3 July 1837: The Swan, a Hull whaler, returns from the dead (the ice of the Davis Strait) bearing three whales

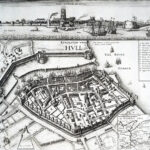

The Swan and Isabella, by Hull painter John Ward (Ward 1840ish).

Horace Baker Browne. 1912. The Story of the East Riding of Yorkshire. London: A. Brown and Sons. H.B. Browne appears to have been white-haired but alive in 1949 (see The Story of Whitby Museum), but I have found no trace thereafter. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

[A contemporary news sheet printed by Weston Howe, Lowgate, Hull.]

Arrival of The Swan from Davis’ Straits. 25 lives lost.

Yesterday, Monday July 3rd, in consequence of intelligence of the Swan having made the Humber, many thousands assembled at Southend, and were gratified with the sight of the long lost vessel whose reappearance was regarded as a sort of resurrection. On nearing the Humber Dock Basin, three loud and hearty cheers were given by the assembled multitude on shore, and answered from the Swan; this was at five o’clock, and during the two succeeding hours which elapsed whilst passing through the New and Junction Docks, until she was safely moored on the north side of the Old Dock, the thousands of spectators who thronged all the shipping and both sides of the docks, saluted her with many a cheer, appeared to suffer no abatement.

The survivors of her crew, including Captain Dring and his two sons, are all in tolerable health; the mate and one or two others look remarkable well, but the majority are still rather thin. No words can well describe the privations and sufferings to which the men have been exposed. The crew of the Swan originally consisted of 48 men, 24 of whom, including the captain and officers, sailed from Hull, and 21 were obtained at Shetland; of the Shetlandmen 11 have died, of our townsmen 7, and two others from Grimsby, while of the six who were received from the wreck of the Margaret, of London, but one survives. But for an unfortunate expedition, in which a party of men endeavoured unsuccessfully to reach a Danish settlement, the surgeon is of opinion that no more than 12 persons would hare died, and of those those who died of a scurvy it is proper to observe that their end approached very fast, when their spirits began to fail them after the melancholy affair.

During their confinement in the ice, divine worship was conducted every Sabbath, in a most orderly and impressive manner, by a pious Shetlander, the whole ship’s company engaging heartily in the service. The Swan has three fish, about 30 tuns [of oil]; twenty of the Duncombe’s men have arrived with her; the Duncombe has four fish, 60 tuns. The ships were parted in the Western ocean, about a fortnight ago, in lat. 53 N, and long. 40 W., since which they have not seen each other, but the arrival of the Duncombe is daily expected. We intend to recur to this subject next week, by which time we shall be able to give further and deeply interesting details of this most hazardous voyage.

The following are the names of the men lost: Thomas Haller, Henry Judge, Robert Derby [Brady?], Robert Collier, Daniel Knight, W. Walker, John Nuttal, John Stocks, R. Brady, (Englishmen), Gifford Wenwick, John Morris, Laurence Duncan, James Jameson, John Johnson, Magnus Harrison, James Moore, Peter Hunter, Thomas Hewson, William Harper, W. Bainton, James Jameson, Alex. Anderson, (Shetlandmen). The last five men belonged to the Margaret of London; Mr. Stoddard, the mate, being the only surviving one out of the boat’s crew. There is very little hope of a north passage this year.

Comment

Comment

Browne provides background and a sensational detail which I haven’t yet found elsewhere:

From 1772 to 1852 the Whaling Industry flourished. To the icy seas around Spitzbergen, or to the Greenland seas and the Davis Straits, there went each year ships of the Humber in number from three to sixty-five. Often they were unlucky, and had to return ‘clean’—that is, with nothing in their holds to repay their owners and their crews. Sometimes they were still more unlucky, and did not return at all, having been gripped in the ice or captured by French privateers. Out of ten ships that sailed from the Humber in 1775, six came back ‘clean,’ and two were lost.

One of the most disastrous years known was 1835, when five of the Hull ships were frozen up, three of them being eventually lost, one with all hands.

In the following year a Hull vessel, named the Swan, was frozen up much farther north than the whalers usually went; so that it was the midsummer of 1837 before she got free. Meanwhile she had been given up as lost; and on Sunday, July 2nd, a memorial service was held on the Dock Green, and a collection of £47 taken on behalf of the families of the crew. In the midst of the service, however, news arrived that the ‘missing’ vessel was entering the mouth of the Humber.

[…]

As a rule, however, a voyage resulted in fair profits for both owners and crews. The thirty-one ships that went to Greenland in 1821 took between them 204 whales, and the twenty-one that went to Davis Straits took 294 whales. These 498 ‘fish’ produced whalebone and oil to the value of £150,000. The average return per ship was here slightly lower than that for the whole period 1772–1852, which works out to £3,500 (Browne 1912).

If Browne is quoting 1912 equivalents, then £150,000 works out at £17.52 million in 2020, implying greater rationality in sailors than is suggested by an 1836 ballad referring to the tragedy of the previous winter:

With cheerful hearts they did depart, but little did they know,

What hardships great in Davis’s Straits they’d have to undergo.

(Venning 1985)

From the excellent Wikipedia entry on the Swan, which references inter alia the Coltish manuscript:

In 1836 Swan, Robert Dring, master, was the last of the Northern Fishery whalers to sail for the fisheries. In October she became ice-bound (beset) and did not get free until spring of 1837. In 1837 she was at Peterhead on 29 June, having gotten free of the ice on 24 May. The first whaler to sight Swan, on 14 May, was William and Ann. Swan was then some 30 miles west of Disco and Captain Stairton’s men refused to got to Swan’s assistance on the grounds that Swan was far off and they weren’t paid to do so. She was only able to get free because the crews of five whalers came upon her and sawed 3000 feet of heavy ice to get her out. The vessels also provided provisions, with one, Charlotte, Adamson, master, being particularly helpful. Then Dunscombe, owned by the same company as Swan, left off her fishing, provided 20 men to fill out Swan’s crew, and accompanied her home. Of Swan’s crew of 48 men, 20 had died, 14 of them in an attempt to reach a Danish colony in her boats. In addition to the men of her crew who died, five more men also died. Swan had taken on a boat of six men from the wrecked Jane and Mary, of London; of the six, only the mate survived.

However, undeterred,

On 18 August Swan, Dring, master, sailed from Hull to Petersburg. She returned on 14 November (Wikipedia contributors 2022).

Here are the final five days of the Swan’s logbook in this particular iteration, as transcribed by Sam Willis:

Sunday 17th of April. Strong breezes and fine clear weather. The ship drifting off to the westward. A great lane of water has broken out south of us but the ice in which we are froze up is quite stationary. Latitude by observation 70 degrees by 13 north.

Tuesday 18th of April. Light breezes and fine clear weather. A 270-gallon shake cut up this day for fuel. A few minutes before 12 this night Lawrence Duncan, Shetlander, expired having lingered a long time in a complete state of debility. Latitude by observations 70 degrees by 12 north.

Wednesday the 19th of April. Light breezes and fine clear weather. A 260-gallon shake, number 41, cut up for fuel. Average of thermometer twenty degrees. At 8am Daniel Knight’s remaining leg was amputated there being no chance of saving any part of the foot. This afternoon James Jameson, Shetlander, died in the last stage of scurvy. Thermometer twenty-six.

Thursday 28th of April. Light winds in fine warm weather. At noon called all hands and interred our poor shipmates. Middle and latter parts fine weather. The carpenter employed in making a jib boom. A 260-gallon shake cut up for fuel.

Friday the 21st [sic] of April. Light winds fine weather. The ship driving north very slowly. This afternoon Robert Brady, Seaman, died of scurvy and such was the filthy state of his bedclothes that they were thrown overboard.

(Willis 2021/04/26)

The authorities chose not to intervene as they had the previous winter, presumably on the principle of private gain, private pain:

Despite impassioned pleas from Hull, Dundee and Aberdeen, the government refused to mount another rescue attempt and a public controversy ensued. The Hull Packet asked ‘was there ever so cruel a mockery of sympathy as the Lords of the Admiralty and Lords of the Treasury have exhibited, in their proceedings relating to these unfortunate whalers?’

In March 1837 The Times fuelled the row by publishing the correspondence between the Admiralty and the northern ports, in which the Dundee and Aberdeen petitioners accused the Admiralty of sabotaging the previous year’s rescue attempt.

(Venning 1985)

Susan Capes of the Hull Maritime Museum wishes to draw your attention to this splendid model of the Swan:

Barry Venning convincingly suggests (Venning 1985) that Turner’s Whalers (boiling blubber) entangled in flaw ice, endeavouring to extricate themselves draws on his recollections of Ward’s painting:

(Turner 1846).

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

19 February 1866: The Diana, Hull’s first steam-assisted whaler and its last of any nature, leaves on its fateful voyage to the Arctic

19 February 1866: The Diana, Hull’s first steam-assisted whaler and its last of any nature, leaves on its fateful voyage to the Arctic 1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington

1 July 1840: The opening of the Hull and Selby Railway terminates the threat to Hull’s port from Goole, Scarborough and Bridlington

Comment

Comment

Smeaton’s scheme did not prosper. John Timperley:

Various schemes had been suggested for cleansing the dock of the mud brought in by the tide; one was by making reservoirs in the fortifications or old town ditches, with the requisite sluices, by means of which the mud was to be scoured out at low water; another by cutting a canal to the Humber, from the west end of the dock, where sluices had been provided, and put down for the purpose, when it was proposed to divert the ebb tide from the river Hull along the dock, and through the sluices and canal into the Humber, and so produce a current sufficient, with a little manual assistance, to carry away the mud. Both of these schemes were however abandoned, and the plan of a horse dredging machine adopted; this work began about four years after the Old dock was completed, and continued until after the opening of the Junction dock. The machine was contained in a square and flat bottomed vessel 61 feet 6 inches long, 22 feet 6 inches wide, and drawing 4 feet water: it at first had only eleven buckets, calculated to work in 14 feet water, in which state it remained till 1814, when two buckets were added so as to work in 17 feet water, and in 1827 a further addition of four buckets was made, giving seventeen altogether, which enabled it to work in the highest spring tides. The machine was attended by three men, and worked by two horses, which did it at first with ease, but since the addition of the last four buckets, the work has been exceedingly hard.

There were generally six mud boats employed in this dock before the Humber dock was made; since which there have been only four, containing, when fully laden, about 180 tons, and usually filled in about six or seven hours; they are then taken down the old harbour and discharged in the Humber at about a hundred fathoms beyond low water mark, after which they are brought back into the dock, sometimes in three or four hours, but generally more. The mud engine has been usually employed seven or eight months in the year, commencing work in April or May.

The quantity of mud raised prior to the opening of the Junction dock, varied from 12,000 to 29,000 tons, and averaged 19,000 tons per annum; except for a few years before the rebuilding of the Old lock, when, from the bad and leaky state of the gates, a greater supply of water was required for the dock, and the average yearly quantity was about 25,000 tons. As the Junction dock, and in part also the Humber dock, are now supplied from this source, a greater quantity of water flows through the Old dock, and the mud removed has of late been about 23,000 tons a year.

It may be observed, that the greatest quantity of mud is brought into the dock during spring tides, and particularly in dry seasons, when there is not much fresh water in the Hull; in neap tides, and during freshes in the river, very little mud comes in (Timperley 1842).

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter