Charlie Hebdo’s First World War commemoration editorial boils down to “nasty to partake, nice to remember,” referring to the ease with which we now equate WWI soldiers of both sides, whereas “some discomfort would be the result if we were asked to shed a tear simultaneously for the Americans at Omaha Beach and for the Waffen-SS…” I’m probably about as un-collectivist as CH, but I surrendered to Remembrance Sunday years ago after seeing a woman weeping bitterly by the roadside in Clayton-le-Moors, Lancashire, as we of Darwen Town Band marched past, snow began to fall and, as if in a dream, an unattended telephone box began to ring. This year I’ve transcribed 50,000 words of my doctor-grandfather Trevor ApSimon’s war correspondence (1918-1932; 1915-7 to come), traditionally referred to by materials scientists as “the toilet-paper letters.” I thought that today of all days, Remembrance Sunday 100 years on, I would share some of what I’ve found.

A few years after the banding episode I read a couple of amusing realist novels by a turn-of-the-century Berliner called Georg Hermann.[1]My path to Hermann: getting mixed up with the creators of a Low Saxon drama about a 1930s textile strike (foundational lyrics); then, on those quiet mornings before music called, struggling through a Silesian predecessor play about hungry weavers in the 1840s, Gerhart Hauptmann’s De Waber; then Theodor Fontane’s Prussian portraits, which inspired Hermann. Serendipity brought me back to his work yesterday, and amongst his miscellaneous writings, in a 1937 meditation on four years spent in the Netherlands, there’s this:

The story is told of the English Reverend – not to be confused with revenant – whose ship suffered a small accident in the port of Piraeus which forced him to interrupt his journey for three days. When he got home, or, better still, in those three days, he wrote a three-volume standard work on Greece.

Hermann will be back at the end, but his cautionary tale is worth retaining in the meantime. For, however much I read, and though I know soldiers, time interposes a curtain between me and granddad, just as he curtained his “poor dear Ma” from the grisly nature of his battlefield work for the Royal Army Medical Corps (and hence reminders of the fate of another son, Arthur, killed at the Third Battle of Ypres), and just he was curtained by inexperience from a full understanding of this terrible new world.

- Granddad

- Gallipoli, Sinai and Palestine with the Cameronians & Royal Scots, 52nd (Lowland) Division

- Northern France vs the Middle East

- A tale of three ladies: 1918 and Armistice Day with 6th York & Lancs, 32nd Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division

- Waiting for demobilisation

- Post-war family and correspondence with a German who had also lost a brother

- World War II

- Later life

Granddad

Granddad, better known as (Thomas) Trevor ApSimon, was born in 1880 in Liverpool, the son of a North Welsh entrepreneur (whose father was a celebrated radical ranter) and of a New York Irish-Scots lady (one of 11 siblings, whose parents had repatriated to Merseyside). He and his three brothers were brought up in what you might call catholic nonconformism: his parents partook of Calvinistic Methodism,[2]Re Calvinistic Methodism – Welsh nationalism at prayer – I am driven to steal a marvellous anecdote, dug up by Michael Gilleland. From G.G. Coulton (1858-1947), Fourscore Years: An Autobiography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1943), p. 172 (on John Owen, 1854-1926):

Therefore, much as he loved his native tongue, he favoured no violent efforts to revive it. He had begun with his own family. For the first two or three children, he made a point of bringing nursemaids down who spoke the Cymric pure and undefiled of Snowdonia. This had one curious and unexpected reaction. His eldest boy was only four or five when, one fine summer day, Owen told me of a dialogue in the garden before breakfast. ‘It’s a fine morning, Father.’ ‘Yes, my boy.’ ‘Trees growing fine.’ ‘Yes, my boy.’ ‘Jesus Christ makes them grow.’ ‘Well … yes, my boy.’ ‘I know what he makes them grow for … He wants them to burn people with.’ The nursemaid from Snowdonia was, probably, a Calvinistic Methodist whose own rudimentary eschatology had been absorbed in a still cruder form by the child. Congregationalism and that strange bird, mainstream Presbyterianism, but were pious rather than fanatical. However, there was always a clear understanding of the disguises adopted by the Antichrist: alcohol, fornication, and frivolity.

