22 September 1896: Clifford Allbutt on the threat to industry from anti-scientific manufacturers and workers, and colonialism

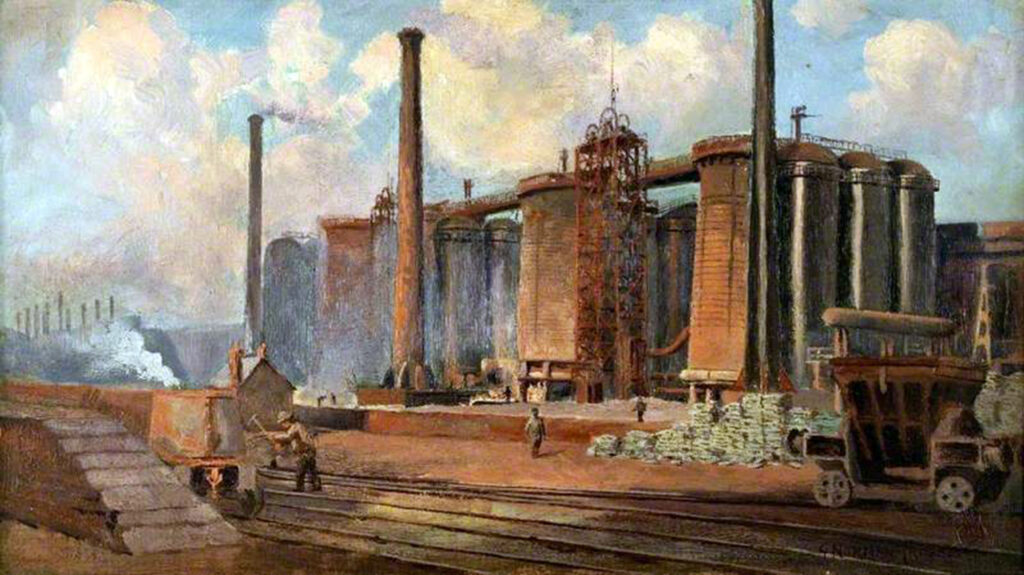

The Gjers Wills’ Ayresome ironworks in Middlesbrough around the turn of the century (Norman-Crosse 1900ish).

T. Clifford Allbutt. 1896/09/22. Science in the Old Universities. Times. London. Get it:

.Excerpt

It is not only that manufacturers ignore science or shrink from the trouble of it, but also that they have a positive aversion from it: the intrusion of the scientific spirit makes them fretful and even angry. They believe this spirit to be destructive of the dexterity, smartness, and shrewdness in the affairs of the day to which they believe, and rightly believe, that their own success was due. They cannot see that their pioneering days needed different qualities from those needed now, when manual skill and rule-of-thumb methods are no longer sufficient. Thus it is that manufacturers bring up their sons in the very worst way conceivable. Those young men have not had the education of fighting out all the problems of the business life as their fathers had; yet the fathers dread the infection of the “unpractical” scientific education, and look for the victories which they think even in trade are still won in the playing-fields of Eton. Bear with me while I refer to the further, but not smaller, difficulty – namely, the British working man. Instead of the 70 chemists working in many a factory in Germany, the firms in Lancashire and Yorkshire who employ even one chemist on laboratory work may be counted well within the resources of one hand. Scientific methods, where introduced, have been brought in with the greatest caution, and at the risk that foremen first and then the rank and file of workmen would throw down their tools. There is no want of original genius in us, but it is so much mingled with a pioneering and adventurous temper that it is doubtful whether we shall not refuse to practise the fine economies of science, and prefer rather to throw our energies into new countries, as long as these last! An able engineer, the head of large works in the north of England, told me, not a year ago, that the only way in which he could introduce a new labour-saving appliance was to throw it down in the shop with an indifferent and sceptical air; after it had lain there for some weeks, some foreman would take a fancy to it and bring it forward as an adoption of his own.

Comment

Comment

I haven’t read the Thomas Thorpe piece which triggered Allbutt, but the Leeds industrialist James Kitson II rebutted Allbutt’s claims, and Allbutt gave as good as he got. Etsuo Abé’s analysis of the decline of Middlesbrough iron- and steelmakers Bolckow, Vaughan & Co. is a textbook example of what Allbutt was describing: while they were comparatively early adopters in the 1870s of the Bessemer process, which allowed the replacement in rails of wrought iron by mass-produced mild steel, it wasn’t until just before World War I that they made a full transition from basic Bessemer converters to the basic open hearth furnaces which had been producing high quality steel for ship plates and increasingly rails in the United States and Germany since the 1890s (Abé 1996).

Something to say? Get in touch

Original

SCIENCE IN THE OLD UNIVERSITIES.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

Sir, I have waited in the hope that an abler hand than mine would make some reply to the judgment pronounced by Dr. Thorpe in your columns and in those of a contemporary upon the old Universities. I had almost called it an attack rather than a judgment, and I think that I should not have been wrong if I had used that word. For as a judgment it is harsh and indiscriminate. and, moreover, leaves an untruthful impression which Dr. Thorpe may regret, but which he has not been careful to avoid.

I do not stand alone in saying that under the subject of chemistry Dr. Thorpe has pronounced or implied sweeping condemnation of all the scientific work at Oxford and Cambridge. I call this judgment an indiscriminate attack – first, because he has not considered whether there are any special causes arresting the progress of chemical studies here; and, secondly, because he has conveyed an impression that all other departments of physical science are in like defect, without staying to consider whether this impression te a mistaken one. Oxford is well able to take care of itself; I shall deal with Cambridge only.

It is alleged that Cambridge is occupied with literature, philosophy, and ethics, which do not lead to commercial prosperity, to the neglect of studies which are good for trade; a monstrous attitude, no doubt, if true!

Let us turn for a moment to look at the facts. Dr. Thorpe gauges Cambridge by the records of scientific work issuing from its laboratories; these, he says, are exiguous. And he leaves the reader to infer that this barrenness is characteristic of all the travail of natural science in Cambridge.

Now I do not hesitate to say that such an inference is a very unfair one. To the position of chemistry I shall refer presently, and I will not dwell on the Cambridge school of mathematics – a study which lies, as Dr. Thorpe will admit, at the root of all positive knowledge. But I will turn to the Cavendish laboratory of physics, to the engineering laboratory, to the great schools of biology – of anatomy, of physiology, of morphology, and (although its work is for a time arrested by the illness of its professor) of pathology; and I will ask whether the researches issuing from these schools are exiguous? I will not do the respective professors and lecturers in these great departments the injustice of supposing that to name them personally is necessary even for the information of the general reader. I may add that a laboratory of pharmacology has recently been established, and has already begun to give a good account of itself. Does this look as if the University was supine in science, even if we make no allowance for the narrowness of revenue which is now starving every department?

We will now turn to Dr. Thorpe’s own subject of chemistry. Why is it, if we assume it to be the case, that so little work is recorded in this department? That there is some activity in the study is obvious, for not only is the University laboratory full of students, but there are busy laboratories in Caius and Sidney Colleges also. And I may remind the reader that Cambridge has done more perhaps than any other University to develop a school of agricultural chemistry, and this not without success. But to leave extenuations and to return to the main charge. Why are the returns of research not greater in chemistry? The reply is a simple one – because for Englishmen there is no career in chemistry! Thus it is that these laboratories are full, but of students who require some knowledge of chemistry for other callings, such as medicine, engineering, physics, physiology, and so forth; or again as a valuable subject to take up for the Natural Science Tripos; but by no means for its primary pursuit. And this, I repeat, is because there is no career in chemistry! A few men here deeply interested in the science have pursued it; and of these some are able to make a livelihood as Fellows and teachers; or, again, as workers in the chemical aspects of other branches of study, such as physiology. But if these posts are to be called careers they can occupy but a very few. What is the consequence of this state of things? It is this – that tutors advise their science pupils to take up any study, as a main pursuit, rather than chemistry. I am rarely asked to advise on this matter, but when asked I give the same advice. Now, why is this? Because the English manufacturer, master or man, is not likely to be enlightened during any space of time which can modify our calculations of the prospects of the present generation of undergraduates. The few men now turned out as accomplished chemists are articles for which in England there is no demand; these men are disappointed; they have to turn their abilities in other directions, and they actively discourage younger men from repeating their own mistake. The work of engineers lies so close to physics and to mathematics that in them the distrust of scientific men is less than it was; and, obstinate as it still is, it is slowly melting away; there is a career for young scientific engineers: but the time of the chemists is yet far off. My friend Dr. Thorpe knows the manufacturing districts of the north of England well, but not so well as I do, who was born in Dewsbury, and have lived most of my adult life in Leeds. Still he must be aware of the spirit of opposition in almost all manufacturers to any introduction of scientific studies. It is not only that, as a body (I do not forget the few eminent exceptions), they ignore science, or shrink from the trouble of it; but also that they have a positive aversion from it: the intrusion of the scientific spirit makes them fretful and even angry. They believe this spirit to be destructive of the dexterity, smartness, and shrewdness in the affairs of the day to which they believe, and rightly believe, that their own success was due. They cannot see that their pioneering days needed different qualities from those needed now, when manual skill and rule-of-thumb methods are no longer sufficient. Thus it is that manufacturers bring up their sons in the very worst way conceivable. Those young men have not had the education of fighting out all the problems of the business life as their fathers had; yet the fathers dread the infection of the “unpractical” scientific education, and look for the victories which they think even in trade are still won in the playing-fields of Eton; thus they move in a vicious circle. The sons grow up at least as stupid in the face of scientific advance as their fathers, and have not the discipline which circumstances gave to the older generation.

What is the consequence? I advise a gentleman who has to place large contracts to visit the works of personal friends of my own – an engineering firm of the highest traditional reputation. He does so, and writes to me:- “I made a civil escape from your friends’ works, because I was in them 14 years ago and to-day! I find there almost the same tools as I saw on a visit 14 years ago. I drew my own conclusions.”

Bear with me while I refer to the further, but not smaller, difficulty – namely, the British working man. Instead of the 70 chemists working in many a factory in Germany, the firms in Lancashire and Yorkshire who employ even one chemist on laboratory work may be counted well within the resources of one hand. I happen to know of one firm only. Why is this, when it is known that the one English firm to which I refer within one year of engaging a chemist, a German I regret to say, learned so much of new processes that they were able to keep actively at work during a winter when other firms in the same business were almost closed? Because other firms dare not introduce scientific methods. These methods, where introduced, have been brought in with the greatest caution, and at the risk that foremen first and then the rank and file of workmen would throw down their tools. The men might be beaten, but few employers will face the risk of closing their works; they had rather potter on with things as they are. The British artisan is the most skilful workman in the world, and he knows it; an English or Scotch fitter can turn out work better than any other work in Europe, and his machines therefore outlast those of any other country. But it is a matter for very serious doubt whether the Briton, master or man, has the elasticity of mind to turn to new methods. There is no want of original genius in us, but it is so much mingled with a pioneering and adventurous temper that it is doubtful whether we shall not refuse to practise the fine economies of science, and prefer rather to throw our energies into new countries, as long as these last! The example of Lord Kelvin – a Cambridge graduate, by the way – of Lord Armstrong, of Sir Lowthian Bell, and happily many other scientific men, who have combined science with boldness of adventure, may be catching; at any rate, it is sorely needed. An able engineer, the head of large works in the north of England, told me, not a year ago, that the only way in which he could introduce a new labour-saving appliance was to throw it down in the shop with an indifferent and sceptical air; after it had lain there for some weeks, some foreman would take a fancy to it and bring it forward as an adoption of his own.

A recent correspondent of The Times said that to give technical education to the workman was as idle a scheme as to educate Tommy Atkins in strategy. The error of this reasoning has been shown by others; and I will, therefore, content myself with saying that if the Tommy Atkins of the shops is not brought into some sort of acceptance of a new spirit in manufacture the prospects of British trade are bad. It is not attainments that he needs, but some solution of the obstinate conservatism and reliance on personal resources which at present make him a greater difficulty in the way of employers than their own distrust of abstract principles.

To illustrate the vital importance of the first principles which, rather than technical skill, should be taught at Universities, permit me in conclusion to give two examples.

Twenty years ago a friend of my own, a fair mathematician and a most acute person, on visiting a large engineering works in the north of England saw lying in heaps cogwheels returned for repairs of fractured teeth. He exclaimed that this should not be, for Professor Willis, of Cambridge, had calculated out the dimensions of these toothed wheels, and had published them, years before, for all whom it might concern. The suggestion that a University professor could know more of such matters than a “practical man” was scouted. But two or three years later this argument was renewed, and my friend sent Willis’s book as a present to the firm, begging them to place it in the drawing office. This firm grudgingly admitted, at a much later date, that they had saved large sums of money by the study of Willin’s book, not only in respect of the cogwheels, but in other matters also.

Once more, in respect of the uselessness of the “old Universities,” contemptuously so-called. An eminent London physician, not himself a Cambridge man, told me but two months ago that a patient of his – a Thames engineer – told to him this story. This engineer had accepted a contract for ten large engines; the first was built, but it failed to work up to contract standard. The disappointment and bewilderment in the shop were great foremen were appealed to in vain; it was alleged that all the conditions had been observed and that the failure, which meant the loss of a large contract, was inexplicable. In the midst of the excitement a young Cambridge graduate, who perhaps had never been in a large shop before, came on the scene and found his way into the group. After hearing the facts, he diffidently suggested that the error might lie in such and such parts, and that he had lecture notes which might be of some help. The head of the firm put him promptly into a cab, telling him to bring all his notes and books back with him. He returned and found the full explanation of the failure. I was told that the error lay in some loss of heat by the case-hardening of certain plates; but, whatever it were, if young men are thus trained in the “old Universities” their part in life is not to be sneered at as by ” Y.” in a letter in your columns of September 16.

I am, Sir, yours,

T. CLIFFORD ALLBUTT.

St. Radegund’s, Cambridge, September.

2256 words.

Similar

Search

Donate

Music & books

Place-People-Play: Childcare (and the Kazookestra) on the Headingley/Weetwood borders next to Meanwood Park.

Music from and about Yorkshire by Leeds's Singing Organ-Grinder.

Bluesky

Bluesky Extwitter

Extwitter