The Barcelona region contained a quite extraordinary wealth of weird medieval religious art until Napoleonic and Marxist visionaries decided to clear the decks to make way for their curious vision of earthly Paradise. One of my favourite survivors is the so-called Santa Majestad/Santa Majestat statue in the parish church of Santa María in Caldes de Montbui/Caldas de Monbuy, famous since Roman times for its 74ºC hot springs:

it rises much hotter than either the spring near Aix la Chapelle, or those of Bath or Bristol; it is boiling hot, and the people of the town come constantly there to boil their eggs, cabbage, and all sorts of vegetables, by simply suspending them under the spout of the fountain in a basket, and yet make use of no other water, when sufficiently cooled, for drinking either alone, mixed with wine, or cooled with snow [!!!] in orgeats, sherbets, &c. (William Gregory, British consul in Barcelona, in John Talbot Dillon, Travels through Spain (1781))

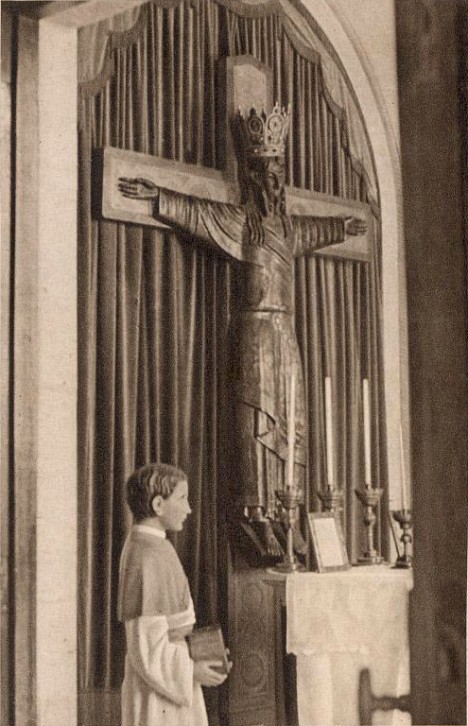

I say so-called, because, unusually, the image combines Christ in Majesty/Glory, the customary representation in Anglo-Cabronia and other less confusing lands, with his martyrdom. Only the head survived the Civil War, but here’s a stereoscopic image by Josep Salvany i Blanch of the original, and here’s a photo of the post-war reconstruction:

That’s clearly not a conventional Christ the King or Killed. The November 2 1907 edition of the Barcelona journal, Orbi…! curiosidades científicas, arte e historia, inventos modernos, actualidades, explains why:

The Roman town was born around that liquid pyre, and its inhabitants, the Aquicaldenses, soon erected, between their dwellings and public swimming pools, beautiful temples dedicated to Apollo, to Minerva and to the Goddess of Health, whose votive stones are now embedded in the wall of the Catholic temple, where is venerated the Rex tremendous majestatis.

This Byzantine beautiful sculpture, eyes wide open, head raised, beard parted and with ringlets, inspires a certain terror. Its long tunic, strewn with colourful drawings, with hippogriffs, eagle-headed lions and other mythological animals, recalls the Majesties of Luca and Berilo Siriana [who?!], amidst mists of Indian deities. The imperial crown, with the breast band adorned with seven stars and the hanging waist belt gives to the Majesty of Caldas an sense of grandeur and severity…

The beautiful tradition that His Holy Majesty was carried to Caldas by a caravan of Bohemians and deposited in the church as proof of their Catholicism and as safe passage in their travels across Spain, has been replaced by the vulgar version that the beautiful image served the Bohemians as a bridge with which to ford rivers and streams.

Wikipedia says the image was brought by the gypsies in the mid-15th century (they entered Barcelona on June 11 1447, Enciclopèdia Catalana claims it’s early 13th century, while something calling itself Europa Románica believes it’s 11th century. If it was brought by the gypsies–I assume they constructed it shortly before–it would form part of a pattern of gypsies impersonating wandering Christians in order to justify campaigns of organised begging during their great migration west in the 15th century. Here’s an edited-down version of Stephanie Folse‘s best-guess summary of how and why gypsies ended up in Europe (much more detail at Rombase):

Three migrations from the mouth of the Indus, driven by barbarian invasions, gave rise to the Domari in Egypt and the Middle East, the Lomavren of Armenia and eastern Turkey, and the European Romany.

A 1068 Life of St. George tells of a recent plague of wild animals afflicting an imperial park in Constantinople. The Emperor called on “a Samaritan people, descendants of Simon the Magician, who were called Adsincani, and notorious for soothsaying and sorcery,” who killed the beasts with charmed pieces of meat. By the 1300s large numbers lived a shanty settlement known as Little Egypt outside the port of Modon/Methoni, halfway along the pilgrimage route between Venice and Jaffa.

Leonardo di Niccolo Frescobaldi thought they were repentant sinners, and during the 15th century, catching on to this need, they began to move purposefully through Western Europe, “claiming to be pilgrims and demanding subsidies and letters of dispensation.” They told the same tales and used similar supporting documentation (cf “Tengo 4 ijos”).

“The usual scam involved a group claiming to be from Egypt or Little Egypt … showing up in a city and informing city officials that they were Christians doomed to wander for a period of years to fulfill a penance imposed upon them for the sin of neglecting their religion. They would collect food, money and letters of protection from the city and then continue to the next town.

“By 1417, Gypsies were recorded in Germanic cities. In 1418, several thousand Gypsies under a leader called Count Michael showed up in Strassbourg. Gypsies were entering Brussels and Holland by 1420, Bologna in 1422, and showing up in Rome in July of that same year. They travelled into Spain by 1425 and Paris by 1427.

“By the middle of the century, rulers and town governments started banning Gypsies, usually citing theft, fortunetelling, begging and sometimes espionage as the reasons. Europeans also recognized as lies the Gypsies’ claims to be pilgrims in exile from Egypt, but there are a few instances of alms being given into the sixteenth century, apparently by slow learners.”

Anyone got more stories of gypsies bearing virgins or emperors, particularly to Montserrat?

Flotsam: this Provençal carol has gypsies from the east providing post-natal forecasting services at the birth of the Saviour, a smart and creative reinterpretation of the Magi myth; the brilliant Jesuit, Lorenzo Hervás, quite unfairly maligned by rival-cult member George Borrow, in his Catálogo de las lenguas de las naciones conocidas quotes descriptions from a variety of sources of the arrival of the gypsies in Europe, and their mixing with Moors and Hispanics in Spain; Barcelona is of course home to a sizeable community of Sindhi refugees from modern mayhem, but as far as is known they haven’t yet got together with Barcelona’s gypsies to talk about life on the Indus before Genghis and Tamerlane.

Original

Alrededor de aquella pira liquida nació la villa romana, y sus habitantes, los Aquicaldenses, elevaron pronto entre sus moradas y piscinas públicas, hermosos templos dedicados á Apolo, á Minerva y á la diosa de la Salud, cuyas lápidas votativas quedan hoy empotradas en la pared del templo católico, donde se venera el Rex tremenda majestatis.

Esta hermosa escultura bizantina, con ojos abiertos, cabeza levantada, barba partida y buclada, inspira cierto terror. Su larga túnica, sembrada de dibujos coloridos, con hipógrifos, leones con cabeza de águila y otros animales mitológicos, recuerda las Majestades de Luca y Berilo Siriana, entre las brumas de las deidades indicas. La corona imperial, con la banda pectoral adornada con siete estrellas y el ceñidor colgante, dan á la Santa Majestad caldense una impresión de grandeza y severidad que el antiguo cicerone derrumbaba con su helada narración, que á fuerza de ser repetida, había dado nacimiento á una inaguantable brutalidad.

La hermosa tradición de que la Santa Majestad fué llevada á Caldas por una caravana de bohemios y depositada en la iglesia como prueba de su catolicismo y pase seguro en sus correrías por España, ha sido substituída por la vulgar narración de que la bella imagen servía á los bohemios de pasera ó puente para vadear arroyos y torrentes.

Similar posts

- More iconoclasm in the Catalan pre-Pyrenees

Re yesterday’s post on the Santa Majestat in Caldes de Montbui, here’s some anti-Catholic propaganda from the time of George Borrow, - Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo on George Borrow

In between pints of Summer Lightning I’ve been reading bits of Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo’s account of heresy in Spain, Historia de - Langston Hughes in Spain

Idealism vs realism as a Stalinist hack copes with the Italian bombing of Barcelona but struggles to explain why Moorish peasants - Gypsies & Sindhis & Catalonia

Hordes of otherwise quite sensible people here spend acres of time (makes sense to me) worrying about whether their sacred language - Gypsy madonna, madonna gypsy

Who’s copying

Another early gipsy scam was to pretend to be a lost legion of Romans, hence the name Roma, I think. I wonder whether they brought their metal working skills from the sub continent, or whether tinkering was another useful meme they learnt en route. There was precedent for people with such transferable skills taking their place in European society. For example, I read your posts on stags arriving from the East and wondered if you knew that the silver on the Gundestrup cauldron was obtained from Romania (there was no silver source nearer) and that the deer motif on it is Indian, not Celtic as the hippies like to think.

I’d say it was a safe bet that the Gundestrup Cauldron came from Gundestrup. Personally I’d asscoiate it with the Cimbri, given the fact they came from that area and had celtic names, and the figure is clearly the Celtic god Cerunnos.

Romanians are very fond of “Columbus was Romanian !!!!!!1111!!!!!” theories.

I thought it was generally agreed to have been of Thracian manufacture (so adjacent to modern Romania) using SE European or Eastern motifs, so I suppose you could speculate (as Timothy Taylor) did that the makers might have been a kind of proto-gypsy class of itinerant Indian metalworkers.

(It would however constitute more than a grammatical error to say that the word “Celtic” covers a multitude of Sindhs.)

Thanks for that, Attila the Pun.

The cauldron does use certain SE European motifs, but the famous image of the torq wearing horned man is pretty clearly Cerunnos.

It could be a commision, a copy, the work of a slave from that region or evdence of an unrecorded indigenous tradition. I’d still say the Cimbri connection is the most logical.