2 October 1800: Part of an obituary to Harry Rowe, Punch and Judy man, trumpeter at the Battle of Culloden and the York assizes, who died today, old and ill, in the York poorhouse

Harry Rowe, doing his best to develop the exaggerated nose and chin of Mr. Punch: “In plain English I am master of a puppet show” (Anon 1806).

S.B. 1800/10. Some Account of Harry Rowe, the York Trumpeter. Monthly Mirror, Vol. 10. London. Get it:

.Excerpt

In the year 1797 he published at York an edition of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, “with notes and emendations” by himself, and embellished with his portrait. A second edition of this work appeared in 1799. His reason for this publication he relates in the preface: “I am master of a puppet-show; and as, from the nature of my employment, I am obliged to have a few stock-plays ready for representation whenever I am accidentally visited by a select party of ladies and gentlemen, I have added that tragedy of Macbeth to my green-room collection. The alterations that I have made in this play are warranted from a careful perusal of a very old manuscript in the possession of my prompter, one of whose ancestors, by the mother’s side, was rush-spreader and candle-snuffer at the Globe play-house, as appears from the following memorandum on a blank page of the manuscript: ‘This day, March the fourth, 1598, received the sum of seven shillings and four-pence, for six bundles of rushes and two pair of brass snuffers.’”

Comment

Comment

This image is preferable, but the BM’s lawyers are unlikely to drop their illegitimate copyright claims.

I guess George Speaight had a source for his description of Rowe’s puppet shows:

Rowe now heard that a widow, who was the proprietor of a puppet show, wanted an assistant to travel with it from town to town, and he obtained the position. He is said to have displayed great skill in manipulating the puppets, which were dressed in an expensive and elaborate style. On arriving at a town he would hire a large room in a well-to-do working-class district, and distribute a few hundred small handbills giving details of the programmes. At the door would be placed a large oil-lamp with two spouts, which gave a bright light as well as a most offensive smell, and the interior of the room would be lit by tin candlesticks, shaped to hang from nails in the wall. There would be candle footlights in front of the drop-curtain, and an orchestra of one or two violins. The programme usually consisted of a tragedy and farce, between which there would always be a short concert. Among his most popular songs were the sentimental “The Rose of Allendale” and a comic ballad known as “Chorus Tommy.” Ordinary performances took fully two hours, but at fairs the time was cut to twenty or thirty minutes; the whole show is said to have been very amusing, and to have made good use of local jokes. His mistress spoke for and worked the female puppets, he the male, and they did the entire show with one assistant. Before the performance Harry Rowe would stand outside inviting people in, and his mistress took the money; admission was a penny and threepence.

After a time they decided that it would be more profitable to work a regular circuit than to travel without any settled system, and they set upon York as their centre, visiting the surrounding market towns, such as Malton, Thirsk, and Tadcaster. The boxes of puppets were probably transported by carrier cart or perhaps pulled by a string of dogs. Harry Rowe eventually married the proprietress, and continued master of the puppets till his wife’s death in 1796. Shortly after this he sold the show, and retired to York. He is said to have made money easily during his career, but to have spent it freely, and in 1798 he entered the city workhouse, where he died in the next year at the age of seventy-four (Speaight 1955).

Speaight generously considers that there is some truth in the picaresque post-mortem “memoirs” attributed to John Croft (of which I suppose Rowe might have contributed top and tail) (Croft 1806). The rare book seller Bernard Quaritch provides a summary:

Apprenticed to a stocking-weaver, Rowe was dismissed for an ‘improper connexion with one of the maid servants’ and volunteered for the Duke of Kingston’s light horse in the year of the ’45 rebellion. He rose to the position of trumpeter, ‘behaved with great gallantry’ at Culloden, and when the unit was disbanded set off for London. Dismissed, for theft, from a position as ‘door-keeper and “groaner”’ to Orator Henley, he fell in with a crooked chemist (Van Gropen) and a quack (Dr. Wax – who reappears in ‘The Sham Doctor’) for whom he played the role of professional patient: ‘in the course of six months, he had been nine times cured of a dropsy’.

His next venture was a ‘wedding-shop’ in Coventry, a sort of matchmaking agency under the name of Thomas Tack. After ‘Mrs Tack’s’ death he quickly married the widow of a puppet-showman, and toured with her show all over the north, based at York, where he was also trumpeter to the High Sheriffs. During his life-time two dramatic works were published under his name: No Cure no Pay (1794) (see previous), and an edition of Macbeth (1797) interlarded with Shakespearean commentary by Rowe’s puppets, satirising the editions of Johnson, Steevens and Malone.

Much of the Memoirs (pp. 11-43) is taken up by cod letters written to Mr. Tack by singletons in search of a partner: a ‘giddy girl of sixteen’ seeks ‘a captain as soon as possible … for at present I lead a life no better than my aunt’s squirrel’; Dorothy Grizzle complains that the sea captain she was matched with has false eyebrows, false teeth, a glass eye, a wooden arm and a cork leg; the lady of Bondfield manor writes claiming droit du seigneur over all his matches, etc.

The Memoirs were published in aid of the York Dispensary, where Dr. Alexander Hunter (d.1809) had been physician since it began in 1788 (Bernard Quaritch 2021).

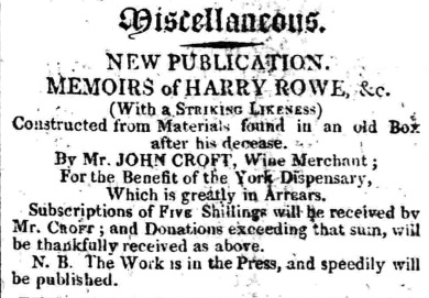

The ad in the York Herald, July 5, 1806, suggests that all was not well with Dr. Hunter:

While in the York Herald, November 15, 1806, Croft was helping Mrs. Rowe, despite, pace Speaight, her having died ten years before:

Mr. John Croft has given this week part of the produce of the subscription, arising from the Memoirs of Harry Rowe, to his widow, Mrs. Rowe, who is an object of great charity, being stone blind.

Not even Speaight seems to think that Rowe edited Macbeth, e.g. “If we mistake not, however, this was in reality the work of an eminent physician at York” (European Magazine 1800) – Dr. Alexander Hunter, editor of Evelyn, and physician at the York Dispensary from its foundation in 1788. However, a comparison of its style and that of the biographical intro credited (perhaps accurately, given the earlier, perhaps pre-senescence, date) to Rowe for wine merchant John Croft’s Select collection of the beauties of Shakspeare (Shakespeare 1792) suggests to me that the emendations to Macbeth may actually have been the work of Rowe.

More of the Macbeth preface, attributed to Rowe, and dated 30 May 1799:

I have the vanity to say, that for these thirty years past, I have honourably filled the office of trumpet-major to the high sheriffs of Yorkshire; and during that long period, I have ushered into the castle of York no less than ninety judges, all learned in the law. Yet, notwithstanding the emoluments of my high office, I was, six months ago, as poor as the poorest felon that ever was hanged at Tyburn; and, had it not been for the kind interference of a few friends, I must have died of want, in which case, the world would have lost an able commentator, and my benefactors a grateful friend. Critics may call me an impudent fellow, if they please, and my associates a parcel of blockheads; but I would have those learned gentlemen to know, that what we want in genius, we make up in solidity (Shakespeare 1799).

Something to say? Get in touch

Original

This well-known genius was born at York, in the year 1726. He was a trumpeter to the duke of Kingston’s light horse, at the battle of Culloden, in the year 1746, and attended the high sheriffs of Yorkshire, as a trumpeter, at the assizes, upwards of forty-six years. He was the master of a puppet-show, and, for many successive years, opened his little theatre in that city, during the summer seasons, and attended his artificial comedians to various other parts of the kingdom, during the course of the winter.

In the year 1797 he published, at York, an edition of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, 12mo. “with notes and emendations,” by himself, and embellished with his portrait: a second edition of this work appeared in 1799, 8vo.

His reason for this publication, he relates in the preface; the following are his words:

I am master of a puppet-show; and as, from the nature of my employment, I am obliged to have a few stock-plays ready for representation, whenever I am accidentally visited by a select party of ladies and gentlemen, I have added that tragedy of Macbeth to my green-room collection. The alterations that I have made in this play are warranted, from a careful perusal of a very old manuscript, in the possession of my prompter, one of whose ancestors, by the mother’s side, was rush-spreader and candle-snuffer, at the Globe play-house, as appears from the following memorandum, on a blank page of the manuscript:

“This day, March the fourth, 1598, received the sum of seven shillings and four-pence, for six bundles of rushes and two pair of brass snuffers.”

Our commentator’s erudition likewise manifested itself in a dramatic piece which he wrote and published, entitled No cure, no pay.

In the early part of his life, he distinguished himself by his filial affection in the support of his poor and aged parents, through the various means above detailed: will not then the feeling heart experience a pang at being informed, that, bowed down by age, poverty, infirmity, and a long and painful illness, poor Harry Rowe expired in the poor-house at York, on Thursday morning, the second of October.

October 13, 1800.

S.B.

383 words.

Similar

29 August 1570: On arriving in Yorkshire, Archbishop Grindal declares war on bloody-minded folk-Catholicism

29 August 1570: On arriving in Yorkshire, Archbishop Grindal declares war on bloody-minded folk-CatholicismSearch

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter