23 June 1413: Walking from York to Bridlington on a hot Midsummer’s Eve, the husband of the Christian mystic Margery Kempe suggests a resumption of sexual relations

Margery Kempe. 2014. The Book of Margery Kempe. Ed. Joel Fredell. Online: Southeastern Louisiana University. Licensed under CC, without modification. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

It befel up on a Fryday on Mydsomyr Evyn in rygth hot wedyr, as this creatur was komyng fro Yorke ward, beryng a botel wyth bere in hir hand, & hir husbond a cake in hys bosom, he askyd hys wyfe this qwestyon:

“Margery, yf her come a man with a swerd & wold smyte of myn hed, les than I schulde comown kindly wt yow as I haue do befor, seyth me trewth of yowr consciens, for ye sey ye wyl not lye, whethyr wold ye suffyr myn hed to be smet of, er ellys, suffyr me to medele with yow a yen as I dede sum tyme?”

“Alas, ser,” sche seyd, “why meue ye this mater, & haue we ben chast this viii wekys?”

“Ffor I wyl wete the trewth of yowr hert.”

And than sche seyd wt gret sorwe, “Forsothe I had leuar se yow be slayn than we schuld turne a yen to owyr vnclennesse.”

And he seyd a yen, “Ye arn no good wife.”

& than sche askyd hir husbond what was the cawse, tht he had not medelyd wt hir viii wekys be for, sythen sche lay wt hym euery nygth, in hys bedde. And he seyd he was so made a ferde whan he wold a towchyd hir, tht he durst no mor don.

“Now good ser amend yow & aske god mercy, for I teld yow ner iii yer sythen tht ye schuld be slayn sodeynly, & now is this the thryd yer, & yet I hope I schal han my desyr. Good sere, I pray yow grawnt me tht I schal askyn, & I schal pray for yow tht ye schul be sauyd thorw the mercy of owyr lord Ihusu Cryst. And ye schul haue mor mede in heuyn than yyf ye weryd vowan hayr or an haburgon. I pray yow, suffer me to make a vow of chastyte in what bysshopys hand tht god wele.”

“Nay,” he seyd, “that wyl I not grawnt yow, for now may I vsyn yow wyth owtyn dedly synne, & than mygth I not so.”

Than sche seyd a yen, “Yyf it be the wyl of the Holy Gost to fulfyllyn that I haue seyd, I pray god ye mote consent ther to. And yf it be not the wyl of the Holy Gost, I pray God ye neuyr consent ther to.”

Than went thei forth to Brydlyngton ward in rygth hoot wedyr, the forn seyd creatur hauyng gret sorwe & gret dred for hyr chastite. And as thei cam be a cros, hyr husbond sett hym down vndyr the cros, clepyng hys wyfe vn to hym, & seyng this wordys on to hir:

“Margery, grawnt me my desyr & I schal grawnt yow yowr desyr. My fyrst desyr is tht we xal lyn stylle to gedyr in o bed, as we han do be for; the secunde, tht ye schal pay my dettys er ye go to Ierualem; & the thrydde, tht ye schal etyn & drynkyn wt me on the fryday as ye wer wont to don.”

“Nay, ser,” sche seyd, “to breke the Fryday I wyl neuer grawnt yow whyl I leue.”

“Wel,” he seyd, “than schal I medyl yow a geyn.”

Sche prayd hym tht he wold yeue hir leue to make hyr praerys, & he grawntyd it goodlych. Than sche knelyd down be syden a cros in the feld, and preyd in this maner wyth gret habundawns of teerys:

“Lord God, thu knowyst al thyng; thow knowyst what sorwe I haue had to be chast in my body, to the al this iii yer, & now mygth I han my wylle, & I dar not, for lofe of the. Ffor yyf I wold brekyn tht maner of fastyng whech thow comawndyst me to kepyn on the Fryday wt owtyn mete or drynk, I xuld now han my desyr. But blyssyd Lord, thow knowyst I wyl not contraryen thi wyl. And mekyl now is my sorwe les than I fynde comfort in the. Now, blyssed Ihusu, make thi wyl knowyn to me vn worthy, tht I may folwyn ther aftyr & fulfyllyn it wt al my myghtys.”

And than owyr lord Ihusu Cryst wyth gret swetnesse spak to this creatur, comawndyng hir to gon a yen to hir husbond, & prayn hym to grawntyn hir tht sche desyred:

“& he xal han tht he desyreth. Ffor, my derworthy dowtyr, this was the cawse tht I bad the fastyn, for thu schuldyst the sonar opteyn & getyn thi desyr, & now it is grawntyd the. I wyl no lengar thow fast, ther for I byd the in the name of Ihusu ete & drynk as thyn husbond doth.”

Than this creatur thankyd owyr Lord Ihusu Cryst of hys grace & hys goodness, sythen ros up & went to hir husbond, seyng vn to hym:

“Sere, yf it lyke yow ye schal grawnt me my desyr & ye schal haue yowr desyr. Grawntyth me tht ye schal not komyn in my bed, & I grawnt yow to qwyte yowr dettys er I go to Ierusalem & makyth my body fre to God, so tht ye neuer make no chalengyng in me to askyn no dett of matrimony aftyr this day whyl ye leuyn, & I schal etyn & drynkyn on the Fryday at yowr byddyng.”

Than seyd hir husbond a gen to hir, “As fre mot yowr body ben to god as it hath ben to me.”

Thys creatur thankyd god gretly, enioyng tht sche had hir desyr, prayng hir husbond tht thei schuld sey iii pater nrs in the worshep of the Trinyte, for the gret grace tht he had grawntyd hem. & so they ded, knelyng vnder a cros, & sythen thei etyn & dronkyn to gedyr in gret gladnes of spyryt. This was on a Fryday on Mydsom᷑ euyn.

Than went thei forth to-Brydlyngton-ward, and also to many other contres, & spokyn wyth Goddys suawntys, bothen Ankrys & reclusys, & many other of owyr Lord’s louerys, wt many worthy clerkys, doctorys of dyuynyte, & bachelers also, in many dyuers placys. & this creatur to dyuers non dyscrescion of hem schewyd hir felyngs & hyr contemplacyons as sche was comawndyd for to don, to wetyn yf any disseyt were in hir felyngys.

Comment

Comment

Barry Windeatt makes a convincing case for the date (Kempe 2004).

Following divine intervention, Mr. accepts that it is all over.

I don’t think Shakespeare knew Kempe, but Twelfth Night: “Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?”

Sarah J Biggs of the British Library’s medieval team:

The story goes that when Colonel W Butler Bowdon was looking for a ping-pong bat in a cupboard at his family home near Chesterfield in the early 1930s he came across a pile of old books. Frustrated at the disorder, he threatened to put the whole lot on the bonfire the next day so that bats and balls would be easier to find in future. Luckily a friend advised him to have the books checked by an expert and shortly afterwards Hope Emily Allen identified one as the Book of Margery Kempe (Flood 2014/03/20).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

Comment

Comment

The fiscal fatigue caused by the Hundred Years’ War was a cause of the 1343-45 Truce of Malestroit.

Thomas Sheppard is a good starting point for respectively Ravenser and Ravenser Odd:

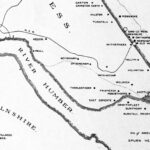

William Shelford … points out that Spurn Point, even in Roman times, must have been 2,250 yards at least beyond the present coastline ; and that at or near this spot the Danes landed in 867, planted their standard “The Raven,” and practically originated the town of Ravensburg, or Ravenser, or Ravenseret, within Spurn Head. The town developed into “one of the most wealthy and flourishing ports of the kingdom. It returned two Members to Parliament, assisted in equipping the navy, had an annual fair of thirty days, two markets a week, is mentioned twice by Shakespeare,[King Henry VI, part iii, Act iv, Scene 7; and Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1] and considered itself honoured by the embarkation of Baliol with his army for the invasion of Scotland in 1332; by the landing of Bolingbroke, afterwards Henry IV, in 1399; and by the landing of Edward IV in 1471, not long after which it was entirely swept away.” Today, we cannot even be certain where the place was. […] In 1296 “Kaiage” [right to tax wharf occupation] was granted to the inhabitants by Edward I. Two years later Ravenser petitioned the king for certain privileges, and offered 300 marks in payment. In 1300 the magistrates of Ravensere were enjoined to stop the export of bullion; in 1305 it sent Members to Parliament. In 1310 Ravensere remonstrated against the depredations of the Earl of Holland, and in the same year Ravenness sent ships for Edward II.’s expedition to Scotland. Two years later the inhabitants were empowered to levy a tax to defend their walls. In 1323 commissions were issued for the “Wapentak of Ravensere.” In 1335-6 warships of Ravensere are referred to, and in 1341 Ravensere sent one Member to “a sort of” naval Parliament of Edward III. In 1346 one ship only was sent by Ravenser to the siege of Calais; (Hull sent 16). In 1355 bodies were washed out of their graves in the chapelyard at Ravenser. In 1361 [i.e. 1362 – the Second St. Marcellus flood] the floods drove the merchants to Hull and Grimsby; and by 1390 nearly all trace of the town, as such, was gone.* In 1413 a grant was made for the erection of a hermitage at Ravenscrosbourne, and in 1428 Richard Reedbarowe, the hermit of the chapel of Ravensersporne obtained a grant to take tolls of ships for the completion of his light-tower. In 1538 Leland refers to Ravenspur in his ” Itinerary,” which seems to be the last reference to the place. As pointed out elsewhere, the place is not included in Holinshed’s ” List of Ports and Creeks,” which was issued before 1580.

[…]

Ravenser-odd (also referred to as Odd near Ravenser, Ravenserot, Ravensrood, Ravensrodd, Ravensrode, etc.), probably originated in the early part of the thirteenth century, soon after Ravenser, the adjoining port, came to be of importance. Ravenser-odd was apparently built on an island.

In 1251 some monks obtained half an acre of ground on which to erect buildings for the preservation of fish, in the burg of Od near Ravenser. The chronicler of Meaux wrote that “Od was in the parish of Esington, about a mile distant from the mainland. The access to it was from Ravenser by a sandy road covered with round yellow stones, scarcely elevated above the sea. By the flowing of the ocean it was little affected on the east, and on the west it resisted in a wonderful manner the flux of the Humber.”

In 1273 there was a dispute about a chapel at Od, and this was carried on for some time.

In 1300 Edward I. gave some lands in Ravenserodde to the convent of Thornton in Lincolnshire, and others to St. Leonard’s Hospital, York.

In 1315 the burgesses of Ravenserod agreed to pay the king £50 for the confirmation of their charters, and “Kaiage” for seven years. In 1326 the king granted dues and customs in the port of Ravenserod, and about 1336 William De-la-Pole left Ravenserod for Hull. Ravenserode sent a representative to Edward III.’s “naval Parliament” in 1344, as well as a man well versed in naval affairs.

In 1346 Ravensrodde was one of the places mentioned by the Abbot of Meaux as suffering by the sea. In the following year it was frequently inundated, and in 1360 [presumably 1362] “Ravenser Odd was totally annihilated by the floods of the Humber and inundations of the great sea.”

In 1355 the bodies in the chapel yard, which, “by reason of inundations were then washed up and uncovered,” were removed and buried in the churchyard at Easington.

About this time we read the following curious note in the Meaux Chronicle : — ” When the inundations of the sea and of the Humber had destroyed to the foundations the chapel of Ravenserre Odd, built in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so that the corpses and bones of the dead there buried horribly appeared, and the same inundations daily threatened the destruction of the said town, sacrilegious persons carried off and alienated certain ornaments of the said chapel, without our due consent, and disposed of them for their own pleasure ; except a few ornaments, images, books, and a bell which we sold to the mother church of Esyngton, and two smaller bells to the church of Aldeburghe. But that town of Ravenserre Odd, in the parish of the said church of Esyngton, was an exceedingly famous borough, devoted to merchandise, as well as many fisheries, most abundantly furnished with ships and burgesses amongst the boroughs of that sea-coast. But yet, with all inferior places, and chiefly by wrong-doing on the sea, by its wicked works and piracies, it provoketh the wrath of God against itself beyond measure. Wherefore, within the few following years, the said town, by those inundations of the sea and of the Humber, was destroyed to the foundations, so that nothing of value was left.”

Notwithstanding this, “In the Hedon inquisition of January 1401, the chapel of Ravenserodde, with the town itself, was declared to be worth, in spiritualities, more than £30 per annum.”

William Wheater treads a similar path, perhaps better – haven’t read it (Wheater 1889).

The rise and fall of a tsunami are among the 15 signs of doom in a Middle English poem, The Pricke of Conscience, and are illustrated in a medieval (ca. 1410) window in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York:

Þe first day of þas fiften days,

Þe se sal ryse, als þe bukes says,

Abowen þe heght of ilka mountayne,

Fully fourty cubyttes certayne,

And in his stede even upstande,

Als an heghe hille dus on þe lande.

Þe secunde day, þe se sal be swa law

Þat unnethes men sal it knaw.

Þe thred day, þe se sal seme playn

And stand even in his cours agay[n],

Als it stode first at þe bygynnyng,

With-outen mare rysyng or fallyng

(Anon 1863)

Britta Sweers, “Trutz, Blanke Hans” – Musical and Sound Recollections of North Sea Storm Tides in Northern Germany

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter