19 March 1866: Corn-merchant J.R. Mortimer of Driffield opens a prehistoric burial mound on the Wolds and suggests a link to ancient Greek descriptions of Balearic rites

John Robert Mortimer. 1905. Forty Years’ Researches in British and Saxon Burial Mounds of East Yorkshire, Including Romano-British Discoveries, and a Description of the Ancient Entrenchments on a Section of the Yorkshire Wolds. London: A. Robert and Sons. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

BARROW No. 50.

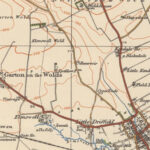

This barrow is near the western margin of some double entrenchments situated west of Aldro, and just opposite to barrow No. 113, which touches the east side of the same entrenchments. On March 19th, 1866, it measured 70 feet across, but was so far reduced as to give an elevation of 9 to 10 inches only. We turned over most of this barrow, but only found 5 handstruck pieces, and a circular disc of dark flint, several splinters of human and animal bone, and three small portions of a food-vase. In the rock below the centre was an oblong grave, 2 feet 9 inches deep, and measuring 6½ feet east and west, and 4 feet in the opposite direction. In the north corner, at the west end of the grave, was a pile of unburnt human bones, accompanied by the tooth of an ox. At the east end was a similar heap, consisting of the bones of two or more persons, on the top of which was a splinter of dark flint and a keen-edged and peculiarly-formed flint knife (fig. 172) of the same colour and measuring 1⅝ inches long and 1¼ inches broad. It is worthy of note that from this deposit two burnt splinters from a human leg-bone were taken. The bones of each of these deposits must have been freed, in a great measure, from the flesh, thoroughly disjointed, and some of them broken to pieces, previous to interment, otherwise they could not have been heaped together in the close manner in which they were found. Some of the bones of the legs and arms were entire, but all the lower-jaws had been broken, in two or more pieces, and the skulls into numerous fragments, and were mixed up in the heaps. Similarly puzzling deposits were also found in the neighbouring barrows Nos. 52, 53, and 54,[Footnote: Of such a strange mode of burial we have historical proof, for Diodorus Siculus, writing of the Carthaginians, says, “They have a strange custom about burying the dead. They cut the body up in pieces and put all the parts in an urn, and rear a great heap of stones over it.”] and they seem to have been peculiar to the barrows of this neighbourhood. The only other deposits of the kind which have come under our observation were in barrows Nos. 99, C.63, and 72.

The bottom of the grave contained unctuous earth, which 8 to 10 inches above, was replaced by rubbly chalk, which in turn was followed by another stratum of unctuous earth, reaching to the top and joining the base of the barrow. Scattered throughout the grave were numerous splinters of human bone (portions of skulls, and fragments of leg and arm bones), and bits of burnt wood, a few pieces of animal bone, two small portions of a food-vase, and one small piece of black flint.

Comment

Comment

An intriguing notional connection – has someone commented on it? The (posterior) Roman road, presumably on a previous track, just to the west creates even more fun. Historic England on part of the barrow complex.

Mortimer makes a curious error: Diodorus’s ethnology is of the Balearics, not the Carthaginians. I doubt Mortimer or his vicar father-in-law knew Ancient Greek, so the edition he accessed was probably similar to George Booth’s – previous para included because it recalls a certain Barcelona wedding:

They have a filthy custom likewise among them concerning their marriages; for in their marriage feasts, all their friends and household servants, as they are in seniority of age, one after another, carnally know the bride, till at length it come to the bridegroom’s turn, who has the honour to be last. They have another strange custom likewise about the burying of their dead; they cut the carcass in pieces with wooden knives or axes, and so put up all the parts into an urn, and then raise up a great heap of stones over it (Diodorus Siculus 1700).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

22 November 1641: Snow falls at Elmswell (Driffield), and sheep farmers jostle for low ground and feed

22 November 1641: Snow falls at Elmswell (Driffield), and sheep farmers jostle for low ground and feed

Comment

Comment

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter