23 May 1889: The poet Edward Carpenter recalls walking into the polluted hell that is Sheffield and finding steel producer Charles Wardlow curiously engaged

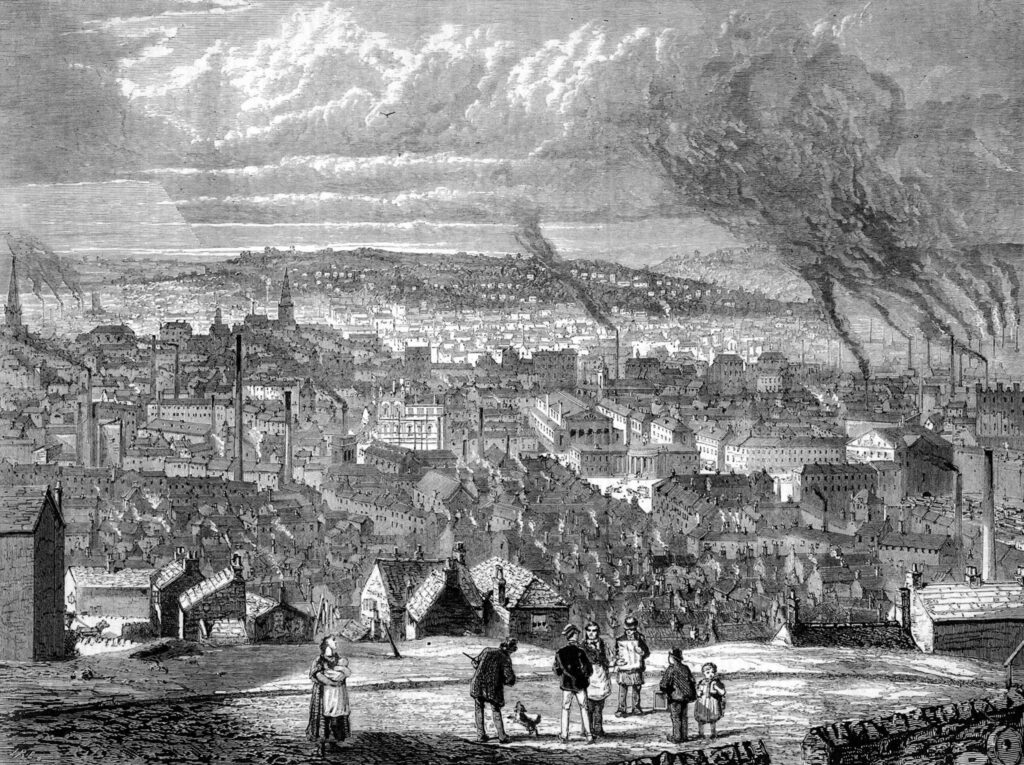

Sheffield looking east from St John’s Church circa 1874, with factories filling the sky with smoke (Anon 1874ish).

Edward Carpenter. 1889/05/25. Smoky Sheffield. Sheffield Independent. Sheffield. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

CORRESPONDENCE.

“SMOKY SHEFFIELD.”

TO THE EDITOR. – I have lived near Sheffield for some time, and have often, like other people, thought it ten thousand pities that the fine scenery in its neighbourhood and even the town itself-whose site is one of the best in England-should be defiled by the masses of smoke which make Sheffield a byword I fear throughout the civilised world. Knowing, however, what an enlightened population we have in this town, and the general intelligence and public spirit of its municipal bodies, I have always felt sure that a very few years would see a great change in this respect, and that by the adoption of some of the modern furnace improvements and the creation of new bye-laws, as well as the enforcement of the old ones on the subject, our chimneys would cease to emit the volumes of soot which now warn every casual railway passenger not to stop here if he can possibly help it.

Some weeks ago, as I came over the hills-it being a still day-I had an opportunity of witnessing the full effect of the smoke nuisance. Sheffield itself-except a few outlying villas-was invisible; the very land on which it stands was blotted out; only a vast dense cloud, so thick that I wondered how any human being could support life in it, went up to heaven like the smoke from a great altar. An altar, indeed, it seemed to me, whereon thousands of lives were being yearly sacrificed. Beside me on the hills the sun was shining, the larks were singing; but down there a hundred thousand grown people, let alone children, were struggling for a little sun and air, toiling, moiling, living a life of suffocation, dying (as the sanitary reports only too clearly show) of diseases caused by foul air and want of light-all for what? To make a few people rich! And this was not a lunatic asylum! I descended into the smoke. The sun went out; the chimneys towered round me, belching forth thick volumes. What did I find? Ah, the irony of it! I found an agitation going on against tobacco! I found Mr. Wardlow-whose chimneys have blasted half the oaks on Wharncliffe side, and blasted, too, I fear, scores of those far more delicate and sensitive air-trees which grow within the lungs of Sheffielders-I found Mr. Wardlow presiding over a league to put out my pipe! Dear Mr. Wardlow, if all the tobacco smokers in the world were congregated together in one place, I doubt whether they could make as much smoke as you do out of one of your chimneys.

Living, as I do, out in the country, I know something of the injury which one chimney may do. (The inhabitant of Sheffield does not notice one chimney any more than the dweller in a London lodging notices one flea.) I sometimes see the smoke from a single chimney travelling in a straight line for three or four miles over the country, befouling the air, darkening the sun, and damaging the vegetation as it goes. As the wind changes, the evil blight sweeps round. The birds cease to sing, the crops are only half grown. Ten square miles of country are sacrificed in order that one manufacturer may economise the little extra expense and trouble which smoke-consumption would involve. But is this really economy? is it wisdom? is it good sense? is it common sense? is it any sense at all? Now I understand why it is that in the middle of Sheffield not even a plant will grow in a house window, not a tree in the street. A foreigner, walking with me in the town one day, said, “Well, I never was in a place before where the dirt hit you in the face!” And if the very plants will not grow here, is it to be expected that our children, that our babes, can thrive, and grow up healthy men and women? Why, sir, I find in our Sanitary Officer’s Report (for 1885), to which I have already alluded, that a quarter of all the deaths in Sheffield are due to diseases of the respiratory organs-an enormous percentage. Another large percentage is due to diseases of the nervous system-greatly no doubt arising from the want of sunlight-and these two items in the death-rate far exceed any other items down the whole list. This being the case, is it not worse than folly, is it not sheer wickedness, to go on as we are doing?

But what is to be done? Does not our Town Council send forth a smoke inspector every year, and does he not return with a report saying that “all is well ?” I read the report (for 1885): “Number of smoke nuisances abated, 113; number partly abated (I wonder what that means), 14; number unabated, 15.” I wish I lived in the year 1885, when there were only 15 smoke nuisances unabated! How pleasant it all sounds! Like Balaam, our inspector is sent forth to curse, and he blesses (the manufacturers) in the pleasantest possible way. “The best of all possible worlds, my friends for those who live out of the smoke-everything is just as it should be, and there is no necessity for you to spend a farthing out of your profits in order to diminish the mortality of the wretched beings who produce those profits for you.” Jack Wheelswarf, is it not time that you woke up, and attended to this matter yourself? Once I know you used to scratch your stupid old head and think because a good smoak was a sign of good trade, that therefore you couldn’t have good trade without a good smoak. But I guess you don’t think that now. The city of Lyons, which has immense manufactories, is, as 1 understand, almost quite free from smoke-because, well I don’t like to say the people are sensible there, but they are up to the times. To-day, with all our scientific inventions, there is not much doubt that we can cleanse ourselves from this nuisance-the only doubt is whether we care to. If the workers of Sheffield were negro slaves, I suppose their masters would consider it their interest not to poison them; but now … however, I forbear to draw the conclusion. I wish, Mr. Editor (if you are not very tired of doing so), that you would try once more to rouse the slumbering consciences of our town authorities and of those whose riches have come by smoke to a sense of their heavy responsibility in this important matter.

I am, sir, yours faithfully,

EDWARD CARPENTER.

Holmesfield, 23rd May.

Comment

Comment

The inaugural meeting of the Sheffield Anti-Tobacco League was held on 29 April:

A meeting to inaugurate the formation of an anti-tobacco league for Sheffield and district was held last evening at the Temperance Hall. There was a thin attendance, numbering 40 or 50 people. Mr. C. Wardlow (president) was in the chair, and was supported by the Rev. T. Whittaker (president of the Primitive Methodist Conference), the Rev. J. Calvert, Mr. G. W. Langley (hon. sec), Mr. D. T. Ingham, Mr. John Parker, Mr. A. S. O. Birch, Mr. T. L. Green, Mr. W. H. Hill (Rotherham), Mr. T. Wigfiold (Rotherham), Mr. John Bradley, and Mr. S. Hoyland.,The Secretary read letters of apology from the Mayor (Ald. Clegg), the Rev. S. Chorlton, Mr. E. S. Bramwell, Mr. C. H. Wilson, Mr. A. Neal, Mr. G. H. Hovey (who said while excessive smoking was highly injurious, in its moderate use it was a weak and childish amusement, unworthy of men), the Rev. J Slater, the Rev. G. Turner, Mr. C. T. Skelton, tho Rev. T. Allen, and Mr. Edwin Richmond (Sheffield Independent 1889/04/30)

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

Comment

Comment

Shirley is set in 1811 and 1812, and Luddism became a serious threat in the West Riding in early 1812. Easter Sunday was 29 March that year, so Whit Tuesday was 19 May – although Charlotte Brontë’s imagination, perhaps inspired by weather reports in the Leeds Mercury, which she consulted extensively, locates it in the last week of May. John Lock and Canon W.T. Dixon say (p.63) that the scene reworks a confrontation between Patrick Brontë and a drunk when he led the Whitsun procession in Dewsbury in 1810 (Lock 1965), but Herbert Wroot (p.78) has found in the Dewsbury Reporter of 12 December 1896 the report of an interview conducted by P.F. Lee in which the Rev. James Chesterton Bradley, the original of “Mr. Sweeting,” says that Charlotte Brontë reused more or less literally an actual episode:

At the head of the steep main street of Haworth is a narrow lane, which on a certain Whitsuntide was the scene of a similar event to the one related in this seventeenth chapter of ‘Shirley.’ The Church School procession had defiled into the lane, ‘had gained the middle of it,’ when ‘lo and behold! another – an opposition procession’ – was entering the other end of the lane at the same time, ‘headed also by men in black.’

It was interesting, Mr. Lee went on to say, “to hear from Mr. Bradley how Patrick Bronté, seeing the situation, at once assumed the offensive, and charging the enemy with his forces soon cleared the way.”

Wroot also says that “immediately upon the publication of the novel, Briarfield was identified, by all acquainted with the district, as Birstall” (Wroot 1966).

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter