically, and, shutting himself within, pasted slips of paper all round the door. He found that there was then no entrance current by the tubes. The room had no outlet; it was full of air, which his respiration had not had time to consume in any appreciable quantity, and no more could get in. He next lighted the three gas burners, and a steady entrance current immediately set in through the tubes, and continued as long as the gas was burning. He waited nearly an hour without any deterioration of the atmosphere becoming perceptible to his senses, and with the currents steadily coming in and ascending in their customary manner. He then cut through the paper which secured the door, and left the room, shutting the door behind him. Returning half an hour later, he found the atmosphere still fresh. He next extinguished the gas, and the currents gradually died away, the original state of equilibrium or fullness being restored. This experiment, which has been several times repeated, seems to show that the external air will enter just in proportion as room is made for it by combustion or respiration, and that the rate of supply is essentially governed by the rato of destruction or demand. In the closed room the water produced by combustion would probably be condensed, and the heavy carbonic acid would sink to the floor. If the combustion continued indefinitely, tho accumulation of these products would in time render the air “irrespirable;” but that time would be much longer in coming than is generally supposed, and, for all practical purposes, the chimney throat is everywhere sufficient as an outlet.

The rationale of the matter appears to be that when tho external air communicates with that of a room through a channel which terminates in a vertical shaft, an inward current is produced as soon as the air of the room is either rarified by warmth or partially consumed by respiration or combustion. This inward current is due to the pressure of the external atmosphere, which is capable of driving the entering air, in a compact column, to a considerable elevation. The whole pressure of the atmosphere is equal to rather moro than 14lb. on each square inch; and this force would be all exerted if the chamber into which tho air was to be driven was itself a vacuum. As it is, the pressure exerted will always be determined by the difference between the atmospheric density within and without the chamber; and hence, the more the internal air is rarefied or consumed, tho greater will be the force of the entering current. It follows that the supply of air adjusts itself automatically to the deinand, and that the inlets should always be sufficient for the maximum requirements of the room to which they are applied. However large they may be, they will not admit air in excess of the rarefaction or combustion of that which is already there; and, as rarefaction and combustion diminish, the number of cubic feet passing through the inlets in a given time will diminish in precisely the same ratio.

In order to obtain an absolutely perfect result it is necessary to bear in mind that the behaviour of the entering current will be precisely like that of the vertical column of water sent up by a fountain, except that, as the ascending air is received in a fluid of only little less density than its own, it will mingle with that fluid gradually when the propulsive force is exhausted, instead of falling almost vertically by the action of gravity. But just as a fountain, if it encountered an obstacle while its column was still compact, would rebound from that obstacle with considerable violence, so the entering current of air, if it meet with an impediment prematurely, will be reflected as a draught. We have seen this very well exemplified in a room at Leeds, in which the construction of the windows rendered it necessary to make the inlets much higher up than usual, and in which, when the force of the entrance current was increased by lighting gas, a very distinct stream of cold air was reflected from the ceiling. To prevent such an occurrence, it is necessary to make the inlets so low down that, under all ordinary circumstances, the force of the stream will be expended before the ceiling is reached; and when, from any circumstances, this cannot be done, the current may be broken by strainers of wire gauze or other suitable material. In this, as in most other matters, some special adaptation of means to ends is required; and the arrangements for any given room must be planned by some one who has practical knowledge of the subject.

Within the last two or three weeks Mr. Tobin has adapted his system to the Liverpool Police Court, and there, as well as at Leeds, he has entirely succeeded in attaining his object. The conditions were much the same as those at Leeds, and everybody frequenting the court, from Mr. Raffles, the stipendiary magistrate, to the gaolers, has borne emphatic testimony to the change which has been wrought. Mr. Raffles, speaking from the bench, is reported by the local papers as saying that at the end of the day he did not feel half so tired and exhausted a previously; and the satisfaction given to the local authorities has been such that it has been determined that all the other courts in the Town-hall shall at once be ventilated in a similar manner. In London the method of ventilation by vertical tubes has been applied to one of the wards of St. George’s Hospital, and that by window openings to the Council Chamber of the Society of Arts and to a few private houses, everywhere with the same excellent results. The discovery that the pressure of the atmosphere can thus be utilized as a perpetual source of air-supply without the aid of fans or other mechanical contrivances; the discovery that all draughts can bu obviated by the employment of vertical entrance channels, provided only that their mouths are not too near the ceiling, and the discovery that improper lowering of temperature is prevented by the circumstance that the rate of entrance of air is governed by the demand, are truly comparable in their simplicity to the balancing of the egg by Columbus. Simple as they are, they are none the less calculated to add greatly to the public health and comfort. Their very simplicity implies a cheapness which places Mr. Tobin’s contrivances within the reach of every householder; and some one of these contrivances will be found applicable to every enclosed space within which human beings congregate. They would at once overcome the difficulty which has been experienced in introducing fresh air into some of the rooms in the British Museum; and in the dwellings of the poor they would obviate most of the merely sanitary evils of overcrowding. There ought not, in the course of another twelvemonth, to be a single “stuffy” sitting-room, bed-room, church, school-room, law-court, or theatre in the country. The entrance currents, whether obtained by shafts or by window openings, are entirely uninfluenced by rain or wind, and admit neither; and the only counter-balancing disadvantage attending the system is that the use of a room ventilated by either method is followed by a very speedy intolerance of the ordinary atmosphere of domestic interiors.

