Ye Racehorse Inne is an 1880s Tudorbethan pub just below the racecourse at Whitehawk Camp, and on one of the routes into Brighton as you walk over from Lewes. If you can ignore the the windows and front door, its exterior hasn’t changed a great deal, although our view is somewhat obscured nowadays by the paraphernalia designed to preserve us from cars:

In 2012 Quedula of the #Brighton Bits blog documented its conversion into flats. Ah yes, said Anonymous in 2016, but

At the bottom of the big chimney is a plaque & an engraving of “Baronet”. Who was Baronet?

Despite the building’s style, Ye Olde Racehorse Baronet was a renowned Georgian mount, and the relief appears to iconify Stubbs’ well-known 1791 portrait (in the Royal Collection) of him in a flying gallop under Samuel Chifney the Elder at Newmarket (“Baronet at Speed with Chifney up”:

According to The Huntington, Baronet was bought by George, Prince of Wales, as a four-year-old in 1789 and took his name from his previous owner, Sir Walter Vavasour, Bart. He

ran undefeated in 1791, triumphing in the Oatland Stakes at Ascot Heath (June 28, 1791), and in a series of four-mile heats: His Majesty’s Plate at Winchester (July 19, 1791) and Lewes (August 4, 1791), and the King’s Plate at Canterbury (August 24, 1791) and Newmarket (October 5, 1791). After selling in 1795 to William Constable of New York, Baronet sired a number of important American racehorses.

Whereafter his fate may have been like that of Dibdin’s High-Mettled Racer:

Till at last, having labour’d drudg’d early and late,

Bow’d down by degrees, he bends on to his fate.

Blind, old, lame, & feeble, he tugs round a mill,

Or draws sand, till the sand of his hour-glass stands still;

And now, cold and lifeless, expos’d to the view,

In the very same cart, which he yesterday drew,

While a pitying crowd his sad relics surrounds –

The high-mettled racer – is sold for the hounds.

George, Prince of Wales, dominated British racing in 1790 and 1791 with lead jockey Sam Chifney. The first of the 1791 races, in which Baronet was paired with Chifney, made Baronet a celebrity and led to the Stubbs oil. Baily’s Magazine 120 years later, in 1911:

The year 1791 stands out as a red-letter date in the history of early Ascot, for at this meeting was run what was then declared to be “the greatest race ever decided in the kingdom” – namely the Oatlands Stakes. There were 40,000 people present on the day of this race. The actual stakes were 2,950 gns., for which nineteen horses started, including Baronet, belonging to the Prince of Wales. Baronet started at 20 to 1 against; and won the race. The first few horses “might have been covered with a blanket,” says the old record.

The greatest enthusiasm prevailed, and the Prince of Wales was the recipient of many congratulations, not the least of them being that bestowed by his father, who riding up to him after the race, said “Your ‘Baronets’ are more productive than mine. I made fourteen last week, but I got nothing by them; your single ‘Baronet’ is worth all mine put together!” which was royally true, for the Prince reaped the rich harvest of £7,000 out of the race.

Whether or not Baronet went to the dogs at the end, he was certainly more fortunate than Sam Chifney. Chifney was the first celebrity jockey, the finest trainer and rider of his age, and a dandy, and was widely hated. Later in that same year, 1791, it was alleged that he had deliberately lost one race on another of George’s horses, Escape, in order to lengthen the odds for another race several days later and scam the bookies.1Mortimer, Onslow, & Willett’s Biographical Encyclopaedia of British Racing (1978) and other standard works incorrectly give the year of the Escape scandal as 1790 rather than 1791, and this is reflected in Wikipedia. The Jockey Club excluded him from racing, and George in apparent solidarity withdrew from Newmarket and from own-name participation in the business, granting him a pension.

All of this, and much more can be found in The post and the paddock; with recollections of George IV, Sam Chifney and other turf celebrities (1862) by the barrister, sporting writer and novelist Henry Hall “The Druid” Dixon. Charles J. “Nimrod” Apperley’s The chace, the turf, and the road (1837) is also good, refuting the charges against Chifney, and pointing out that there were far more grounds for suspicion of cheating on the part of Charles Bunbury, who as Steward of the Jockey Club was his and George’s nemesis. And do read Robert Huish’s Memoirs of George IV (1830).

1791 was a sensational year, and The Quarterly Review reported in 1832 that when the Melton Old Club was established in around 1791-2, Charles Sackville-Germain hung a print of Baronet and Chifney – presumably taken from Stubbs – on the wall. 38 years later,

although since it was first affixed the room has undergone more than one papering and repairing, yet the same print in the same frame and on the same mail still hangs in the same place.

Chifney’s individual legacy was huge, even without the Baronet effect. Stubbs’ painting shows his innovative light-handed, slack-reined technique, which he used insofar as the horse would behave, and which was extremely successful in conjunction with two other novelties: the “Chifney rush,” letting the other riders do the work and coming up at the last moment; and modified bridle and bit designs – his Chifney bit was finally patented, and is still used today to lead horses prone to rearing. Here’s a lovely passage from his autobiographical pamphlet, modestly entitled Genius genuine (1805):

The Duke of Bedford was near taking me off his horses, saying, the people teased him because I rode his horses with a loose rein, and desired me to hold my horse fast in his running; I was sorry his grace was thus troubled, as it puts a horse’s frame all wrong; and his speed slackened where the horse has that sort of management to his mouth. My reins appeared loose, but my horse had only proper liberty, and mostly running in the best of attitudes. It’s usual, when that grooms are talking and giving orders to their riders, to hold the horse fast in his running; and where a horse is intended to make play, their orders mostly are, to hold the horse fast by the head, and let him come, or come along with him; but it’s very much against a horse to hold him fast, or let him bear on his rein in his running; it makes him run with his mouth more open, and pulls his head more in or up. This causes him, at times, to run in a fretting, jumping attitude, with his fore legs more open; sometimes it causes him to run stag-necked; this makes the horse point his forelegs, (otherwise called straight legged.) Sometimes it makes the horse run with his head and neck more down, crowding and reaching against his rider. This reaching his neck against his rider, pulls the horse’s forelegs out farther than the pace occasions. In all those attitudes his sinews are more worked and extended, he’s more exertion, his wind more locked, and thus reaching and pointing his fore-legs, makes them dwell and tire.

That the first fine part in riding a race is to command your horse to run light in his mouth; it’s done with manner; it keeps him the better together, his legs are the more under him, his sinews less extended, less exertion, his wind less locked; the horse running thus to order, feeling light for his rider’s wants; his parts are more at ease and ready, and can run considerably faster when called upon, to what he can when that he has been running in the fretting, spawling attitudes, with part of his rider’s weight in his mouth.

And as the horse comes to his last extremity, finishing his race, he is the better forced and kept straight with manner,2Editorial note: The word “manner” is knowing, putting, keeping self and horse in the best of attitudes. This gives readiness, force, and quickness. and fine touching to his mouth. In this situation the horse’s mouth should be eased of the weight of his rein, if not, it stops him little or much. If a horse is a slug, he should be forced with a manner up to this order of running, and particularly so if he has to make play, or he will run the slower, and jade the sooner for the want of it.

The phrase at Newmarket is, that you should pull your horse to ease him in his running. When horses are in their great distress in running they cannot bear that visible manner of pul ling as looked for by many of the sportsmen; he should be enticed to ease himself an inch a time as his situation will allow.

This should be done as if you had a silken rein as fine as a hair, and that you was afraid of breaking it.

This is the true way a horse should be held fast in his running.

N.B. If the Jockey Club will be pleased to give me two hundred guineas, I will make them a bridle as I believe never was, and I believe can never be excelled for their light weights to hold their horses from running away, and to run to order in, as above mentioned, as near as I thus can teach ; and it is much best for all horses to run in such ; and ladies in particular should have such to ride and drive in, as they not only excel in holding horses from running away, but make horses step safer, ride pleasanter, and carriage handsomer.3But before anyone runs away with the idea that lightness is all, read this piece by John O’Leary.

I think Baronet is shown riderless as a result of the war between Chifney and George on the one hand and the Jockey Club on the other: Chifney has been blown out of his saddle. Alternative explanations don’t wash. For example, the terracotta panel on Ye Racehorse was clearly made as it is today, so he hasn’t been eaten by the bloody seagulls. Another example. His boots face forward, so this is not a reference to the American military tradition of riderless horses at funerals:

A third, crazy example, for my own amusement, and just be grateful I haven’t got onto headless horsemen or hounds. This is obviously unrelated to the Roman Corsa dei Barberi, Race of the Barbs/Barbary Horses, an event similar to the Iberian correbous, a crucial part of the Roman Carnival from at least Dante’s time to the advent of Health & Safety in the 19th century, and shown here in Théodore Géricault’s “Riderless Racers at Rome” (1817):

Why Ye Olde Racehorse as the name for a pub on Elm Grove? I guess because Baronet is the Venn overlap between two selling points for the establishment: the racecourse and the Hanoverian halcyon. Chifney obviously frequented Brighton (sometimes in the company of George), and Baronet may well have run there, but I don’t think that’s important. The 1851 map by R. Montgomery Martin, published by John Tallis, shows no prior establishment that might have been called The Racehorse:

This is nominally a music blog, but I can’t find any songs about Baronet or Chifney and their rise and fall with which to end,4Which reminds me: neither can I find Trowbridge band Mechanical Horsetrough’s 1977 album Kaar-aaaap! It’s Mechanical Horsetrough!, which includes “The Ballad Of Red Rum.” Singer Alan Briars rings a bell via the Village Pump Folk Club. When he died,Mrs Briars, 48, said: “Things were going a bit wrong and he was lying down with his eyes closed. I thought he was close. We had the radio on with the Bristol City match on and they scored in the last minute. Suddenly, he jumped up and cheered and punched the air with his fist. He was Alan until the end.”

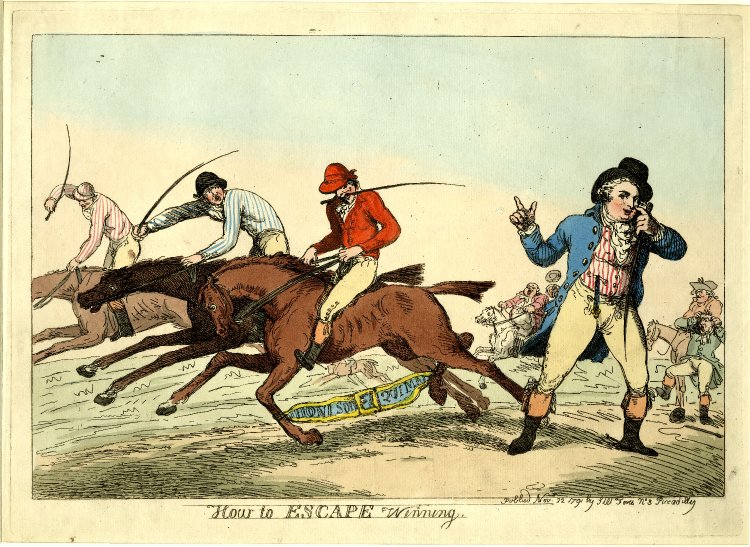

so here from the BM is Rowlandson’s caricature of George conspiring with the natty Chifney to lose, Escape’s legs bound by an Order of the Garter ribbon with the royal motto, “Honi soit qui mal y pense,” “Shame on he who thinks badly of it”:

Perhaps, perhaps

- George, perennially short of cash, put Chifney up to the supposed betting scam.

- Chifney’s 200 guineas per annum pension was the price of the jockey’s silence.

- George abandoned Chifney to death in a debtors’ prison in 1807 because society had forgiven George, he needed the 200, and it would have been his word against Chifney’s.

Someone, write me a decent novel.

Anecnotes

- 1Mortimer, Onslow, & Willett’s Biographical Encyclopaedia of British Racing (1978) and other standard works incorrectly give the year of the Escape scandal as 1790 rather than 1791, and this is reflected in Wikipedia.

- 2Editorial note: The word “manner” is knowing, putting, keeping self and horse in the best of attitudes. This gives readiness, force, and quickness.

- 3But before anyone runs away with the idea that lightness is all, read this piece by John O’Leary.

- 4Which reminds me: neither can I find Trowbridge band Mechanical Horsetrough’s 1977 album Kaar-aaaap! It’s Mechanical Horsetrough!, which includes “The Ballad Of Red Rum.” Singer Alan Briars rings a bell via the Village Pump Folk Club. When he died,

Mrs Briars, 48, said: “Things were going a bit wrong and he was lying down with his eyes closed. I thought he was close. We had the radio on with the Bristol City match on and they scored in the last minute. Suddenly, he jumped up and cheered and punched the air with his fist. He was Alan until the end.”

Similar posts

Back soon

Comments