15 December 1888: Leeds’s most popular wassailing song, according to Frank Kidson

Frank Kidson. 1888/12/15. Christmas Melodies. Leeds Mercury. Leeds. Get it:

.Indices for all ballads etc. mentioned here: Roud 278 @ Vaughan Williams ML & Bodleian

Excerpt

GOD REST YOU MERRY GENTLEMEN

We are not daily beggars

That beg front door to door,

But we are neighbours’ children,

Whom you have seen before.

For it is the Christmas time,

And we travel far and near;

So God bless you and send you

A happy new year.

God bless the master of this house,

The mistress also,

And all the little children

That round the table go.

For it is the Christmas time, &c.

Call up the butler of this house,

Put on his golden ring;

Let him bring us a glass of beer,

And better we shall sing.

For it is, &c.

We’ve got a little purse

Made of stretching leather skin;

We want a little of your money

To line it well within.

For it is, &c.

Comment

Comment

Who knows more about another song collected by Kidson, “The First Good Joy That Mary Had”? Why does he call it “a barbarous production” and omit the lyrics?

Via Malcolm Douglas’s comment at Mudcat.

Something to say? Get in touch

Original

O, you merry, merry souls,

Christmas is a-coming;

We shall have flowing bowls, Dancing, piping, drumming.

– Round About Our Coal Fire (1740).

Was Christmas really merrier when we were boys than it is now? It is a difficult matter to settle, for at that time we had the solace of Christmas-boxes and unlimited spicecake, and not the disadvantages of digestions which will not be played with, and bills which must be paid. Of course, all these things have great influence, but still for all that, looking at the question with an unprejudiced eye, I think it was, on the whole, a more cheerful festival than it is now. Christmas now-a-days starts before the leaves are off the trees, for in this race to the front Christmas cards are shown and other preparations made so early that by the time the season really does come on we are sick of the whole thing.

Fifty or sixty years ago, however, a Yorkshire Christmas was to a stranger a thing to be remembered, more especially in the little clothing villages and towns roundabout Leeds. The people were really in earnest, and the day was kept with full honours. At such villages there was an open-hearted hospitality scarcely to be now realised. Everybody was welcome, and literally open-house was kept. It is said to have been no uncommon thing for one neighbour to run to another with such a request as this – “Eh! Mrs. so and so, I wish you’d lend us your beef, we’ve eaten all ours, and my brother from _______ has just come in, and there’s nothing in the house to set in front of him.” The prospect of a strange and hungry man’s attack on the sirloin would be rather disconcerting to a modern housekeeper. The answer to a demand like this would be rather more polite than hospitable; and not “Aye, doy, ye sall hev it, wi’ pleasure.”

Among the villagers, the most important at this season would be the half-dozen or so who formed the village band, and who in general were skilled performers and enthusiastic lovers of the musical art. Their performances of Handel and Bach were not to be sneered at, though the performers had nothing better on than the blue “brat,” and spoke a dialect as rough and uncouth as themselves. The band was generally a string one, and their place of meeting either in some weaving shop or the school-room. The man who played the “bass” would be no unimportant character; he would, perhaps, be some gigantic specimen of humanity, or as frequently a little, twisted, “key-legged” fellow, who like enough was the tailor, and would be sure to be called “Tommy,” and to be the recipient of much harmless chaff.

Rosin was, of course, in great request, and produced not in dainty little card boxes, but in huge lumps from the village tinner’s shop. “Nah, lads,” one would say, “give ‘us hod o’t rosin, and let’s hev ‘Wild Shepherds.'” To such a little body Christmas would mean weeks of rehearsing, for possibly an oratorio would be produced, and all the favourite Christmas carols would be performed before the principal houses in the district on Christmas and New Year’s Eve. On Christmas Day some of them would be required in the church, for it was before the now popular harmonium was installed.

In those old days people were content with the Christmas carols of the past – those which have stood the test of many generations of singers, and much was gained from association and from endeared memories. There is now a custom, much to be reprehended, of giving new lamps for old, of setting aside our old and standard favourites in favour of new productions which greatly lack the force aid simplicity as well as the fitness derived from familiarity. Intricacy of measure and harmony seem alone to be aimed at, rather than the well-marked rhythm and melody found in the old ones. It appears as if any church or chapel organist feels no compunction in ousting out our old friends, and where their genius does not extend to the production of new words, a still greater crime is committed by wedding their lucubrations to the old ones. The familiar “While shepherds watched their flocks by night” has been selected more than once as a special victim. “Christians Awake,” so far as the writer is aware, has not yet suffered profanation, and long may old Dr. Wainwright’s heaven-inspired strains be protected. It may, perhaps, be memory that lends a little charm; but he must be stolid indeed who can hear the solemn words carolled forth in the clear frosty morning air without some thrill of emotion.

Christmas songs are, of course, of two distinct classes; one dealing with the purely religious aspect of the season, and the other with the festive. These latter may be more definitely classed as the Wassail songs, the word “carol” including both these classes. The derivation of the word “wassail ” has been times out of mind set forth, but the following possage from Stratt’s “Sports and Pastimes” fixes the period of the original saying from whence the word is said to owe its derivation:- “The Wassail is said to have originated from the words of Rowena, the daughter of Hengist, who, presenting a bowl of wine to Vortigern, the King of the Britons, said, ‘Wæs hæl,’ or, ‘Health to you.'” Wassail bowls filled with liquor seem first to have been carried about by girls, who, presenting the bowl to their superiors, received a present of money for this act of homage or courtesy. As such a proceeding was soon seen to be a profitable one, their office was quickly usurped by men. From the presentation of the Wassail cup the origin of Christmas-boxes may, perhaps, be dated. In all parts of the country the offering of the Wassail cup was used as a means for collecting gifts, and it is stated that the custom still holds in Gloucestershire, but with this great difference, the bowl is empty and ready for receiving donations of either liquor or money. The following verse commences the Gloucestershire Wassail song, and is well known. The tune was given with the rest of the words in these columns some time ago:-

Wassail! wassail! all over the town,

Our toast it is white and our ale it is brown;

Our bowl it is of the good maplin [maple] tree,

So here’s, good fellow, I’ll drink to thee.

The wassail-cup for indoor use among the better class of people was of silver; but that carried about by the peasants was always of wood (as above), and was gaily decorated with a crown of bent boughs, gay ribbons, and streamers. One of our popular Yorkshire carols alludes to this custom, and here, it seems, that green holly was the decoration:-

Here we-come a wassailing, among the leaves so green,

Here we come a-wassailing, so fair to be seen;

Our wassail-cup is made of the rosemary-tree,

And your beer is made of the best barley.

It is curious to observe that the wassail-bearers’ songs express in different words exactly the same sentiments. The following is but little known; it will be found in Ritson’s “Antient Songs,” 1790, introduced with the words-

“A carol for a wassail-bowl, to be sung upon Twelfth Day at Night, to the tune of ‘Gallants, come away.’ From a collection intitled, ‘New Christmas Carols;’ no date, black letter, in the curious study of that ever-to-be respected antiquary, Anthony-à-Wood, in the Ashmoleian Museum:-

A jolly wassel bowl,

A wassel of good ale,

Well fare the butler’s soul,

That setteth this to sale.

Our jolly wassel.

Good dame here at your door,

Our wassel we begin;

We are all maidens fair,

We pray you let us in.

With our wassel.

Our wassel we do fill

With apples and with spice;

Then grant us all good-will,

To taste here once or twice

Of our good wassel.

If any maidens be

Here dwelling in this house,

They kindly will agree,

To take a full carouse

Of our wassel.

But here they let us stand,

See, freezing in the cold;

Good master give command

To enter and be bold

With our wassel.

Much joy into this hall,

With us is entered in,

Our master first of all,

We hope will now begin

With our wassel.

And after his good wife,

Our spiced bowl will try;

The Lord prolong your life,

Good fortune we espy

For our wassel. &c. &c. &c.

Compare the fourth verse of this with the Gloucestershire version:-

Be here any maid? I suppose there be some,

Don’t let the poor men stand on the cold stone,

But step to the door and draw back the pin,

And the fairest maid in the house let us all in.

The most popular wassail song in Leeds is the following:-

“GOD REST YOU MERRY GENTLEMEN.”

We are not daily beggars

That beg front door to door,

But we are neighbours’ children,

Whom you have seen before.

For it is the Christmas time,

And we travel far and near;

So God bless you and send you

A happy new year.

God bless the master of this house,

The mistress also,

And all the little children

That round the table go.

For it is the Christmas time, &c.

Call up the butler of this house,

Put on his golden ring;

Let him bring us a glass of beer,

And better we shall sing.

For it is, &c.

We’ve got a little purse

Made of stretching leather skin;

We want a little of your money

To line it well within.

For it is, &c.

The tune as sung in Leeds and as here printed is different, especially in the second part, from the copy in Chappell’s “Popular Music,” as are also the words. There are many more verses, which are not necessary to be here set down. The stretching capabilities of the purse are always strongly emphasised.

Another carol, popular in Leeds some time ago, but now out of favour, was

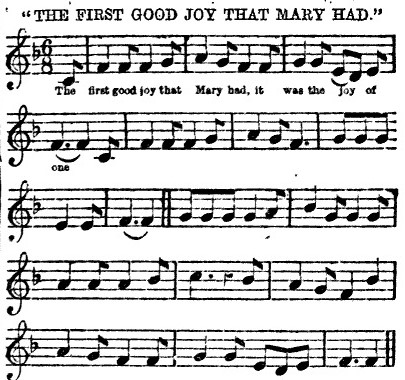

“THE FIRST GOOD JOY THAT MARY HAD.”

The tune has probably not appeared in print before, but the words are well known. The hymn is a barbarous production, and the “joys that Mary had” extend up to seven.

[Several carols from elsewhere, the boar’s head, general description of waits]

The special form of asking for Christmas-boxes generally runs in rhyme, and varied in different parts of the country. That in Leeds, which is bellowed in a quick, hoarse voice through the keyhole, is-

I wish you a merry Kersmas,

A happy New Year,

A pocket full of money,

A barrel full o’ beer,

A big fat pig to serve you all t’year,

Please will you give us my Kersmas-box.

Lately, however, a more refined request has been made in the following terms:-

A little bit of spice cake,

A little bit of cheese,

A glass of cold water,

And a penny if you please!

Many other Christmas rhymes could be found with a little looking for; in fact, an exhaustive book of Christmaa folk lore is yet to be gathered together from the fragments that remain in remote districts, and from material scattered over many volumes.

In concluding this rambling sketch of Christmas and Christmas carols, attention may be drawn to the fast-disappearing Christmas observances. It is to be feared that when the present generation is passed away little will be left of the old usages. It could not be expected that these would stand as society is now constituted, but one cannot but look with a lingering regret over these kindly customs so soon to pass away.

2244 words.

Similar

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter