21 March 1880: The surgeon Thomas Pridgin Teale tells Leeds fathers to get involved in their children’s early years

Leeds Mercury. 1880/03/27. Fathers and Their Children. Leeds. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

FATHERS AND THEIR CHILDREN. A Lecture and a Conversation.

The last preceding lecture for the people, reported in these columns, was delivered by a well-known physician, the place of meeting being the Church Institute, and tho time a Sunday afternoon. In the same hall, last Sunday, a surgeon of widely acknowledged skill was the speaker. It was appropriate that Mr. T. Pridgin Teale should follow Dr. Clifford Allbutt, and tho sequence may not have been accidental; but it was clearly not a matter of arrangement that the themes selected supplemented each other. In dealing with “Social Instincts,” Dr. Allbutt showed how certain conditions of existence benefit communities; it was Mr. Teale’s object to make plain the laws under which the individual himself may receive the training which is necessary for his well-being. The one spoke of impulses for good or evil amongst men in the mass; the other of the influences which are at work in the family to elevate or degrade children. The sentence “Spoiling the child is self-indulgence under an alias,” taken from the work “Guesses at Truth,” was the text on which for about an hour Mr. Teale talked in a simple, convincing, conversational way to his hearers, of whom there were many.

The lecture had been advertised as specially intended for men. Surely it ought to have been for mothers. Mr. Teale, anticipating this, remarked at the outset that if anything he said was worth consideration at all, no doubt it would reach the ears of the mothers through the fathers; but at the same time he thought it would be found that the inquiry would be of a nature to justify special application to those who are fathers. He did not propose to say much as to how children should be trained, that being far too wide and serious a subject to be treated properly in a conversational lecture; his aim was rather to direct attention to some points in the want of training in children, to which many of the sins and errors and misfortunes of after life may be traced. It was well, then, for the father to pause and inquire whether he was doing as much as he ought to do, and could do, to help his wife in the proper up-bringing of boys and girls. There is a very old saying, “The boy is father to the man.” There is another common saying that the education of a child begins the very day that he is born.” The sacred poet puts it, “Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it.” Are all these maxims, asked the lecturer, well thought of and acted upon by husbands and fathers? Is it not rather a fact that many a father thinks that all responsibility for the training of his children rests upon his wife – the training in babyhood, the training in childhood? And when at last the children arrive at teenhood, and the father thinks they must come under his influence and authority, it is found, alas! that they are untrained, or perhaps what is worse, mistrained, and that it is too late to begin to impose either influence or authority. If it is borne in mind that the training of the child in good or bad habits begins as it were with its birth, a great many difficulties will be obviated. People say, “It is no use checking a child; poor thing, it knows no better; it will be time enough when it gets older.” No; check it at the very beginning. There is a Latin saying in reference to ills of all kinds – principiis obsta – stand out against them, put your foot upon them at the very outset. The character of most children is formed before they are three years old, or when they are about three years old. If you have a child thoroughly obedient, not through fear, but through training, at three years old, and it is not subjected to very unfortunate circumstances, the probability is that that child will grow up in obedience; and obedience in childhood is, in a great measure, the basis of all the rest. A child should not be allowed to get into little bits of bad ways. It can be taught to keep quiet, and it can be taught self-control. Every time a child is not checked for doing things or attempting to do things it ought not to do, a valuable lesson in self-control is withheld from it; and it is from the want of self-control that so many ills come upon man in after life. Indulging a child, spoiling it, is unfortunately the result of very warm attachment, but it is none the less a great cruelty and a great wrong. When a child is ill, just as when a grown person is ill, tho weak points in the character come out very prominently; and are very noticeable to the medical man. A child badly brought up will, when sick, often throw itself into a state of great irritation, and so act that often nothing can be done for it until it is first sent to sleep under the influence of ether or chloroform. A child well brought up will, on the other hand, submit generally with great patience and quietness to the treatment that is pre. scribed. But sad to say, the spoiled child is very often worse spoiled when it is sick; it is so petted when it is ill, that when it gets better its management becomes a very serious matter. A child in illness needs training as much as it does when in health. Carry the matter a little further. The child who is not trained in self-control goes to school. He is disobedient in some things, he gets into disgrace, he loses some of his self-respect, and very often from a start like this he is led into bad courses when he might so very easily have been guided in a different direction. Then when the boy or girl is untrained from infancy in habits of self-control, how difficult it is – how impossible in many cases – to avoid the temptations that are then 80 numerous! Allow a child to grow up greedy in the matter of food, and it is only a little step further when it will be greedy about taking wine and beer, and then the tendency is, through want of self-control, to drunkenness. And what can be done then? At the time people begin to deal with drunkenness, the drunkard is practically insane from disease. You want to prevent the disease. The energies of modern medicine are being turned into what may be called preventive channels, and in the same way the efforts of social reformers may with advantage be turned in the direction of what may be described as preventive temperance. The lecturer expressed a strong conviction that a great deal of drunkenness may be traced back to want of training by the parents of their children in self-control, and very much of it to the habit of spoiling children. Aud the suffering of females in this respect is even worse than in the case of males; and for this reason, that females are more liablo as they grow up to fluctuations of health, which have a tendency to make them seek stimulants unless the habit of self-control has become natural with them from their earliest years. In the case of children stimulants must be considered as medicine, to be prescribed by a doctor and to be stopped by a doctor as 60011 as they havo done their work. But there are other benefits to be gained from these very early lessons in self-control than those referred to. The girl brought up in the habits of self-control is not likely when she goes out into the world, say as a servant, the moment anything happens she does not like, to lose her temper and throw up her situation. A spoiled girl has a poor chance of becoming a good servant, and a very poor chance indeed of making a good wife and mother. The spirit of unselfishness – the giving way to others, the loving, helpful, considerate disposition – should also be taught from infancy, and although temperaments differ, and what may be done in one case cannot be done in another, this is not usually a difficult lesson to inculcate. All this leads up to good breeding, and good breeding means a great deal. The spoiled child can hardly become a true lady or a truc gentleman, for good breeding is that self-control, that self-denial, that courteous behaviour, that thoughtfulness for others which the untrained child, with ideas of self paramount, knows nothing of. In speaking of the proper care of children, the question of punishment asserts itself. It is said in Holy Writ, “Spare the rod and spoil the child.” But the rod must be used with extreme caution. It may do as much harm as good, and more harm; and the lecturer’s opinion was this – that the rod must be used very early, before the child has reason enough to obey from judgment. The advantage of a little corporal punishment is that the child may know you mean what you say. Once let a child know, by a little corporal punishment, that you mean what you say – and in most instances it need not be done more than once or twice – and you have gone a long way in the training of that child. When the child gets older, corporal punishment is more often an injury than a benefit – he begins to suspect his parent of punishing him in anger; and that is ruinous. Such is a brief outline of Mr. Teale’s address. The lecture was followed by a very interesting series of questions and answers.. The first proposition from the audience seemed to foreshadow a controversy on the temperance question, and it was not thought desirable,. therefore, to enter into it. To all the other queries replies were given, as reported below.

“At what age, Mr. Teale, would you recommend the cessation of corporal punishment?”

“I do not know,” was the response, “that I am justified in putting it so definitely; but if you will only take it as a kind of impression, I think the less after three the better, and very little after six. I look upon corporal punishment as simply a means of enforcing upon the child that which it cannot otherwise understand the necessity of obedience. Get a child to be obedient, and there is no necessity for corporal punishment.”

“But I should like to ask,” came the next question, “whether it is not possible to do entirely without corporal punishment. I sometimes inflict corporal punishment, and I find I can never inflict it without feeling somewhat angry. I can never get that length with a child without feeling somewhat… What I mean to say is, that I cannot do it in cold blood, if you understand me better that way.”

“Herein,” said Mr. Teale, “comes in the consideration of the fact that one rule won’t do for every person. Do not take it that every child will require corporal punishment, or that every child can be equally easily trained. Children differ from one another in families, and different dispositions must be taken into consideration. In referring to the application of corporal punishment, I have only spoken broadly.”

“I would like to ask if the lecturer thinks it possible to prevent a child from crying or speaking aloud, unless from ailments, by the time it reaches its first year?”

“Well, I do not think you can entirely, but I am sure a great deal of training may take place before the child is a year old. What I want to point out is, that the bad habit must not be passed over with the idea that it will be all right when the child is a little older. child must not be allowed to pull and tumble things about when it might just as well be told not to do it, and when it can be trained not to do it.”

“Don’t you think,” said another questioner, “that we must expect a child of mercurial temperament – a naturally restless child – to be less easily dealt with or to be differently dealt with than one whose disposition is apathetic”

“I quite agree with that,” Mr. Teale made answer; “the parent must study these points. He must not think that every thing is ready to hand. He must remember that he cannot keep his children on a straight line with a ruler, as it were, and get them to do exactly as he wants them.”

“What should you recommend in the case of children who are very self-willed, and can scarcely be brought to do what they are told-up to the age, say, of about three?”

“I believe that in many of these cases-recognising that the children are constitutionally, apart from want of training, more restless and self-willed than others-what is needed is patience. Parents should remember that time does a great deal. Oue child may be fairly trained when it reaches its third year; while another may take till five to arrive at the same standard of self-control. The question is a very important one. You cannot always get the thing done in the time you would like. You are dealing with very sensitive material, and you must allow time as an element a very considerable element-in attaining the object you have in view.”

It seems to me, sir,” said another person, “that an important phase of this inquiry has not been touched upon. That is the feeding of children. Reference has been made to restlessness, to fidgetty children, and it has been said or implied that this may be overcome by training. Is it not a fact that restlessness arises sometimes from over-feeding, and that it may in such cases be overcome by attention to diet? I should like also to ask whether it is well to give children animal food?”

“These,” replied the lecturer, “are also very important points. Many infants are restless and fretful because the feeding is not a matter of care. It is a great temptation to a mother when her child cries to quieten it by giving it more food-by giving it the bottle. They keep doing this until the child’s digestion is affected, and it is a very long time before it can be got right again. This is where self-control on the part of the mother should come in. Then about animal food. A mistake is sometimes made in giving young children, when they have teeth, too too much meat to eat. The more common error is in giving too much instead of too little. I have often seen a child looking pale and thin and pasty, and his parents say, ‘Oh, he eats very heartily; he eats more meat than so-and-so; and I have said, ‘Well, give meat only every other day. I have known the child under these circumstances begin to improve at once.”

“What kind of food should a young child have, say during the first three months of its existence?”

“I suppose that means what kind of food should it not get?”

“Just that.”

“Well, if it does not get the food which its mother should have for it, it ought to have milk, unless a doctor has reason to order otherwise-nothing but milk. The only natural food for a child up to the weaning period is pure milk, and especially the mother’s milk.”

The form in which the last question was put caused a ripple of amusement among the audience and the Vicar of Leeds (who was in the chair) thought this question and the answer might vary fairly be supposed to exhaust the inquiry. In thanking Mr. Teale for his lecture, he took the opportunity of remarking that if parents would only encourage their children to put confidence in them at an age when boys and girls are upt to go into bad ways-say from fourteen to eighteen-temptations would be more casily avoided. Once a boy felt that he had a father to whom he could tell everything, there was very little fear for the lad.

In a closing sentence, Mr. Teale said it was important that parents should remember that children are very observant and readily trace motives. “As soon as a child can speak-probably before it can speak-you need to be as cautious as possible in its presence of what you do and what you say.”

Comment

Comment

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

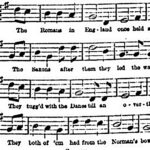

25 September 1880: Thomas Harper reveals to the Leeds Mercury’s young readers a mnemonic song of monarchs (except Oliver) used in the village school at Weldrake (York) in the 1770s

25 September 1880: Thomas Harper reveals to the Leeds Mercury’s young readers a mnemonic song of monarchs (except Oliver) used in the village school at Weldrake (York) in the 1770s

Comment

Comment

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter