The Directorate-General of Democratic Memory (sic)), part of the Generalitat run by the communists until the regional elections last year, records 52 deaths 74 years ago in a Civil War bombing raid, a figure in the same park as the then Catalanist-Stalinist government’s communiqué, but which in a press release for some public ceremony they raise to 87 without submitting further documentation. Taking as ever a more positive view, Imperio: diario de Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS, conceals the bombing of “military targets” in Barcelona (victims ~0) beneath important news of the decapitation of the statue of Lope de Vega in Madrid by “the Marxist hordes.” On the other hand, in Australia The Age, weary, broke and perhaps easy prey for propagandists, bought some loon’s estimated 300 civilian deaths.

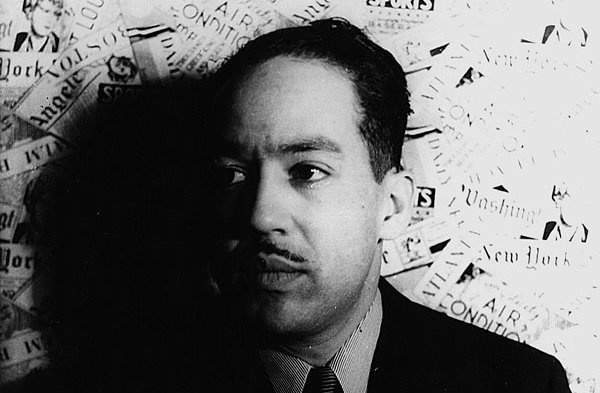

But I don’t think even we creative anachronists really care very much about these dates and numbers any longer. All that really lingers of this first great raid is the poem “Air raid: Barcelona” by the black American communist writer, Langston Hughes, published in Esquire in 1938:

Black smoke of sound

Curls against the midnight sky.

Deeper than a whistle,

Louder than a cry,

Worse than a scream

Tangled in the wail

Of a nightmare dream,

The siren

Of the air raid sounds.

Flames and bombs and

Death in the ear!

The siren announces

Planes drawing near.

Down from bedrooms

Stumble women in gowns.

Men, half-dressed,

Carrying children rush down.

Up in the sky-lanes

Against the stars

A flock of death birds

Whose wings are steel bars

Fill the sky with a low dull roar

Of a plane,

two planes,

three planes,

five planes,

or more.

The anti-aircraft guns bark into space.

The searchlights make wounds

On the night's dark face.

The siren's wild cry

Like a hollow scream

Echoes out of hell in a nightmare dream.

Then the BOMBS fall!

All other noises are nothing at all

When the first BOMBS fall.

All other noises are suddenly still

When the BOMBS fall.

All other noises are deathly still

As blood spatters the wall

And the whirling sound

Of the iron star of death

Comes hurtling down.

No other noises can be heard

As a child's life goes up

In the night like a bird.

Swift pursuit planes

Dart over the town,

Steel bullets fly

Slitting the starry silk

Of the sky:

A bomber's brought down

In flames orange and blue,

And the night's all red

Like blood, too.

The last BOMB falls.

The death birds wheel East

To their lairs again

Leaving iron eggs

In the streets of Spain.

With wings like black cubes

Against the far dawn,

The stench of their passage

Remains when they're gone.

In what was a courtyard

A child weeps alone.

Men uncover bodies

From ruins of stone.

Poetry ain’t history, and no heavy bombardments or fatalities were recorded during Hughes’ brief stay in Barcelona during his 6-week visit in Spain in October and November 1937. Rather, I guess the factual sources for his totemising of Barcelona’s suffering were the light raid he experienced on the night of October 3-4, journalised on October 23 in Carl Murphy’s Baltimore Afro-American, perhaps combined with ideas or stories about that raid or with possible (but afaik unrecorded) experiences of air attacks in Valencia or Madrid.

I think there’s a general problem with the relationship between ideas and reality in Hughes’ work in the 1930s, where his eyes and ears have either betrayed him or not been allowed to do their work. There’s a nice little example of the former here is his neutralisation of the siren–for working men and women that most potent of industrial icons–by anthropomorphing it from regular, known machine-sound…

I had just barely gotten to my room and had begun to undress when the low extended wail of the siren began… In an ever increasing wail the siren sounded louder and louder, droning its deathly warning.

… into irregular, unconvincing biophony:

The siren’s wild cry

Like a hollow scream

Most of Hughes’ Spanish work first appeared in the Baltimore Afro-American, an essentially NAACP entity which continued to publish articles on the conflict by Hughes for some months after his departure, and which expected to find in Spain

not only the center of the European conflagration, but [also] a battle ground and a country in which all races are fusing under the heat of conflict.

The Spanish melting pot, into which has already been poured the blood of many races, including Indian and African, is being stirred again, and this time the German, Italian, the French, the English, the Moor and Algerian from Northern Africa, and colored men from America and other sections of the world, are being hurled into the vortex.

As Mr. Hughes’s articles … indicate, the Spanish situation is but a prophecy of what all Europe is approaching, and from this angle colored men and women here in America and throughout the world will be interested.

In addition to the profound clash of economic, political, territorial and racial interests, there is also the age-old question of racial relations.

If for the Afro this expedition was conceived as a follow-up to the négritude of Hughes’ “Air Raid Over Harlem,” written in response to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, another of his sponsors had a rather more complex agenda.

Despite his subsequent denials, Hughes had had a close relationship with the Comintern cultural machine since the early 1930s. 1932 saw the publication by a Soviet-run trade union based in the Rothesoodstrasse in the Hamburg port of Hughes’ vulgar Stalinist Ãœbermensch rant, “Goodbye, Christ”, which was rediscovered in 1941 by white segregationist Christians and disowned by him. In it the “I” figure

was the newly liberated peasant of the state collectives I had seen in Russia, merged with those American colored workers of the depression period who believed in the Soviet dream and the hope it held out for a solution of their racial and economic difficulties… [other work includes] many verses most sympathetic to the true Christian spirit…

Now … having left the terrain of ‘the radical at twenty’ [he was actually 30 when it was published] to approach the ‘conservative of forty,’ I would not and could not write ‘Goodbye, Christ,’ desiring no longer to epater le bourgeois…

The explosives of war do not care whose hands fashion them. Certainly, both Marxists and Christians can be cruel.

Would that Christ came back to save us all. We do not know how to save ourselves.

In June 1932 he sailed to Russia with 22 other African Americans to make a film, Black and White, portraying the crucifixion of Negroes in US. The project collapsed almost immediately because, pace the Afro, of “unsuitable American Negroes” and the mighty American dollar.

Others left, but Hughes stayed on to work for the Soviet government on Izvestia, which sent him to the Uzbek Republic for four months. His 1934 anthology, A Negro looks at Soviet Central Asia, portrays a race relations utopia of Russian Christian colonists the Muslim locals at odds with subsequent accounts, and curiously fails to find traces of the mass killings conducted over the preceding couple of years in order to facilitate collectivisation, nor the widespread hunger which was its result.

Although ethnic cleansing of the Ukrainian Germans and Poles had commenced in autumn 1936, Stalin’s slaughter of inconvenient minorities (including American emigrés) began in earnest in summer 1937. But that summer Hughes again demonstrated a phenomenal capacity to avoid mixing poetic truths with uncomfortable facts and joined the Stalinist Guerra Civil literary roadshow:

At the Paris sessions of the Second International Writers Congress against Fascism, Hughes gave an important address in which he proclaimed that American Negroes understood and opposed fascism since they lived with it every day. Recent events in Ethiopia, Germany, China, Italy, and Spain only showed that the “economic and social discrimination” directed against blacks in America was now being applied to oppressed groups worldwide…

Hughes presumably didn’t prolong his stay in Barcelona because both the Afro and the Kremlin were presumably more interested in the progress of the black and generally communist Abraham Lincoln Brigade on central battlefields.

However, the Soviet propaganda dream of men of colour and men in overalls fighting Spanish bosses, and providing a model for their American counterparts, was rudely shattered when–as Hughes rapidly discovered–it turned out that the major contribution to the war by brown-skinned men was being made not by his compatriots but by Franco’s Moorish troops, who were enthusiastically slaughtering Spanish workers, just as they had been doing since the beginning of Spain’s disastrous colonial adventure in North Africa.

“Letter to Spain” was his sophist response to this epic failure of solidarity between the oppressed:

Letter from Spain

Addressed to Alabama

Lincoln Battalion

International Brigades

November Something, 1937

Dear Brother at home:

We captured a wounded Moor today.

He was just as dark as me.

I said, Boy, what you been doin' here

Fightin' against the free?

He answered something in a language

I couldn't understand

But somebody told me he was sayin'

They nabbed him in his land

And made him join the fascist army

And come across to Spain

And he said he had a feelin'

He'd never get back home again.

He said he had a feelin'

This whole thing wasn't right.

He said he didn't know

The folks he had to fight.

And as he lay there dying

In a village we had taken,

I looked across to Africa

And seed foundations shakin'.

Cause if a free Spain wins this war,

The colonies, too, are free - -

Then something wonderful'll happen

To them Moors as dark as me.

I said, I guess that's why old England

And I reckon Italy, too,

Is afraid to let a workers' Spain

Be too good to me and you - -

Cause they got slaves in Africa - -

And they don't want ‘em to be free.

Listen, Moorish prisoner, hell!

Here, shake hands with me!

I knelt down there beside him,

And I took his hand - -

But the wounded Moor was dyin'

And he didn't understand.

Salud,

Johnny

Uncharacteristically, Hughes omits to mention in this beguiling portrait of fading/false consciousness that the Popular Front had also opposed the decolonisation of Morocco, apparently in order to avoid upsetting their French counterparts; and that while the communists might have believed that despite this they still retained some moral right to assistance from the Moors, Franco at least paid and fed them before sending them off to tangle with forces dedicated inter alia to rooting out their religion.

So where did the Hughes/Stalin gig go from here? I didn’t read enough this morning to find out, although I’m impressed by the success of his post-1939 insistence on “I know nothing!”–check him eg at the McCarthy hearings. “Dear Mr President” suggests that he was to say the least ambiguous re black American participation in WWII, marking a split that had already emerged between him and educated members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade–they had resented his grouping them with country bumpkins at home and abroad on the basis of skin pigment, and who served in the European war, apparently putting national salvation before proletarian and/or racial internationalism.

Similar posts

- Berlusconi and the new (Roman) falange

Mr Clarke blogging at It’s Probably The Pox, My Son links to a typical bit of mendacity, or gross ignorance if - Catalan language policy: Marxist, Stalinist, Francoist or fascist?

The precedents for, and some possible implications of, the Catalanisation of Barcelona’s cinemas. Plus some crowd-pleasing video of the Quebec language - El Barça, Franco’s favourite team?

There is no statistical evidence for claims that the Franco government worked for Real Madrid and against Barça. - Casanova warns Spanish authorities re sexual mores of “Swiss” immigrants to Sierra Morena, plus the etymology and origins of flamenco, and other items of interest

One of the many etymologies of flamenco is rather curious. From the typically poor Spanish-language entry in Wikipedia: Durante el siglo - German multinationals

In May I posted a Dutch translation (1, 2) of an article by Vic prof, Manuel Llanas, describing the influence of

How about Wikipedia: