Some of the recent obituaries of super-poet Willem Wilmink (1936-2003) managed to avoid mentioning his writings in Twents, despite the fact that this part of his work – he also translated, wrote and rewrote extensively in Dutch – enjoyed a large following in Twente.

Some of the recent obituaries of super-poet Willem Wilmink (1936-2003) managed to avoid mentioning his writings in Twents, despite the fact that this part of his work – he also translated, wrote and rewrote extensively in Dutch – enjoyed a large following in Twente.

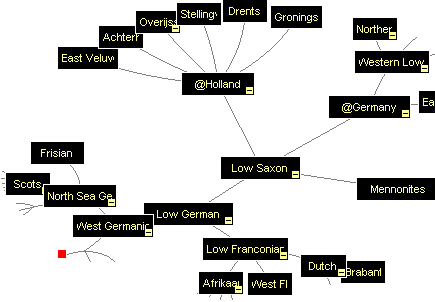

Let’s start by locating the two languages. Linguists classify Dutch and Twents respectively as Low Franconian and Low Saxon variants. Click the following diagram and you will encounter a gorgeous applet that will help you understand what that means in practical terms. (Double-clicking most nodes will provide background info in text form.)

There’s a certain amount of truth in all this, but the traditionally decentralised nature of northern German society means that there are no simple language barriers out there, and that there are as many classifications as there are classifiers. Put simply, many speakers of Low Saxon and Low Franconian dialects would have viewed the development of worthy institutions like l’Académie française as a less useful way of expending their time and energy than getting drunk and laid in their own or – preferably – someone else’s village. And stuff like that. And when they finally made it home, they described their experiences in rhymes, songs and stories in which the problematic relationship between lust and genetics in swamp villages and isolated forest settlements is never far from the surface.

I think that the strength of popular literary expression in northern Europe is an important reason why industrialisation, urbanisation and the growth of the modern state led to less cultural greyout in Holland and northern Germany than in France and Spain. However, the concentration of work and leisure in towns as opposed to inaccessible villages did give rise to important changes. In Holland, for example, a conglomerate of Friesian and Dutch grammar and vocabulary arose which people called Stadsfries – urban Friesian. A similar development occurred in Twente and when Goaitsen van der Vliet, an orderly Friesian with a fondness for spelling rules, published Willem Wilmink’s 1992 collection of poetry, Heftan Tattat!, it was subtitled Poems in Urban Dialect.

Now, there is no doubt that there exists a semi-standard urban Twents, formed in a similar fashion to Stadsfries, and spoken by young people in bars, factories and offices. However, unlike Catalans, poets in Twente don’t generally write poetry in order to drive home politicolinguistic points. As van der Vliet subsequently wryly acknowledged, Wilmink wasn’t writing so much in a standardised Stadstwents as in one of the many ephemeral dialects that sprang up in the twentieth century from the combination in Twente’s textile and metalworking districts of dialects from up, down and across the border:

This little book is written in the Enschede dialect. To be exact, it is Kupersdieks, because they don’t talk the same town dialect everywhere. In Pathmos, for example, it’s much more Drents. Kupersdieks was spoken more or less round the Kupersdiek [Kuipersdijk] and the Javastroat [Javastraat], the neighbourhood where Willem Wilmink grew up in the years 1936-1954.

I’m sure Wilmink didn’t see it in these terms, but in some ways Heftan Tattat! constitutes a tribute to the vibrancy of popular writing amongst this particular bunch of Low Saxons. Here’s a classic Enschede poem from the collection, followed by my translation:

Eanske

Eanske is onmeunig mooi.

Eanske is onmeunig mooi.

‘Joa, oons oalde Eanske,’ zeg mien moo,

‘is hoast net zoo mooi as Almelo:

Eanske is onmeunig mooi.’

Warsall

Warsall is a luvverly towun.

Warsall is a luvverly towun.

‘Warsall, my son,’ said my old mum,

‘is almost as luvverly as bits of Brum:

Warsall is a luvverly towun.’

Similar posts

- How to write an intermezzo in the style of Willem Wilmink

With translations of “Een jongen krijgt een meisjesbrief” and “Bacteriën”. - Galdós and those spud-crazy guiris

Where did he get that - Reisje langs het Rutbeek

Enschede a/ zee heeft een reisbedrijf ontdekt, Kasbah.com, dat strandvakanties in Enschede verkoopt. De wateroverlast was behoorlijk toen de gletsjers zo’n - Iberian debut of a classic paranoiac Dutch neither-nor motif?

You do something bad, I’ll do something - Chistabín

Currently doing a bit of literary translation out of one very strange dialect into another, and here’s something not so completely

Tot zulken grootheid zal Amstelredam nog komen,

Dat zij in treff’lijkheid zal overwinnen Romen,

In deftigheid van Raad, in Mannelijk Geweld,

In Orelogs-beleid, in Machtigheid van geld,

Dat haar geblazen Faam zal snorren door de wolken,

En dreigen met ontzag de wijdgelegen volken,

De Geel en Zwarte-Moor, de Turk en Perziaan,

Die zal haar mogendheid om hulpe smeken aan,

En onderhandeling met haar als vrienden plegen

Met Wissel of met Waar, na dat ‘t komt gelegen,

En doen gelijkelijk afbreuk en wederstand

Den Spaangiaard, vijand van ons waardig Vaderland,

Al door ‘t bestieren van Godes voorzienigheden,

En ‘t herelijk beleid der Staten onzer Steden.

‘t Kan verkeren.

Hoezo, geen politicolinguistic points?

Never trusted those bloody coastal Franks myself, although it must be said that 90% of his other work centres on the phrase Cupido klein den braven schutter. Did someone read the troops some Bredero before they got on the plane to Baghdad?

Willem har meesttieds nen leedke in n kop as e nen verske maakn.

Biej dit verske was dat ‘London is the place for me’.

Kun iej oen verske doar ok op zingn?

Joa, as wie doar ne calypso van maakn, net as Lord Kitchener, moar ik kan mie hoaste nich veurstell’n dat Wilmink zienen teks hierbiej zingn kon:

London is the place for me.

London, this lovely city.

You can go to France or America,

India, Asia or Africa,

But you must come back to London city.

Well, believe me as I am speaking broadmindedly,

I am glad that I know my mother country,

I’ve been travelling to countries years ago,

But this is the place I want to see

London is the place for me.

To live in London you’re really comfortable,

Because the English people are very sociable.

They take you here, and take you there,

And they make you feel like a millionaire.

London, that’s the place for me.

Somebody who seems to have no name wrote here: “I’m sure Wilmink didn’t see it in these terms.”

Being the one who actually wrote the article “Oaver t plat, de stad en nog zoowat” I know that the cited words came straight from Willem’s mouth. Besides that: he authorised each word.

Being the publisher of Heftan tattat! I also know that the language used has nothing to do with the current urban language of Enschede. The term ‘stadsplat’ was especially used in order to justify impurities in the Twents language the poems were written in.

By the way, it is a language that largely complies with the “Klank- en Vormleer van het Dialect der Gemeente Enschede” (1938) by Herman Bezoen. You can call it every name you want, even “Kupersdieks”, although the language used in Heftan tattat was never spoken in the Kupersdiek in Enschede. It only exists in the book. I know that for a fact. I could explain all this, but I do not now.

Goaitsen van der Vliet

Couple of apologies:

1) I’ll correct the template so that my name appears at the bottom of each post.

2) “I’m sure Wilmink didn’t see it in these terms” was actually intended to refer to the following clause, not the preceding quote.

3) I’m aware of the difference between what is here termed stadsplat and current urban Twents and am sorry if my chaotic prose seemed to imply that the two were somehow one and the same. (On the other hand, if there weren’t at least a fleeting resemblance, Wilmink surely wouldn’t be as popular as he is and you, as one of his publishers, wouldn’t this morning be sipping champagne on a 60m yacht in Monaco.)

4) Dude, I wouldn’t dream of calling it Kupersdieks or anything else without calling you first.