Comment

Comment

The Commissioners of Patents’ Journal records the seal on 1873/09/16 for:

1081 MARTIN TOBIN, of Leeds, in the county of York, Gentleman, for an invention of “An improved means or mode of ventilating rooms or apartments and in the apparatus employed therefor.” Dated 24th March, 1873. (Patent Office 1873/09/16)

I can’t find the volume for the first half of 1873.

John Whitehurst came to similar conclusions in the late 18th century (Whitehurst 1794).

I am sure that the devil was in the detail, but how good were Tobin’s Tubes really?

The Tobin tube (a vertical shaft, open at the top, and communicating with the outside at the base) was popular in Victorian times (c 1878). One such had a water trough at the base of the shaft, ostensibly to trap dust from the incoming air. The Tobin tube was not a success and, shortly after its introduction, Edwards stated flatly that either the free area was too small or the incoming air immediately spilled over the top onto the floor. Worse, the provision of lids meant that all too often they were permanently closed. Yet the Tobin tube remained in use for 30 years or more, and was even recommended by an early 20th century architect.

[…]

In 1894, Professor Jacob, a pathologist, held the architect in contempt:

In most cases architects are content to introduce an occasional air brick or a patented device called a “ventilator” … Real ventilation is so uncommon that the architect usually thinks this object has been attained if some of the windows can be opened. Some think that the presence of “ventilators”, especially if they have long names and are secured by Her Majesty’s letters patent, ensures the required end. We may as well supply our house with water by making the trap door in the roof to admit rain.

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

13 February 1896: Now connected to mains electricity from the Whitehall Road power station, Leeds City Council sells off the town hall’s (coal-fired) generation and storage plant

13 February 1896: Now connected to mains electricity from the Whitehall Road power station, Leeds City Council sells off the town hall’s (coal-fired) generation and storage plant

Comment

Comment

The Leeds Mercury commented immediately on the increased productivity caused by Hirst’s innovation:

The simple, principle of this improvement is, that he doubles the number of spindles in the mule, by putting two rows instead of one. The machine invented by Mr. Cartwright contained double the number of spindles in Sir Rd. Arkwright’s jenny, and Mr. Hirst’s machine therefore contains four times that number. Yet it is surprising that the old jenny is still used in most of the manufactories in this neighbourhood… Mr. Hirst has now a machine all ready for working, containing four hundred spindles, whereas the machines commonly used in this neighbourhood have not more than eighty or ninety. (Leeds Mercury 1825/01/22)

Hirst appended two testimonials to this effect to a letter three months later to the Mercury:

Leeds, April 29, 1825

Hurst’s and Heycock have milled two olive [?] pieces for Messrs. Pawson and Smith, of Farnley, in two days, which would have taken thein four days at their own mill; and their miller declares, they are better milled than they could have done them at their own place. Their miller was with them all the time, and asserts this himself.

(Signed) JONATHAN ROBERTSHAW, Miller to Messrs. Pawson and Smith.

Messrs. John Edwards and Sons, of Pye-nest, near Halifax, also sent two pieces of white Cassimeres to be milled. Their miller stayed till they were done, which was in seven hours, and says, that they would have taken from 12 to 13 hours at home.

(Signed) WM. KITCHIN,

Miller to Messrs. John Edwards and Sons, Pye-Nest.

(Leeds Mercury 1825/04/30)

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter