15 May 1890: A Liverpudlian company – now ruined – finds on appeal that the consent of its Halifax lender isn’t needed to sue the Sowerby Bridge flour coop for patent piracy

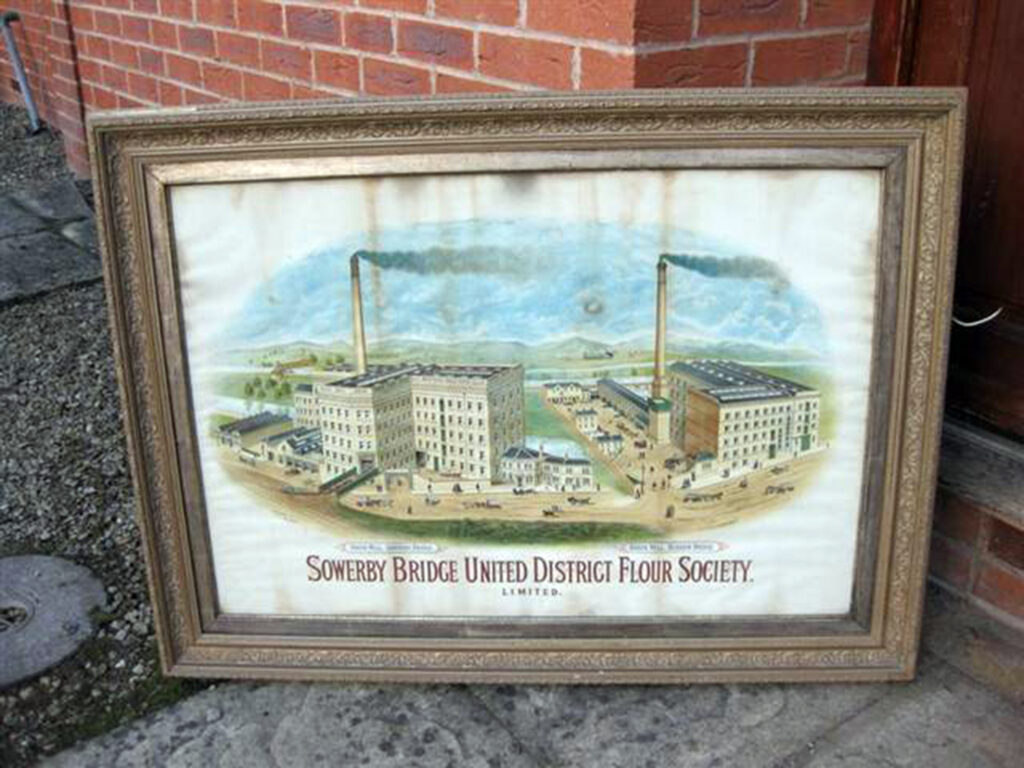

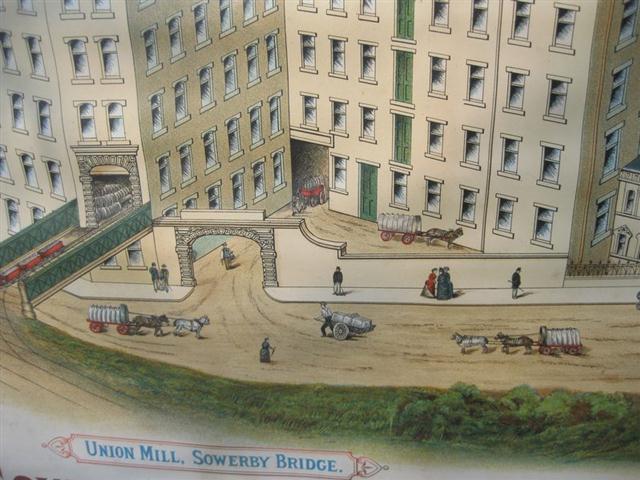

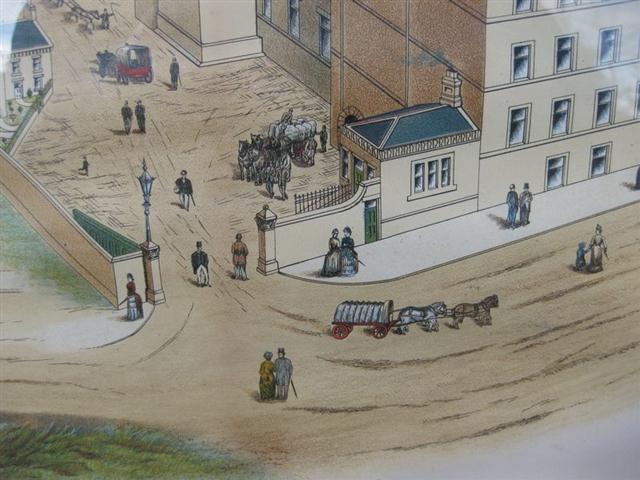

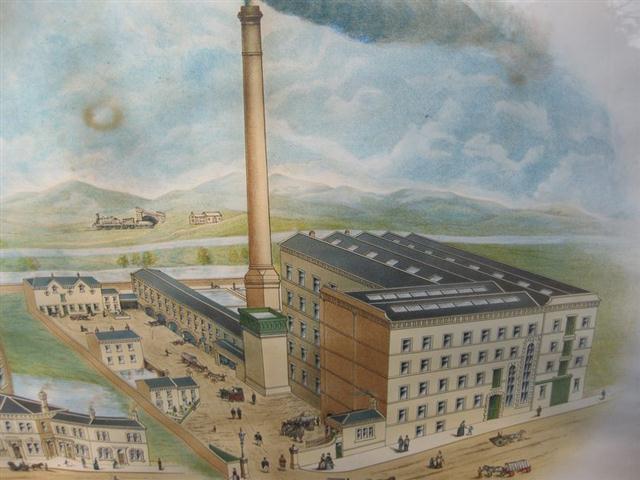

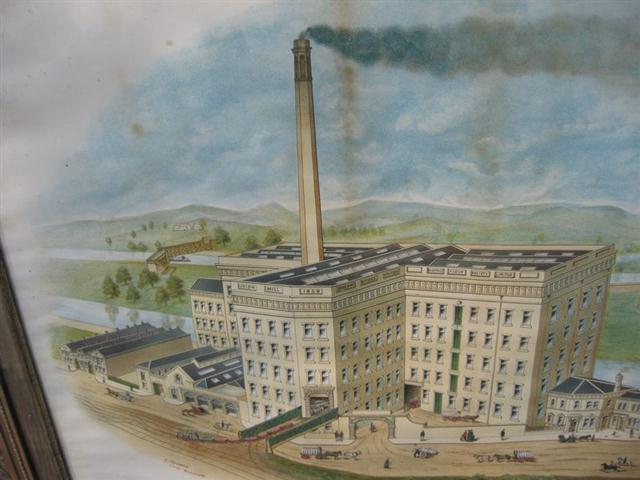

A sales photo of an advert for Sowerby Bridge United District Flour Society, showing Union Mill, Sowerby Bridge (left) and Breck Mill, Hebden Bridge (Sowerby Bridge United District Flour Society 1911).

Leeds Mercury. 1890/05/16. Van Gelder and Co.’s Patent Action. Leeds. Get it:

.Unedited excerpt

If an excerpt is used in the book, it will be shorter, edited and, where applicable, translated.

In the Court of Appeal yesterday, consisting of Lords Justices Cotton, Lindley, and Bowen, judgment was delivered in the action of Van Gelder, Apsimon, and Co. Limited v. The Sowerby Bridge United District Flour Society Limited. The plaintiff company, now in liquidation, are the assignees of an invention patented by Pieter van Gelder for improvements in the method of cleaning grain by a sieving apparatus. The plaintiff company are the assignees of the patent, and the action was brought against the defendant company to restrain them from infringing the patent, and for damages consequent on alleged infringement. The plaintiff company executed mortgages on the patent to the Halifax Joint Stock Banking Company to secure advances, and there were subsequent mortgages. When the action came before Mr. Justice Kekewich in January last the Attorney-General, on behalf of the defendants, objected that under Sections 46 and 87 of the Patents Act the plaintiff company as assignees could not sue without the mortgagees being made parties to the action. Mr. Justice Kekewich gave the plaintiffs an opportunity of making the mortgagees parties, but they refused their consent, and on the 1st February his Lordship dismissed the plaintiffs’ action with costs. Against that order the plaintiffs appealed.

Lord Justice Cotton, in the course of his judgment, said in his opinion there was nothing in Sections 46 and 87 of the Patents Act to prevent the registered owners of a patent from protecting their property without adding their mortgagees as parties to the action.

Lord Justice Lindley said the proposition before the Court was serious, startling, and novel, and if Mr. Justice Kekewich was right, then the mortgagor of a patent, unlike the mortgagor of any other kind of property, could obtain no relief against any person injuring or destroying his property unless he could induce his mortgagees to become a party to the action, or unless he could get rid of them by paying them off. This was a startling proposition; and was it sound? Tried by every decided principle of equity, it was unsound, and it certainly was startling to be told that a mortgagor, by mortgaging his property, was to be deprived of protecting it unless he could induce his mortgagees to join him.

Lord Justice Bowen concurred.

The judgment of the Court below was therefore reversed, the plaintiffs to have the costs of appeal and the costs thrown away in the Court below. As the action for infringement may now be tried, the Court gave the defendants liberty at any stage of the action to apply to the Court to have the mortgagees or any of them made defendants in the action.

Comment

Comment

The action seems to have ended there – presumably ownership of patent no. 2,470 passed to Halifax Joint Stock Banking Company, who may not have thought the claim valid or worth pursuing, or to another creditor. Why did the Halifax bank resist being made a party to the action in January 1890? Perhaps they feared pumping good money to London lawyers after bad money lost to Liverpool tech entrepreneurs. Perhaps local personal and/or business ties were important – how close were they? Bank docs tend to survive, so I hope someone will tell me.

Detail from The Times (Kekewich was notoriously incompetent – see his WP entry):

The plaintiff company claimed an injunction and damages in respect of the alleged infringement of letters patent, 1878, No. 2,470, for “improvements in apparatus for separating substances by means of sieves, and in the mode of operating parts of the same,” granted to Mr. P. van Gelder, who had assigned the patent to the plaintiff company. The assignment to them was registered on February 22, 1886, and on the same day a mortgage of the patent by the plaintiff company to the Halifax Joint Stock Banking Company was registered. The mortgage was in the form of an absolute assignment subject to redemption, with a proviso that the mortgagor should not be at liberty to grant licences. Four other mortgages were also subsequently registered, each of them being by way of assignment…

[Lord Justice Cotton:] The Attorney-General relied on sections 46 and 87. Section 46 had no bearing on the question. If the general law applied, his Lordship would say that an assignee of a patent was entitled to the benefit of the patent, even though he had mortgaged it. In equity a mortgage was looked upon as security for a debt; and subject to the charge the mortgagor was entitled to the benefit of his property. Then section 87 was relied on. The Court had had the benefit of hearing what took place before Mr. Justice Kekewich with regard to the registration, and it appeared that the plaintiffs were placed on the register on the 22d of February, 1886, as assignees. There was also on the same day a registration of the mortgage granted to the bank – it was unnecessary to refer to the other mortgages as they were all registered in the same way – but the bank were registered as mortgagees and not as assignees, although the mortgage was by assignment, and the officer from the Patent Office said that it was not the practice to register mortgages, even though the mortgage was by way of assignment, as assignees, because the assignee was regarded as the proprietor. In his Lordship’s opinion that was quite right. It was therefore unnecessary to consider the argument founded on section 87.

(Times 1890/05/16)

Other events of interest:

- Thomas ApSimon got married on 21/11/1877 to Anna Thompson, daughter of a wealthy Ulster-New York-Liverpool hatter, Joseph Thompson (1802/3-82). She probably came with a dowry sufficient to finance new activities such as the partnership with Pieter van Gelder following the collapse of John Hawleigh Smith & Co in mid-1878. I’m guessing the Bala drapery hoard of his father Simon Jones (1805-73) had already been pretty much exhausted.

- Van Gelder, ApSimon, and Co. Limited was incorporated on July 17th, 1885: “This is the conversion to a company of the business of mill engineers, millwrights, and machine makers, carried on by Messrs. Van Gelder and Apsimon, at Victoria Works, Sowerby Bridge, York, and 3, Old Ropery, Liverpool.” The share offering (4,000 x £10) was undersubscribed by more than 50%: Thomas ApSimon (Birkdale, milling engineer) took 800, Pieter van Gelder (Sowerby Bridge, milling engineer) 900 (cash or by assigning other patents?), others 87, giving capital of roughly £1,817,378m (January 2023) (Engineer 1885/07/31). Perhaps this lack of enthusiasm and cash explains why recourse was made to the Halifax bank, and why the company chose the risky strategy of litigating against the Sowerby Bridge coop.

- The fortunes of Thomas ApSimon may be judged from his houses: 17 Trafalgar Road, Birkdale, Southport (1885-87); Willow Hall, Sowerby Bridge (1887-91); 20 North Road, West Kirby (1891-96).

- Despite the “liquidation,” this suggests that Van Gelder and ApSimon were still at it in 1892, presumably reverting to their pre-1885 unincorporated arrangement, perhaps until Van Gelder found something better.

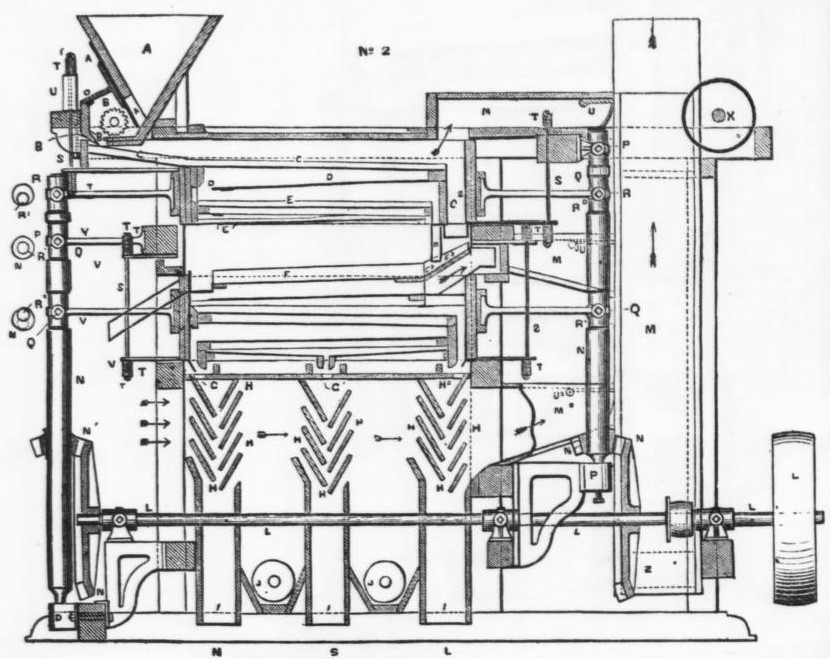

I’d like to know more about Pieter van Gelder, who appears in The Engineer 1875-1903, and who was I believe born Dutch but naturalised in the 1880s. Here’s his double eccentric separator – marketed in association with Thomas ApSimon:

More photos of the coop ad:

Something to say? Get in touch

Similar

14 December 1892: Experts tell the High Court that electromagnetic interference from Leeds’s 1891 overhead electric tramway to Roundhay – the nation’s first – has brought down the local telephone service

14 December 1892: Experts tell the High Court that electromagnetic interference from Leeds’s 1891 overhead electric tramway to Roundhay – the nation’s first – has brought down the local telephone service

Comment

Comment

They were duly deployed:

Saturday 18 August [Halifax] Mending my stocking tops for an hour … Just before I went out this afternoon, George took the hedgehogs from the back room & put them loose under the great yew tree.

But that is the last we hear of them. Perhaps they found the West Riding unbearable and set off to scuttle the 60 miles to their home in the East.

Something to say? Get in touch

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter