The sheep and goats above have just arrived back in Plan from low pastures to spend the summer in the mountains, rather like schoolchildren coming back from a language exchange. Joaquín Costa’s Colectivismo agrario en España (1898), available in full on Corde, contains a number of accounts of communal herding arrangements in the Pyrenees:

The town of Sallent, in the valley of the same name, … sends up to the pass the cattle of all the residents in the care of a communal herdsman. (Verbal communication from Félix Gazo, lawyer at Boltaña.)

Gistaín, another village in the Aragonese Pyrenees, engaged exclusively in livestock production, also forms a common flock from the animals or flocks of all residents , which graze the village’s common and private pastures. To avoid confusion between the animals belonging to individual farmers, they are marked with branding irons [because nothing more likely occurs to me, I take preguntas to refer to the question mark, branding with which is a not uncommon metaphor … in humans, in English] or special marks imprinted with hot pitch. As the district is very extensive and the flock is thousands strong, administration is facilitated by dividing both the former and the latter into three sections, which function independently of one another: the general administration is charged to three individuals, one for each section, who at the end of the season settle accounts for the herdsboys, head herdsmen [rabadanes],

dogs, salt, hut-keeper [cabañero] (herd donkey [burro hatero, another Aragonism, doomed by a lack of interest in its morphology]), winter pastures on low ground, and other expenses, to be exacted at so much per head. (Communication from Joaquín Bielsa Mur of Gistain.)Benavente, in the same province of Huesca, provides for other villages a model of mixed agriculture (cereals, vines, olives, horticulture) and bare mountain land or meadow for pasture: they note the relative herbiage of the holdings of each resident and on that basis calculate the number of sheep each may admit into the communal flock, be it six, eight, fifteen or thirty; they employ a shepherd and dog for eight or nine months; they maintain them both, and where appropriate the chief shepherd or assistant, in turn, giving them hot suppers in their homes at night and preparing their panniers for the morrow, a certain number of days per turn, proportional to the number of head each has in the communal flock; and in similar proportion they pay the salary of the shepherd and the expenses of transhumance to the high Pyrenees during the summer.

And so on. Here (local copy) is an interesting OCR-ed document from 1855 which I found lying around in a folder on the site of the Spanish Ministry of Taxation and Stopping Johnny Foreigner Buying Spanish Companies which details the costs of such undertakings.

Costa served as an inspiration for a host of twentieth century collectivisers of both left and right (Aragonese falangists and socialists alike seem to have regarded him as something of a regional deity), but this kind of practice has more or less completely died out now. I think there’s only one communal herdsman left in all the six/seven villages in this valley, J in Sº, who works in the mountains at the head of the next valley to the east with cattle in the summer. It’s increasingly difficult to get hold of professional herdsmen at what is regarded as a sensible wage, and vastly improved transport means that farmers can drive their 4×4 up to 1500m every morning after coffee and spend a few hours with the animals when otherwise they’d be sitting at home doing nothing. I’ve been asked if I’d consider it, but there’s no WiFi up there and I don’t like giving injections.

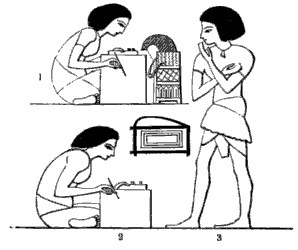

Finally, here from John Gardner Wilkinson’s A second series of the manners and customs of the Ancient Egyptians (1841) is a head shepherd accounting to scribes on an estate in Thebes:

The book contains more woodcuts on this theme and is most entertaining.

Similar posts

Back soon

Other factors include better healthcare, cheaper fencing solutions, …

I like the sheep placenta ad.

Beats me why anyone would fight mum for the placenta when there’s a delicious baby lamb lying there.