Category: Empire

1500-1700

Columbus was a proto-Judenstaatler, says someone

But a joke I have just cobbled together suggests otherwise.

Interchangeability of nominative and genitive forms of Spanish patronymics?

I’m thinking of examples like Álvarez/Álvaro, Alves/ Alves, Benítez/Benito, Díaz/Diego, Domínguez/Domingo, Fernández/Fernando, Giménez/Ximeno, Gómez/Guillermo, González/Gonzalo, Gutiérrez/Gutierre, Henríquez/Henrique, Ibáñez/Juan, Juánez/Juan, López/Lope, Márquez/Marco, Martínez/Martín, Menéndez/Menendo, Muñoz/Muño, Núñez/Nuño, Ordóñez/Ordoño, Ortiz/Ortún, Peláez/Pelayo, Pérez/Pere, Ramírez/Ramiro, Rodríguez/Rodrigo, Ruiz/Ruy, Sánchez/Sancho, Suárez/Suero, Vázquez/Vasco, Velázquez/Velasco.

Hot news

Although this fact may not have occurred to American journalists, living in monolingual paradise, it’s hard choosing names in a global market where everything means something bad to someone, somewhere.

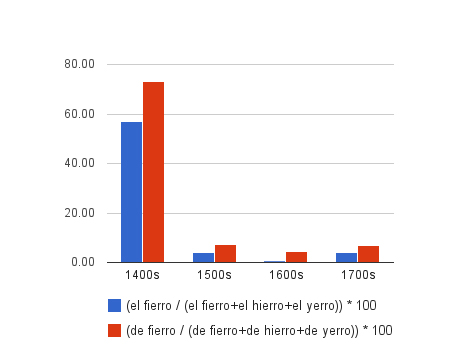

Fierro favoured slightly over hierro/yerro after vowel in early modern Spanish?

It sounds better.

“Let’s roll!” in Spanish

“¡Dale al asno!” ruled out in the first round.

Does historical reenactment extend to speech?

Early modern editing for the creative anachronism market: judicious modernisation, sympathetically documented transcription, or Talk Like A Pirate?

Presenting authorial & editorial notes in a Kindle edition of a 16th century bilingual text

Hints gratefully received…

Paradise and town-planning

The Turks and Jews of Istanbul demonstrate that co-existence is not impossible.

The storks of war

A fragment from Italo Calvino’s quasi-17th century folk romance, Il visconte dimezzato/The cloven viscount, uses storks as a portent of battle. Several unconnected 2nd century Greek accounts might appear to do the same, perhaps particularly if one’s a lazy sod and doesn’t read anything but scraps of stuff on Google Books.

![No woman, still die: a travesty of Henry Heath's <a href='http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=1661443&partid=1&searchText=ahithophel+in+the+dumps&fromADBC=ad&toADBC=ad&titleSubject=on&physicalAttribute=on&numpages=10&images=on&orig=%2fresearch%2fsearch_the_collection_database.aspx¤tPage=1'>Ahithophel [Wellington] in the dumps</a>. No woman, still die: a travesty of Henry Heath's <a href='http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=1661443&partid=1&searchText=ahithophel+in+the+dumps&fromADBC=ad&toADBC=ad&titleSubject=on&physicalAttribute=on&numpages=10&images=on&orig=%2fresearch%2fsearch_the_collection_database.aspx¤tPage=1'>Ahithophel [Wellington] in the dumps</a>.](https://lh6.googleusercontent.com/-4_GUKxjp4-Q/TnMWud5xHfI/AAAAAAAAw6E/Gpm83jNs_cw/s1000/AN00684413_001_l.jpg)