Best-laid plans: granddad announced not long after signing the Pledge, a life-long renunciation of booze, that his signature had no moral force because he had been too young to know what he was missing; fornication will be back shortly; and it has to be said that granddad’s father, Thomas, hadn’t really taken the proscription of frivolity to heart: Thomas’ profligate spending, whilst bewitched by golden mirages, meant that it was half-uncle Old David, himself a GP, who paid for granddad’s medical studies at Liverpool University, in order that he might follow in David’s more prudent footsteps.

Gallipoli, Sinai and Palestine with the Cameronians & Royal Scots, 52nd (Lowland) Division

Typical RAMC/Royal Army Service Corps organisation in the latter part of the war. Image: BBC.

Typical RAMC/Royal Army Service Corps organisation in the latter part of the war. Image: BBC.

By May 1915, after some years in general practice, perhaps at Neston, Cheshire, he joined the RAMC as a Temporary Lieutenant. This was after the Second Battle of Ypres, at which the Germans, violating the Hague Convention, made first use of chlorine gas. My impression, the 1915-7 letters unread, is that he felt a patriotic duty to help avenge the outrages committed against his fellows in the course of German aggression. He went first with the 52nd (Lowland) Division to the Eastern Mediterranean, mending Royal Scots and Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) following encounters with German-led Ottomans, first at Gallipoli. Then, with the same regiments but now under the aegis of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, he was in Sinai and Palestine, working at the Battles of Romani, Gaza, Jerusalem and Jaffa. He also moonlighted in Welsh as a photojournalist (more some other time), and took many of the photos which, uncredited, illustrate Ralph Reakes Thompson’s 1923 history of the Division. They include what was considered a quite scandalous one of hairy-arsed Glaswegians bathing naked on Gaza beach, which I’ll post when I’ve scanned it. Here for the meanwhile is a long shot:

The 52nd was shipped to Northern France in April 1918 to try to halt the German Spring Offensive. After three months in and out of the front line on the Western Front, he was, to his considerable disgust, separated from them, and spent the Second Battle of the Somme running ambulance trains, before being transferred to the York & Lancaster Regiment for the latter part of the Hundred Days Offensive which, for him, brought the war to an end on the Franco-Belgian border. After the Armistice he worked until at least May 1919, now a full Captain, in base hospitals with Allied and German invalids.

Northern France vs the Middle East

On the change of scene (14/05/1918):

I look back with mixed feelings on the East. The bright sun there is cheering & luxurious; and there was always the novelty of a very strange land. One picks up something of the happy-go-lucky fatalism of the East; besides the war was younger and in the Sinai campaign so were our men. Marching through the desert in the clean drill clothing with sun-bronzed faces they looked graceful & handsome. But the best of them are dead, especially the keen youngsters; and after the fighting in Palestine, as the sergeant major said to me, they all looked older; there is hardly a boyish face among them. And here in dull serge clothing, muddy boots & tin hats, instead of shorts, shirts with the sleeves cut away, & sun helmets, & with no sun to brighten them, they are not half so cheering to the eye.

To be sure, many of them would as soon be here, even those who have been before; they have chance of home leave & marching in the heat was terrible out there. So far, that is, for they don’t know what may come. Consequently, especially amongst the officers who do not live so much from day to day as the men, the battalion is in sober mood. But the men do not let that distract from their enjoyment of civilisation again. We did not see Alex[andria] nor Marseilles hardly on the way, so marching through a little dingy French town after so much desert & empty plains I was struck with the pleasure & interest a Hottentot would experience on seeing Scotland Road [Liverpool] for the first time. It seemed to remarkable to meet a house every few yards; a third-rate factory & common little houses seemed remarkable achievements of industry and building. Formerly I hated such towns because of their ugliness, now I realise that, if they are not as beautiful as the desert, they are beautiful enough & not so confoundedly inhuman – altogether pleasing to the eye. Just as I suppose anyone who comes through this wilderness of death in France will think it good enough just to be alive.

His medicine certainly changed on his return to Europe. While he no longer had to combat malaria, cholera, the typhus louse and other Turkish delights, Northern France had its own discreet charm: high rates of (lethal) wound infection due to mud polluted with faeces; gas which left the fortunate blind and vomiting, with laryngitis and bronchitis; and, although the Somme has more hiding places than the desert, shell- and machine-gun fire that was considerably more fierce and competent. It is said that in France he initiated the practice of preventing likely death from middle ear infections behind burst eardrums by cleaning the cavity with alcohol and then filling it with DIY concrete. Better deaf than dead, but not all was gloom and misery, and sometimes modern medicine was not required. Writing to his brother, Estyn Douglas ApSimon, on 21/05/1918, he describes attempts amid heavy shelling to rescue men from a direct hit on a deep dugout:

They dug the man out. The others escaped, but this man was dead, his face & neck blue from asphyxia. Blood had poured from his mouth & probably not his lungs – a quick death.

But then:

In the afternoon I was in the mess of a neighbouring unit, when a major rushed in, rather pale & said to the Medical Officer, “Doctor, I’ve got a touch of gas.” He gave himself a whisky & soda & described how he was walking along a trench; suddenly his nostrils caught something – he breathed it two or three times; his orderly too – suddenly they shouted together “Gas!” & put on their masks.

And had a drink.[3]There may have been a belief that alcohol could help against gas attacks, perhaps encouraged by authorities worried about morale if word got about that mustard gas was actually dangerous. Here’s Lance-Corporal RG Simmins of the 90th Winnipeg Rifles on a gas attack at the Battle of Hill 60 in May 1915 (Walter Wood, In the Line of Battle: Soldiers’ Stories of the War (1916)):

While looking round in the cheerless dawn one or two of our sentries saw a yellowish kind of cloud coming towards us, over the hogback, and travelling pretty fast. The sight was unusual enough to be noticed, but no one who saw it had the slightest idea what it really was, until we were enveloped in the filthy folds; then we knew that it was poison-gas… I saw the yellow cloud come, I watched it as it enveloped us, and I observed it as it rolled away behind us and went towards Ypres, gradually losing force as it was absorbed in the air. In addition to being so favourably situated, we had just had a rum ration—and plenty of it. I do not know whether the spirit did us any good, but it certainly did not do us the least harm, and may have helped to nullify the effects of the poison-gas.

A tale of three ladies: 1918 and Armistice Day with 6th York & Lancs, 32nd Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division

You might describe granddad’s life in 1918 as a tale of three ladies. First, there was his mother Annie, to whom most of the letters were addressed, many dealing with her chronic hypertension.

Second, there was Kandy, a Maltese terrier and literary device, sub-plot and running gag which diverted some of his mum’s attention from human destiny. Purchased as a puppy in Templar Valletta at New Year 1918, “an amusing little beast, the size of a kitten, white with black markings,” and named after troopship the SS Kandy (02/01/1918), she survived Palestinian sheepdogs, jackals and reptiles and the German Templers (yes) of Sarona, shelling and the prohibition of dogs on ambulance trains, and attempted poisoning with prussic acid by her master during an illness, to become the property of French railway engineers encountered at Péronne after the Battle of Mont Saint-Quentin: “She will always get on, as everyone takes to her, & that district is an excellent one for a dog. To bring her home would have meant a long quarantine – a rotten thing…” (02/10/1918). Unfortunately even the 52nd’s official history contains no photo.

Third, the lady he met on Armistice Day, and you will need to bear with me a bit here.

During the war he smoked at least ten full-fat Kenilworths a day, and, on the basis of his smoking in his mid-90s, I’d wager that those cigarette supplies from home were not his only source. And I think he may have assimilated the saucy Kenilworth advertising of the war years:

Kenilworths, check. Terrier, check. But now he was 38, and the immense joy he expressed to brother Estyn on the birth of the latter’s third in October 1918 was tempered by the sensation that the war had deprived him of an “adventure [which] I have always thought to be one of the greatest things”: a woman (and family) with whom to share his life (29/10/1918). The dystopia in which he felt himself trapped had him reaching for similes to the masterpiece of English nonconformist allegory, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s progress.[4]Ancient & modern mingle elsewhere. On 01/11/1918 he writes: “The bombardment was a continuous rumble & I lay awake for a time listening to it & thinking what very thunderous tones Democracy now adopts towards the ancient relics of a Europe which is passing. It was like the rumble of innumerable waggons down stone flagged roads.” Here at more length is a diary entry for the afternoon of what was, unbeknown to him, one of the last days of the war – probably the 8th. He is with 6th Battalion York & Lancaster:[5]The regiment was recruited mainly in the West Riding of Yorkshire (the Lancastrian reference is historical). Granddad spent part of his youth at Sowerby Bridge outside Halifax. It is said that the regimental museum and archive in Rotherham is very good.

We moved out of Roisin at 11.20 past a big mine crater, where a couple of mules & a limber, having walked into it, had spent the night up to their necks in water. When we got on to the road to Meaurain the Boche artillery woke up & shells began to fall all around. I judged it wisest to march on to get some cover in the village at the entrance to which there was 50 yards of sunken road. We just got to it in time, shell after shell bursting behind us & falling also on the far side of the road. As we passed between a house & the church a shell came through the roof of the house & struck the church & a shower of bricks came down onto my tin hat. We hurried across the little square into a large estaminet, a shell bursting in the middle of the square just as we got inside. I was struck by the coolness of one or two of the men, especially one, Ramsden. Then there was a ridiculous little bit of byplay as to who should go down last into the cellar & we got good cover till the shelling stopped. Then we went on & I got the men into a cellar & my corporal & I reconnoitred the village to find a safe aid post but could find no suitable place. The civilians were in a state of panic – a shell had gone through into a cellar & killed some of them. I saw one white-haired old lady lying very still on a stretcher at the aid post of another battalion. The funny thing about French country people is that when there is any danger about, they seem mainly consumed by a desire to save their furniture & you see them running about with it. But it was pitiful to see frightened children & women crying & I have not much patience with people who want the war carried into Germany & do not realise that it would mean that kind of thing all through Belgium, to say nothing of exposing our men to enemy shellfire as they advanced. Civilians were mixed up with our advance all the time; the intelligence officer met the Mayor of Gussignies in the front line – he justified his presence because he was the Mayor.[6]A man who will know about local memories is Jacques-Antoine De Witte, lawyer at the Avesnes-sur-Helpe bar with offices at 19 Rue Nationale 59330 Hautmont, mayor of Gussignies in the 1980s, and occupant since 1978 of the local chateau. Apparently he has supplemented the recollections of his grandfather, Baron René De Witte, with archive research and oral history, and has given lectures on Gussignies during the First World War.

Paul Hindemith was serving on the German side in Gussignies on October 30th and November 3rd when he completed respectively the second and third movements of his Sonata in D for Piano and Violin, op. 11 no. 2. I don’t know how hellish it is. Very old women seem curiously indifferent to shellfire.I was starting lunch at 3.30 – we had gone into an empty house – when we got orders to move. I hustled my men, but they were slow & I found to my annoyance that the battalion had moved off, which meant I should have to guide my party by map & compass. Stragglers coming back gassed helped us & we got on the road, observing heavy shellfire ahead. We came to a turning across an open plan to the left and the shells began to fall nearer to us. One big High Explosive burst about a hundred yards in front, so we halted & took cover in a sunken road. We decided to go back to a house we had just passed as they might have a cellar; they had, but it was full up. One of the battalion runners, wounded in the hand, came back & I asked him the way, just to confirm my idea of it. He replied that the battalion was a mile ahead, sheltering in a sunken road, as the village we were going to was under heavy fire. That decided us not to hurry. The runner offered to go back & guide us to the battalion, an offer which I refused. That is an example of the spirit which animates so many of the men; the road ahead was all a-flicker with shellfire & this lad, on his way out of it all, offers quite unnecessarily to go back & show me the way.

We waited a bit & the shelling quieted down, so we hurried across the plain & joined the battalion. After a short halt we started to march down into the village & presently heavy shellfire began again. The village of Gussignies is in a deep hollow; it was fairly dark & seemed full of gas & the smoke of bursting shells; we went in amidst a perfect inferno of the blaze & crash of heavy shells; only one image that I have ever heard of could describe it; it reminded me irresistibly of Bunyan’s Valley of the Shadow of Death. Yet we had only one man wounded, I suppose owing to the road being somewhat sunken; soon, to the relief of everybody, we were all crowded into the cellars of a farmhouse, listening to the shells crashing into houses round about. We were not very happy – we were now the front-line battalion, having come up from support; the enemy line was near & next morning our men must turn him out. (16/11/1918)

The obstacle to this Pilgrim’s Progress is taken from Psalm 23, which everyone knows from “The Lord is my shepherd.” “Christian must needs go through it, because the way to the Celestial City lay through the midst of it,” and Christian proceeds despite warnings:

About the midst of this valley, I perceived the mouth of hell to be, and it stood also hard by the wayside. Now, thought Christian, what shall I do? And ever and anon the flame and smoke would come out in such abundance, with sparks and hideous noises, … that he was forced to put up his sword, and betake himself to another weapon called All-prayer. So he cried in my hearing, ‘O Lord, I beseech thee, deliver my soul!’ Thus he went on a great while, yet still the flames would be reaching towards him. Also he heard doleful voices, and rushings to and fro, so that sometimes he thought he should be torn in pieces, or trodden down like mire in the streets.

If we take the Celestial City to be Mons, icon of the British Expeditionary Force’s dreadful retreat in August 1914, then Trevor didn’t reach it by Christian perseverance. Instead, the Germans – or some Germans – lost the will to fight. On 02/11/1918 he noticed the first signs of the German Revolution – “The Boche airmen are throwing down leaflets saying they have a democratic government now & want peace” – and as they marched into Belgium at Goegnies-Chaussée on the 10th, there were “great rumours.” On the 11th he wrote his first undated letter of the war:

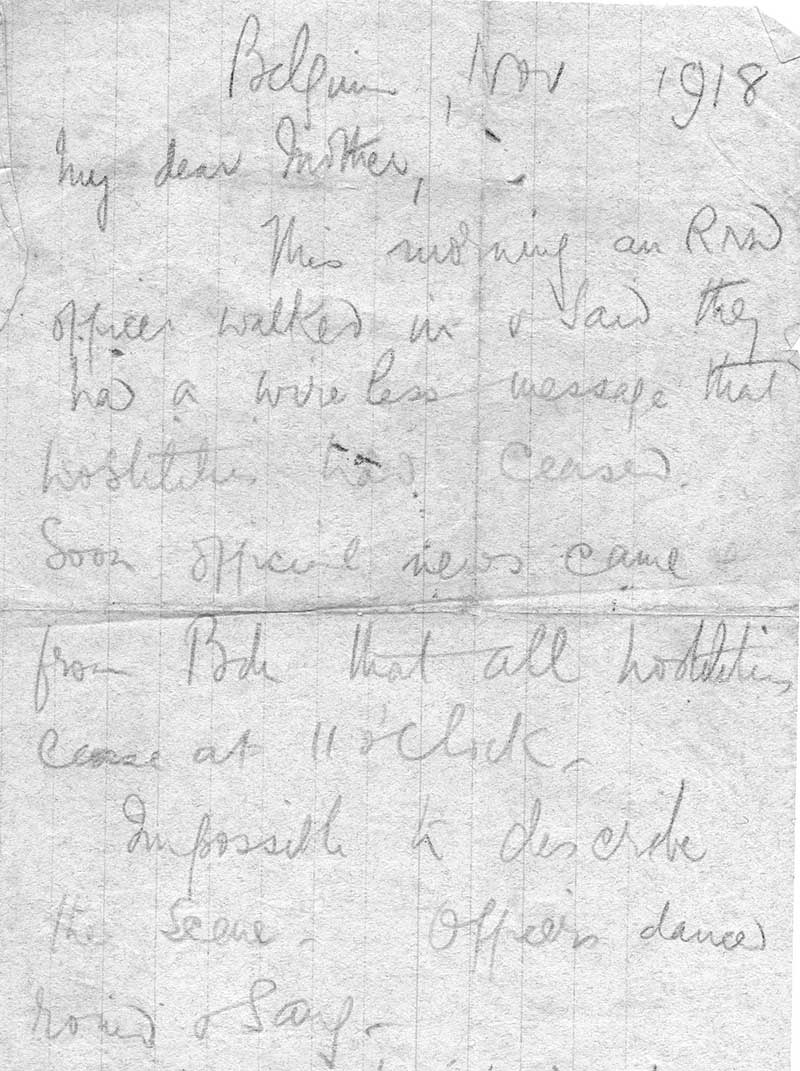

My dear Mother,

This morning a Royal Naval Division [?] officer walked in & said they had a wireless message that hostilities had ceased. Soon official news came from Brigade that all hostilities cease at 11 o’clock.

Impossible to describe the scene. Officers danced round & sang.

There will of course be great rejoicings, but there are a million British dead. Many out here have lost brothers & their rejoicings are of a very sober character. I felt in the early days of the war that, though the chance of one of us getting through were good, it was not likely that both would, & of course Arthur’s risks were much greater than mine. “One shall be taken & the other left” [Matthew 24:40]. But as he said [Arthur wrote a tender, brave testament on the eve of Ypres III, knowing and accepting his fate], no loftier destiny could be his. His memory will be an inspiration to all who knew him.

Yr affec Son

Trevor

But there was unfinished business on Armistice Day: his third lady, at least for half an hour. My impression from various letters of that period and a map is that he found her in Mons or Valenciennes. AMA reports a conversation with him in the 1970s:

On the day the war ended, when the ceasefire began, I have a feeling that he was somewhere on the Belgian fronter, possibly near Mons. I think he felt that he had been short-changed in the matter of pleasures in the wartime, so he called on this French, what would you call her, madame, I think the lady was her own master. Unfortunately he discovered that he was unable to perform, but the lady was not at all distressed and treated him to a brandy. I think he rather thought that he had got through the war successfully and that virginity was an overrated virtue.

Waiting for demobilisation

Two months followed at Haveluy, just back across the border into France, caring for his Pontefract men and accumulating a civilian practice dominated by Spanish flu (there’s a message from 1918 for you: “Get yer flu jab!”) and by drawing “animals and funny men” for small boys (18/12/1918). Then via a Paris (full of prostitutes and thin-faced, bespectacled Americans “who move along with an intensely hopeful, don’t care a damn for you, kind of expression” (22/01/1919)) to his next posting at No. 10 General Hospital on the Bruyères racecourse at Rouen. There he sat in mess between two quartermasters:

They are always of the old soldier type, these quartermasters. They have rows of medal ribbons – Boer War, China, Long Service, Good Conduct etc. They feed terrifically, have great liquor-holding capacity – an essential quality for survival in the Regular Army, where a man must have been able to drink without getting drunk – tend to run to fat especially round the chin, measure 46-48 inches round the chest & Heaven only knows what round the waist. They are very capable, practical men, who know a great deal about things; about clothing & rations & generals & wines & cigars & India & how to deal with natives; they have a reputation for being on the make & have generally a tidy sum put by. (01/02/1919)

He was less enthusiastic about the seven wards of Germans in his care:

The last lot in have just come down the line & are in rather a badly-neglected state… These Germans are mostly socialist – against the Kaiser – & won’t admit that they have been beaten in the field. There is one who always amuses me – when I go in the ward he yells out “Arthug” or some such word – probably it means “Attention.” As a rule nobody is fit to stand to attention, but that doesn’t worry him, & when I go out he yells “Ahtung” (? stand at ease). He is an amusing relic of German militarism. (12/02/1919)

Thence to Rouen’s General Reinforcement Base Depot, and possibly with No 3 Stationary Hospital to Rotterdam. Whether he was demobilised in summer 1919 I don’t know, but his letters home ended on September 4th, 1919, when he described to his mother a day spent visiting the field of the Third Battle of Ypres and his brother Arthur Tryweryn ApSimon’s grave at Bard Cottage Cemetery.[7]One of Trevor’s references was correspondence with Arthur’s CO, Wynn Wheldon, commencing 07/08/1917, three days after Arthur’s death:

A battalion in front of us had failed rather badly and as I only had about 80 men left I was forced to put in Arthur with his signallers and runners to help to hold the new front the Welsh Division had won. Arthur went and did the job – the Guards and ourselves were the only two divisions which won and kept all its objectives. He was relieved the next night, the relief going on under the most terrific bombardment, and he came through without a scratch. When things were much quieter, he and another officer, Lieut. G.E. Evans, went to look at their men in the new support line and one chance shell found them both, but Evans was very slightly hit. Arthur was badly hit in the back [no dogtag, so presumably the blast exited via his chest…]. He was brought into Headquarter – an old German dugout – and was immediately tended by the Doctor and placed to rest in my bunk. He was, I fear, in some pain the first hour, but the Doctor soon eased that and, though he did not sleep much, he was fairly comfortable throughout the night and was conscious. We dared not try and get him to Hospital in the night – after the rain the ground was a morass – but in the daylight we got him down to a comfortable dressing station where I believe he died the following day.

I do not think you can believe how very sorry we all are to lose him. For some of us he was precious as one of the few survivors of the old 14th – he was for all of us a most lovable man who never spoke or thought unkindly of others, and of whom no one could speak or think except with affection. He loathed this war and all its incidents – he loathed soldiering – but never faltered in doing his duty to the most minute particular. After he was hit, I heard one of his men say: “Mr. Apsimon never seemed to mind shell fire.” I knew he did mind it – we all do – but his serene and quiet courage left that impression on his men, and gave them confidence and that was a great achievement for a man so sensitive as he was.

I will miss him personally, more than any officer I have ever known – his quiet humour, gentle nature, and the sturdiness of his views were ever a comfort to me. He said as he left the dugout on the stretcher: “I am sorry to part company with you Major,” and I dared not say how sorry I was, too.

I hope that one day Wheldon’s diaries of 14th Battalion RWF will become available.

Post-war family and correspondence with a German who had also lost a brother

A compassionate deity would have looked after him for a while on his return to the Wirral. But father Thomas died of influenza on September 18th (ironically, the Armistice and demobilisation caused a sharp increase in deaths);[8]As a child I remember AMA burbling the pre-war song, “I had a little bird, / Its name was Enza, / I opened the window / And in flu Enza.” brother Estyn seems to have become a drunk, was sacked by his employers in 1920, and went from bad to life as a literary agent; brother Joe, who seems to have suffered from oxygen deficiency at birth and spent the war tending an allotment, died in 1925; and high blood pressure finally took his mother Annie at his home-surgery in Wallasey in 1928.

Several shafts of light pierced this gloom. One was his marriage in 1924 to the Swindon-Welsh chemist and pianist pictured at the beginning of this post. 20 years his junior, in 1927 – frabjous day! – she gave this 46-year-old chain-smoker and whisky drinker his first son, who was named for Arthur on the tenth anniversary of Passchendaele.

An equally improbable ray is this communication:

Berlin-Schöneberg

on the 20th of Januar 1926Dear Sir!

In the last week we get your kind letter, in which you offered us the deary of my late brother, Karl Sterry, which is, as you wrote, in your possession. My brother Karl was until Januar 1916 on the battlefields of Russia, when he returned for a half year to Berlin. At the end of June 1916 he leaved for the third time Germany in order to go to the battlefields of France where he, according to the reports of some soldiers, was killed on the 10th of July in 1916 in the Mametz Wood near Petit-Bazentin on the river Somme. We have never get nearer accounts concerning his death. In the near of this battlefield your brother must have found, as I suppose, the deary. Never my brother has been in Belgium, as you thought.

I think that it is for you without all doubt, that the deary of my dead brother is of the greatest interest for his mother, his sisters and his brothers. Therefore we pray you to send us the book, which you were so kindly to offer us.

With many thanks for your pains I remain with the greatest esteem

your

Wolfram SterryBerlin-Schöneberg

Stubenrauchstrasse 5a

Germany

How did the diary come to Wallasey? Brother Arthur was with 14th (Service) Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, 113th Infantry Brigade, 38th (Welsh) Infantry Division. At dawn on 10/07/1916, with the 13th and 16th on their right and left flanks, they advanced to Mametz Wood, destroyed the German front line with rifles and bayonets, and dug in. 113th Brigade itself suffered heavy losses and was withdrawn that night, so Arthur must have found the diary soon after the death of its author. He was a polyglot and a fine writer and judge of literature,[9]Arthur’s letters home seem mostly to have survived the censorship of military, mum and mice. They combine acute observation with classical elegance and subversive humour. One acolyte and perhaps lover, the bizarre New Zealand poet Walter D’Arcy Cresswell, was convinced that after the war this talent would have become as well-known as that of colleagues in the notoriously poetic Royal Welch Fusiliers (Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Hedd Wyn, David Jones, Frank Richards, Wyn Griffith, JC Dunn…), and dedicated what he regarded as his best work to Arthur (a homoerotic poem, Hylas) and to his memory (a ballad, The Voyage of the Hurunui). Cresswell prepared his archive of Arthur’s letters for publication, and it would be fascinating to talk to someone in Wellington able to access the manuscript of “The subjective soldier, being the letters of Lieut. AT ApSimon” in the Alexander Turnbull Library, part of the National Library of New Zealand. and it presumably drew his attention, amid the multitude of documents found on such occasions of carnage. (Robert Graves came up later with 2nd Battalion RWF: “We were in fighting kit and felt cold at night, so I went into the wood to find German overcoats to use as blankets. It was full of dead Prussian Guards Reserve, big men, and dead Royal Welch and South Wales Borderers of the New Army battalions, little men. Not a single tree in the wood remained unbroken” (Goodbye to all that, a comic-grotesque retelling of the conflict reminiscent of Arthur’s letters, and probably of those of many who survived more than a few months).)

The diary and several more letters passed between Wallasey and Berlin, and that was that. Except of course it wasn’t.

World War II

Trevor hoped at the time of the 1918 General Election (Labour? Conservative? Liberal, as ever, I believe) that

the Government, when elected, will soon disassociate themselves from the idea of making Germany pay the whole cost of the war. Some of these shrieking fanatics will create a “revanche” movement in Germany if they are not careful. I do not love the Hun any more than they but this is a time for long views & one does not want to see Dick [his infant nephew]’s generation in a war. (18/12/1918)

But there was Versailles; and anyway he had noted the refusal of German troops to even accept that they had been defeated; and then there was an Austrian, who also had a moustache and a small dog, but the dog was a pit bull called Fuchsl, “little fox,” not a terrier called Kandy; and so it came about that Dick – Richard – served in the Merchant Navy 1939-45.

When I transcribed Wolfram Sterry’s letters a couple of days ago, I casually googled his address, Stubenrauchstrasse 5a, Berlin-Schöneberg, and a name from the past (and from the beginning of this post) popped up: Georg Hermann, who also lived there for a while. Hermann was a Jew, and the article above, “Vier Jahre Holland,” written in 1937, was fruit of his having fled to the Netherlands in 1933, just before his work was burnt. Now I see that his Leitmotiv was the murky relationship between image and reality, and have found his splendid history of German caricature in the 19th century, whence this howling organ-grinder:

Of the couple of Hermann’s novels I read way back when, I particularly remember Rosenemil,[10]For some reason Rosenemil returns to me in Dutch, though I don’t think it has been translated. which opens with a debunk of the trees at the heart of German metropolitan identity:

In truth “the lindens” [of Unter den Linden] were by no means what one expected of them and what had made them the dream of every German patriot in every little town from the Elbe to the Vistula. As little then as now. For a century and more, people talked about them as if they were something of a miracle. They sang about them day and night, in Berlin letters and in caprices in the manner of Callot[11]I take this to be a reference to the genre, supposedly derived from the grotesques of Jacques Callot, invented in ETA Hoffmann’s Fantasiestücke, which I don’t know. and in hundreds of ditties from the Berlin farces. But the old, lowly houses here and there were, apart from a couple, really nothing special… And the funniest bit of all was that the trees weren’t even all lindens. There were horse chestnuts amongst them, as well as elms.

I think you know Georg Hermann’s fate, and by 1945 the trees on Unter den Linden were gone too:

Later life

Once a soldier, always a soldier. Granddad’s wartime experiences informed subsequent lobbying on clinical issues, but also, I suspect, his advocacy of a National Health Service, which led to accusations of communism in the BMJ. They also haunted him towards the end of his life, though when I was very young and he was very old he had by and large abandoned the whisky diet, and I remember finer things: blow-by-blow accounts of Oriental battles and a breathtaking escape on the last train from whatever; his trying to teach me to box (“One to the solar plexus to double him up and then an uppercut to the chin and PUNCH ME PROPERLY!”), because, as James Bond shows us, all of human society eventually comes down to two men fighting in a ditch; the extraordinary stash of sexual deviance and psychology in the greenhouse, his favoured spot for nude sunbathing and smoking; him blind and declaiming John Milton’s Paradise Lost – the epic verse at the heart of English religious and political nonconformism, “ancient liberty recovered to heroic poem from the troublesome and modern bondage of rhyming” – in a voice to make any singing organ-grinder proud, a voice that echoed at a funeral a couple of years ago in “Fear no more the heat o’ the sun” from Cymbeline.

Oh, and it’s official: the handwriting of doctors is no less legible than that of non-doctors.[12]Berwick, Donald M., and David E. Winickoff. “The truth about doctors’ handwriting: a prospective study.” Bmj 313, no. 7072 (1996): 1657-1658. So, another 120,000 words in Victorian scrawl coming up…

Anecnotes

Similar posts

- A Welsh story

The post-Napoleonic miseries in Llanuwchllyn and Bala (Merioneth), Liverpool, Sheffield, London and New York of the orphans of Thomas and Catherine - Sister Mary and the Bird

Translations from Welsh and Yiddish revealing ornithomancy amongst the 19th century north Welsh and Jewish Lithuanians. - In praise of oranges

A First World War letter from a Palestinian orange grove, an orange (lower case) song, and this winter’s favourite orange cake - Enric’s story

“I was 20 when I went to the - Transvestite barrel organ dancers in 1930s Whitechapel and the 1860s London West End

With acrobats, clowns, and Doris and Thisbe, goddesses of wind.

What a brilliant excavation of a life and through it, a time. Thank you for that. I only followed the trunk tonight ut I look forward to trying the branches soon.

You are far too kind, as usual. Looking forward to it!