14 September 1864: In his last race, the legendary Blair Athol faces his great rival, General Peel, in monsoon conditions in the St Leger Stakes (Doncaster)

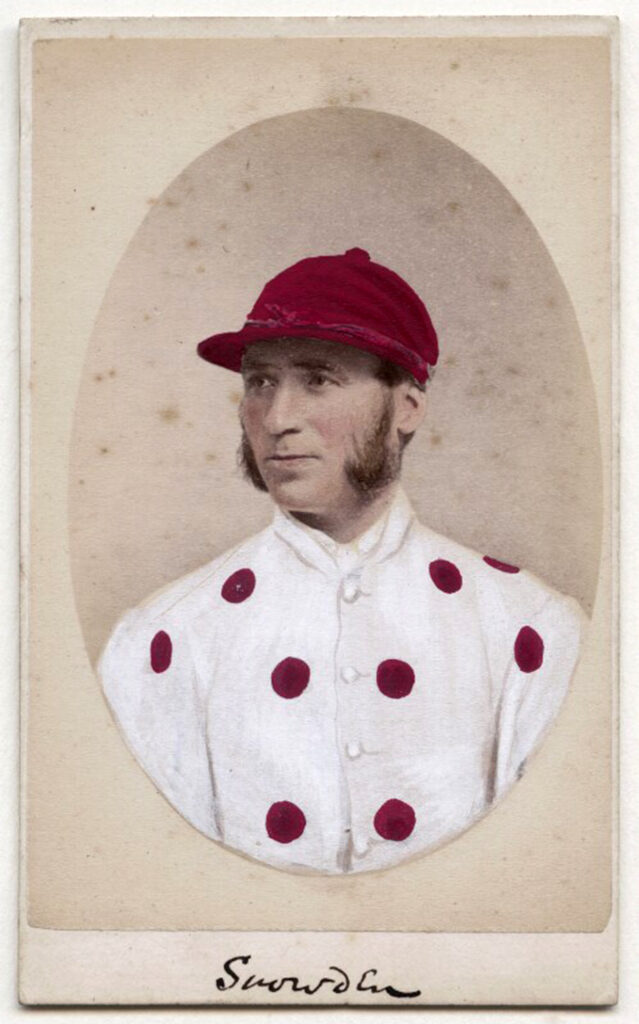

Jockey Jem Snowden (Martinucci 1877).

Our Turf Reporter. 1864/09/15. A Professional Account. Sheffield Independent. Sheffield. Get it:

.Excerpt

Rain, which had increased up to this period, began to fall heavily, and directly the horses had gone through their preliminary canters it poured in torrents, and the jockey’s colours became indistinguishable from sheer saturation. The course at this period presented a most extraordinary appearance, innumerable umbrellas completely roofing each side of the course, and the summits of the stands were similarly covered. Mr Marshall got the ten competitors to the starting post in capital time, but the rain fell in such perfect sheets that it was doubted whether any attempt would be made to effect a start. After one false start, and when people had made up their minds that the strong wind and rain would cause some delay, a sudden roar of “They are off!” caused umbrellas to be furled on the stands, and the horses were seen in a compact body rushing towards the hill, but after they had gone a few hundred yards it was impossible to tell what were the colours, although the crimson jacket of Ely was observed in front. The excitement now became intense, as it was impossible to recognise distinctly horses or colours, and nothing could be ascertained until a quarter of a mile from home, when Miner, General Peel, Ely, and Cambuscan were seen to be in front, and the white face of Blair Athol was made out at their quarters on the stand side of the course. General Peel came on apparently full of running, followed by Cambuscan, and the former looked as if about to win in a canter, when enthusiastic shouts for Lord Glasgow were heard on all sides. At the distance, however, Wells was hard on the General, and Cambuscan looked momentarily formidable, but in a stride or two farther young Snowden called upon Blair Athol, and the Derby winner answering instantly, rushed to the front, and amidst great excitement won in a canter by two lengths from General Peel, the same distance by which he landed the Derby. Immense cheering followed the result, and Snowden and Blair Athol had great difficulty in returning to the enclosure, as the crowds pressed forward to pat and caress the hero of the day. Immediately after the grand race, the spectators, many of whom had their clothes wet to the skin, began to disperse; and to add to the uncomfortable state of affairs, the water had accumulated in complete ponds, and to get from the course it was impossible to escape without stepping ankle deep in sandy slush.

Comment

Comment

The author’s comparison of Doncaster and southern races is instructive.

The Tuesday summer festivals of the South at Epsom, Ascot, and Goodwood, are regarded as pleasure meetings, and with the sport is combined all the features of picnicking and a monster fête champêtre. Dashing equipages, blue veils, and light siphonias, with an abundance of champagne and commoner beverages, are most important elements on The Hill at Epsom; and the diversions of knock-’em-downs and other holiday-making pastimes throw a strong infusion of Greenwich Fair into the proceedings. At Doncaster, however, things are widely and essentially different. The countless thousands who throng the Town Moor take a sober and almost solemn interest in the racing, and compared with Epsom and Ascot, the course, when the crowd is at its height, presents quite a sombre appearance. The late period of the season would naturally admit of no great gaiety, but apart from this, the idiosyncrasy of the Yorkshire population is diametrically opposed to that of the masses who congregate upon Epsom Downs. Nine out of every ten Londoners who witness the Derby know no more about the actual contest than the names of the two or three favourites, and except a feeble interest stimulated by an investment in a half-crown “sweep,” he cares no more what will win than the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the North of England the contrary is the case, and Yorkshiremen, who are famous for their love of horses, assemble at Doncaster from a pure love of the noble sport, and have a contempt for the frivolous amusements of Epsom. The most humble of the innumerable operatives from the neighbouring town of Sheffield who flock into Doncaster is an authority on “t’ Leger,” and can tell you the latest betting and the most recent intelligence concerning the favourites or outsiders, and will talk as familiarly of John Scott, John Osborne, or l’Anson, as any patrician owner of horses. Indeed, were any Southerner to decorate himself with dolls or feathers at the Northern festival, and attempt to imitate the wild vagaries of Epsom on the Yorkshire Town Moor, he would be regarded almost as a maniac, and we cannot say what form of indignation might not manifest itself among the populace. Traditions of horse races and turf lore generally are cherished with affection throughout the county of many acres, and the great contests form landmarks of which Yorkshiremen regulate their memories of social and political events. The Great St. Leger, however, is a race which not only interests and excites the residents of its especial locality, but throughout England the issue is awaited with anxiety among all classes who possess any concern for the welfare of the national pastime. The records of the St. Leger chronicle some of the most brilliant and remarkable encounters in the history of the turf, and the race has been famous for its unexpected results and its surprises.

Another article on the same page sets the scene:

A rainy St. Leger! Such was the cheerful anticipatory exclamation of thousands of persons when they rose yesterday morning. A pouring St. Leger! That was the melancholy and terse description of the race with which on their return visitors to Doncaster consoled those of their friends who had been prevented from going. It sounds dreary enough certainly – sufficiently dreary to please the most dyspeptic and morose stay-at-home. But it wasn’t so in reality, and the person who thinks that Yorkshiremen would be deprived of all enjoyment at their great annual festival by reason of any quantity of rain, very little understands the nature and habits which they have in common with the rest of their countrymen. The English appreciate the delights of fine days with a zest that rarity only can give; but if pouting rain should come upon them at a time when they mean to enjoy themselves, they treat it with sublime contempt, and only make their soaked garments and bedraggled appearance an additional source of fun. That we all did enjoy ourselves yesterday, in spite of rain, and dripping clothes, and spoiled bonnets, is an unmistakable —–. First there was the drive, with all its attendant pleasures notwithstanding the rain – which, in fact, was only beguiling us with a little preliminary skirmishing. Not the least pleasant part of this was the fact that we were leaving the blackness and smoke of Sheffield behind if only for one day, and to make us appreciate this mercy the more sundry and diverse small boys, stationed at points of vantage, celebrated our departure with hideous cheers, while the more daring shied sods at the ladies’ bonnets and the gentlemen’s hats. This innocent and instructive pastime they continued unmolested, except occasionally, when their shots were directed more accurately than usual, some irate gentleman would pull up, and after a vain attempt to trample them down with heavy cavalry, would indulge in an equally vain attempt to catch them by an infantry expedition. The more facetious of our enlightened youthful population attached tin kettles, old shoes, and other objects of interest and delight to their fellow labourers, to any carriages that afforded an available projection behind; while the more avaricious of the same class pursued the rolling vehicles with a polite request to “Chuck us a ha’penny.” But by the time Attercliffe Common was passed these enterprising youths were distanced, and then we were able to devote some attention to a consideration of the structure of neighbouring vehicles, to the most popular style of motive power in the shape of a horse, and to make curious and amazed calculations at to the limit that might be placed on the capacity of the smallest and wretchedest pony to convey any number of heavy women thirty-six miles. They were a queer lot certainly. Every imaginable conveyance had its representative, from boxes on wheels, compared with which an Ancient Briton’s war chariot was a work of art, to the aristocratic and well-appointed drag and four. Carts made to hold four, or which, perhaps, by a bold stroke of imagination, the builder may have conceived capable of accommodating “a small ‘un” besides, were packed with six or eight stout middle-aged females and burly men, while others calculated to hold six or so, were persuaded to take in ten or twelve, or even thirteen. In most instances the size of the pony varied in inverse proportion to the weight of the load; and the speed at which it was made to travel seemed to be based on the calculation that the more people it drew the greater was the importance of reaching the race course soon. By far the most popular vehicles were light carte of a kind which a critical observer might remember to have seen doing much more menial offices on working days. Now, however, they are furbished up, and instead of fish or flesh, or salt or apples, bear proudly the proprietor with his better half, and a few “comfortable” friends. The chief characteristic of such groups as these is that the men invariably occupy the seats of honour in front, while their wives are fain to content themselves with any ledge, called by courtesy a seat, there may happen to be behind. Very different is the solemn manner in which these family parties plod along from the dashing style of the dogcarts or gigs of roué young men, who, cigar in mouth, drive along at a rattling pace so long as they do go, but who, finding the process somewhat exhaustive, are obliged to restore their failing energies at every public house they come to. On the whole, therefore, these hares do not make better running than the tortoises. The nearer we get to Doncaster the more numerous and various do the vehicles become, and to them are now added a fair proportion of pedestrians, for the most part disreputable youths, “loafers,” intermingled with whom are lads in whom it is not difficult to recognise apprentices who will be found absent this morning without leave. Doncaster itself, of course, is like a fair. The thousands poured in by train unite with those who have come by road, and the streets ere crowded with all manner of men, women, and children, steadily drifting towards the racecourse, but not in too great a hurry to be inattentive to the various attractions which energetic tradesmen press upon them. “K’rect cards and a pencil” are thrust into your face at every turn, while walking-stick vendors and the hawkers of goods which appeal to the inner man seem to drive a roaring trade. “Parkinson’s butter scotch” establishment is besieged by a crowd second only to that which surrounds the Subscription Rooms. Towards the racecourse appear the simple establishments of the ingenious vagabonds who make it their business to conjure the money out of fools’ pockets, and thimble-rigging, spinning, the card trick, and other knavery drive a roaring trade. Aunt Sally, too, is popular, but the weather is rather against the usual success of these “national pastimes,” and the public for the most part crowd upon the course, eating and drinking, and wishing the racing would begin. That eating and drinking is regarded as one of the chief duties of the day is manifest from the very extensive provision which the carriage people now produce, and from the earnest manner in which they set about investigating the contents of hampers. Nigger singers, accordion players, et hoc genus omne, with that insight into human nature which they pick up by hard experience, seem to know the warming effect which champagne and pigeon pie have upon the heart, and ply their trade with due industry just at the right time. Then there are interchanges of courtesy between the carriages, and there is time to look round on the wonderful crowd of human beings there assembled. The stands are closely packed, and the betting ring is a scene of busy animation. The crowd which swarms over the course and clog the barriers, and gets as near the sacred enclosure as possible, is animated too, but with diverse interests. The names Blair Athol and General Peel are in every month, but all the betting that the ordinary public intends to venture is made by this time, so their discussion of the merits of the “cracks,” while immensely earnest, lacks the boisterous and noisy excitement that prevails among professional and regular betting men. They content themselves with looking out good places and waiting with more or less of patience the first race (Our Non-Racing Reporter 1864/09/15).

Something to say? Get in touch

Original

The competitors were, as usual, saddled in the rear of the Grand Stand, and a great crowd formed and ranged themselves in a lane through which the horses passed on to the course. General Peel and Blair Athol (who was last out) being received with such uproarious cheers as none but genuine tykes know how to enunciate. Rain, which had increased up to this period, began to fall heavily, and directly the horses had gone through their preliminary canters, it poured in torrents, and the jockey’s colours became undistinguishable from sheer saturation. The course at this period presented a most extraordinary appearance, innumerable umbrellas completely roofing each side of the course, and the summits of the stands were similarly covered.

Mr. Marshall got the ten competitors to the starting post in capital time, but the rain fell in such perfect sheets that it was doubted whether any attempt would be made to effect a start in such a deluge. After one false start, and when people had made up their minds that the strong wind and rain would cause some delay, a sudden roar of “They are off!” caused umbrellas to be furled on the stands, and the horses were seen in a compact body rushing towards the hill, but after they had gone a few hundred yards it was impossible to tell what were the colours, although the crimson jacket of Ely was observed in front. The excitement now became intense, as it was impossible to recognise distinctly horses or colours, and nothing could be ascertained until a quarter of a mile from home, when Miner, General Peel, Ely, and Cambuscan were seen to be in front, and the white face of Blair Athol was made out at their quarters on the Stand side of the course. General Peel came on apparently full of running, followed by Cambuscan, and the former looked as if about to win in a canter, when enthusiastic shouts for Lord Glasgow were heard on all sides. At the distance, however, Wells was hard on the General, and Cambuscan looked momentarily formidable, but in a stride or two farther young Snowden called upon Blair Athol, and the Derby winner answering instantly, rushed to the front, and amidst great excitement won in a canter by two lengths from General Peel, the same distance by which he landed the Derby; Cambuscan was a good third, and the position he secured justified the outlays which had been made upon him overnight by his party for a place. Immense cheering followed the result, and Snowden and Blair Athol had great difficulty in returning to the enclosure, as the crowds pressed forward to pat and caress the hero of the day.

Mr. Jackson, against whom innuendos had been thrown out in connection with the Derby, was most excited at the issue, and Aldcroft’s character and professional fame was completely vindicated, as there can be not the slightest particle of a doubt that General Peel, despite his grand looks, has a soft heart, and lacks the stamina to stay over a distance of ground, as he fairly died away to nothing when Wells endeavoured to get an effort out of him.

The Derby and St. Leger, it may be mentioned, have not been won by the same animal since 1853, when the two prizes of North and South were borne away by West Australian.

Immediately after the grand race, the spectators many of whom had their clothes wet to the skin, began to disperse; and to add to the uncomfortable state of affairs, the water had accumulated in complete ponds, and to get from the course it was impossible to escape without stepping ankle deep in sandy slush.

628 words.

Similar

4 July 1838: 26 girls and boys drown trying to escape via a tunnel from flash flooding in Huskar Colliery, Silkstone, Barnsley, after the steam lifts fail during a rainstorm

4 July 1838: 26 girls and boys drown trying to escape via a tunnel from flash flooding in Huskar Colliery, Silkstone, Barnsley, after the steam lifts fail during a rainstormSearch

Donate

Music & books

The Headingley Gallimaufrians: a choir of the weird and wonderful.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter