AMA thought that the little history that follows was by (Thomas) Trevor ApSimon, while LAD credits TTA’s then long-dead father, Thomas ApSimon. Perhaps the tone and style are not those of TTA’s alert and cynical First World War letters but of a Sunday School reading (Thomas taught for twenty years at the Catharine St. Presbyterian Church, Liverpool) and of the sentimental Welsh-language WWI photojournalism that Thomas published under Trevor’s name, recounting the Sinai campaign and the taking of Jerusalem by Welsh Nonconformists at Christmas 1917. However, it was presumably Trevor who sent the piece to the Liverpool Daily Post, perhaps prompted by Woodham Smith’s The great hunger (1962), and he was more likely than his father to have read Petrarch.

[

Update – 1963 letter from NIA to JEA establishes TTA as author:

Glad you were interested in your Welsh ancestors. What a grim life! There are a few more letters which you can read – when you come as I hope you will – Trevor just wanted to make a brief sketch for their descendants to keep & thought perhaps there might be some antiques about the district who would remember the name. But I think his style is too telegraphic as though 6d a word & makes it hard to catch the imagination of the only faintly interested.

]

Much will become clearer, and the voracious public appetite for news of early 19th century north Welsh ranters and schismatics satisfied, when I publish translations of the speeches of Simon Jones of Bala; the autobiography of family friend and colourful lichen-gatherer, blacksmith and preacher Robert Thomas, better known by his bardic name Ap Vychan; and an extraordinary manuscript bundle recently received from New York, which appears to be the memoirs of Ap Vychan’s great friend, the blacksmith-poet Thomas Jones, one of the children of blacksmith-preacher Simon Jones of Lôn, Llanuwchllyn, to whom we now turn:

A WELSH STORY OF 150 YEARS AGO

BY THOMAS APSIMON

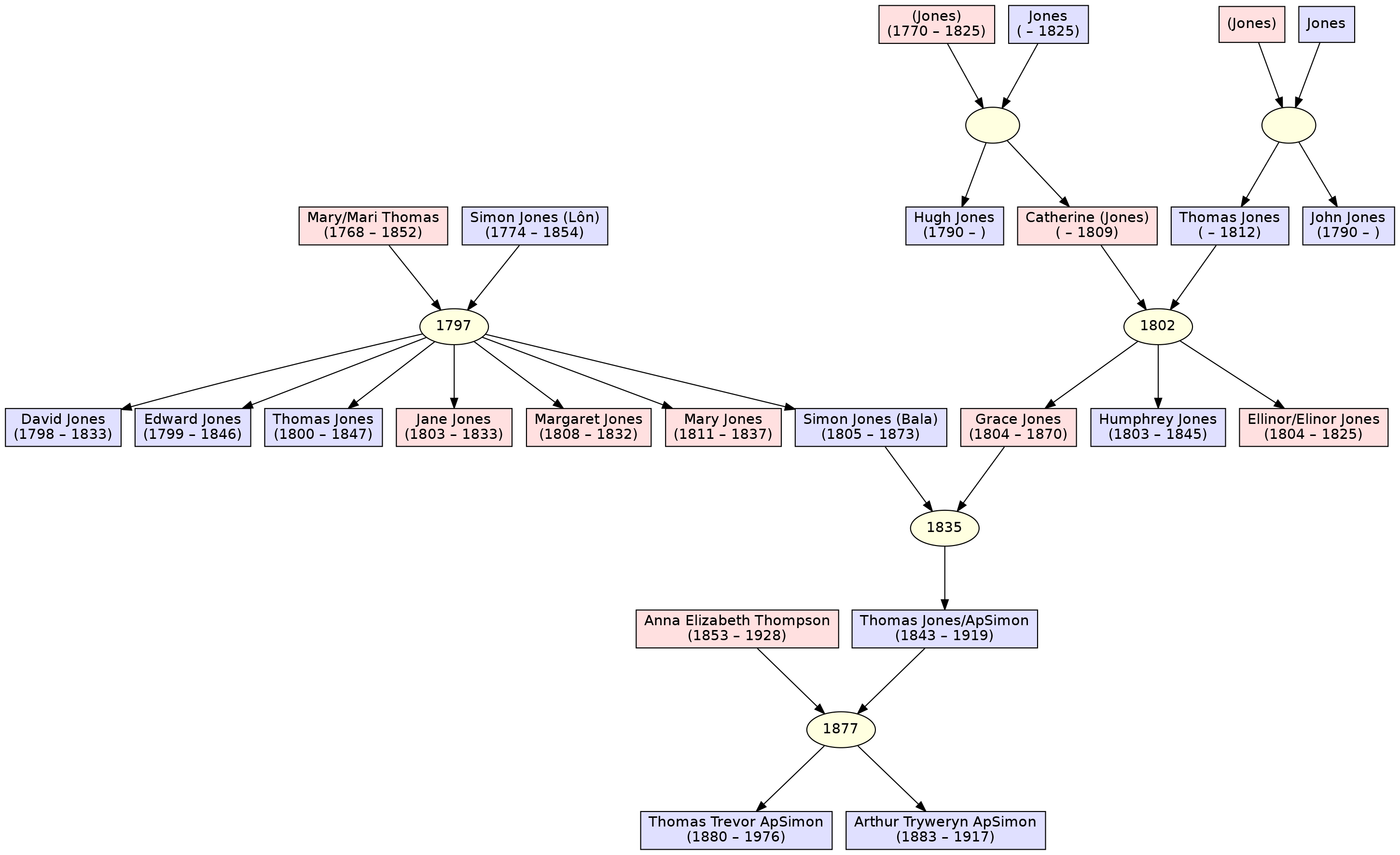

Liverpool Daily Post, Tuesday, March 2, 1965Simon Jones, blacksmith, and his wife Mary, of Llanuwchllyn, at the south end of Bala Lake, found it hard to rear their seven children, born between 1799 and 1812.

These were years of economic crises, a bad harvest in 1810, food scarcity, alternating inflation and deflation. The cost to Britain of subsidising her allies was staggering. So were rates and taxes, half of which were paid by the poor.

Time was to join this family with that of Thomas and Catherine Jones, who lived at Nantfach Farm twenty miles north of Bala in a beautiful and lonely valley, amidst gently rolling hills. Married in 1802, by January 1812 both were dead.

The view from the ridge above Nant Fach farm towards Cerrigydrudion. Image: Roger Brooks.Their children, Humphrey aged 8 and the twins Grace and Ellinor 7, thenceforth lived at Wergloddu Farm, Llanuwchllyn with

Catherine’sThomas’ brother John.1The trust bond names maternal uncle Hugh and paternal uncle John, and the letters below are to John. Thomas left £329 in trust for the children.2Roughly £15K in 2020.He also left a library, consisting of one large Welsh Bible valued at £1 15s,3This is the SPCK edition of 1799, the same one that another Mari Jones received from Thomas Charles at Bala in 1800 after walking 26 miles barefoot. two small Bibles, two Testaments, one “Body of Divinity” half a dozen other religious books, one by Thomas Charles founder of Welsh Sunday Schools, a Grammar, a Dictionary and twelve magazines.

Among the Wergloddu papers are two accounts dated 1820 from a Chester School.4“Receipt for Board & Schooling for Miss Grace Jones, Mr John Parry, Chester, 13 June, 1821.” There’s no academy of that name in Pigot’s Directory for Cheshire, and this is surely John Parry, the Calvinistic Methodist minister, man of letters, and editor (1775-1846). An ex-draper, he was the author of “Rhodd Mam, a little book published in 1811, which for over a century remained the primer of systematic religious instruction for Welsh Calvinistic Methodist children.” His bookshop was on Upper Bridge Street. For Grace, January 1st. to June 13th: tuition with extras £3. 17. 8½d, board 8/- per week. For Ellinor, eight weeks October term a total of £5. 10. 10½d. Boots cost them six shillings a pair, repairs six pence.

Humphrey was apprenticed to a woollen draper in Bala for seven years but at the age of twenty was released from his apprenticeship on payment of £30.

Later he says his apprenticeship cost him £100 which presumably included board. In 1824 he went to Liverpool and was soon joined by Ellinor who stayed with cousins at first. The Welsh Chapel took them under her wings like a motherly hen.5I’m not sure whether this is a reference to whatever building preceded the Welsh Cathedral in Toxteth, or a metonym for the Calvinistic Methodist community in Liverpool.

APPRENTICE

On March 14th he wrote (in Welsh):Dear Uncle, here is Ellin as I wished but with no money. I lent her £2 but had only £2.10.0 in my possession. She heard of a situation to go to some very great gentry but she couldn’t speak English well enough …. a plan to apprentice her to a dressmaker and milliner, a Quaker, a highly respected person who promises to be a mother to her but she will have to give £24 and have food and drink and buy clothes. She will learn English in spite of herself. There is nobody there who can speak Welsh and you know that girls can’t go without talking even if it were French.

Concerning the shop of which I spoke I think it must have been a weak time on the moon, I had a weakness in my head to talk of such a thing but I wasn’t feeling very well and had home sickness. I thought of chucking up Liverpool but things are better now. Nothing bothers me except the smallness of my wages.

April 5 to John “About Ellin she is very poorly … badly in need of money to pay for her keep and she wants clothes.” He asks for £5.

September 5. Grace now in Liverpool.

We three were together last Sunday walking after chapel three miles into the country and talking about you often and about Grandfather and Grandmother.

Grace has a good place more comfortable than Ellin: Very heavy work she has to do, there isn’t much pleasure where there are nine or ten children. The steam-packet Chester burst on Sunday and many were scalded. A great many dogs killed here every day for fear they may have rabies.

February 14 1825. He writes from London to Ellin who is at home ill:

…fortunate you are with my uncle instead of being a Slave among these English devils, swearing and cursing and never go to church or chapel nor ever think of God Almighty. Better potatoes and milk in Llanuwchillyn than roast beef and wine in London. I am in a good place with Mrs. Edwards, family prayers evening and morning … keep your heart up, dear little Ellin.

April 3. From Grace, Liverpool to John, “Why doesn’t Ellin write.” Asks for £3. “Everything is frightful.”

April 6. From Humphrey. “Dear Uncle, Here I am out of a place without one halfpenny in my pocket and my old master gives me every name except thief.”

THRILLED

May 13: He writes from London to Grace at Bala for a lock of Ellin’s hair. He warns her against marrying someone “not respectable and penniless”:Last Sunday I saw Ellin’s old sweetheart, he looked very serious when he saw me. Dear Grace take care of yourself, do not listen to chaps who are like I was myself, silly and making fools of girls like you.

He begs Grace not to go back to Liverpool. “Come here dear sister, I like this place better every day.” He is thrilled by the preaching of John Elias, the most famous of Welsh preachers.

September 2. John to Grace. “Humphrey has left his place and is in great need of money. I sent him £10.”

After which the volatile twenty-one year old fades from view till his death in 1845.

Whether or not a Welsh chapel awaited Simon’s sons, Edward and Simon, in Sheffield mattered little, for they were strong and self-reliant.

Simon returned to Bala and married Grace in 1835. He took part in Radical politics and in the teetotal movement which had begun in 1832, perhaps as a reaction against forty three quarts of ale at a funeral. He was said to be the best speaker in North Wales.

The 1832 epidemic was generally held to be a Divine Visitation for sin, and as there was plenty of sin about, what with the Reform Bill and people not wanting to keep in their proper station, this seems very likely.

FOOTSTEPS

Efail y Lôn (The forge at the Lane), from Gwaith Ap Vychan (1903) by O.M. Edwards, who seems to think this was Old Simon Jones’ smithy.Simon and Mary [Jones of Lôn] survived all the children except Grace and Simon. Their daughter Mary died in 1846, Edward, at Sheffield, in the same year, Thomas in Utica in 1847.

These were years of the great potato famine, when the starving Irish millions fled across the seas.

With them went their travelling companion Typhus, so that death followed them into the overcrowded ships, and into the ports and cities of America and Britain, seeming to echo Petrarch’s lines:

Life flies and will not stay an hour

And Death with hurrying footsteps follows fast.6Francesco Petrarca’s marvellous sonnet tells of his hopeless love for Laura, now dead, and of his fear of dying himself, and having to stand before God:

La vita fugge, et non s’arresta una hora,

et la morte vien dietro a gran giornate,

et le cose presenti et le passate

mi dànno guerra, et le future anchora;

e ’l rimembrare et l’aspettar m’accora,

or quinci or quindi, sí che ’n veritate,

se non ch’i’ ò di me stesso pietate,

i’ sarei già di questi penser’ fòra.

Tornami avanti, s’alcun dolce mai

ebbe ’l cor tristo; et poi da l’altra parte

veggio al mio navigar turbati i vènti;

veggio fortuna in porto, et stanco omai

il mio nocchier, et rotte arbore et sarte,

e i lumi bei che mirar soglio, spenti.

Since this blog is nominally about mechanical musical instruments, here’s Katyna Ranieri in more prosaic mode in “La pianola stonata”, “the out of tune pianola”, which I used to sing in Barcelona:

Vecchia pianola d’un tempo,

d’un tempo passato,

tu mi ricordi il bel tempo,

il bel tempo che fu.

They came to Cardiff, Liverpool, London. Utica was one of the places to which they went from New York (Woodham Smith, “The Great Hunger”) and carried with them typhus, dysentery, even cholera.

Could Thomas have been caught up in this exodus or had he gone before? Others besides the Irish went to America. There was famine in Europe, food scarcity and a great financial crisis in Britain. Others, besides the Irish, went to America. In either case, with the Irish crammed into the hovels of Utica, it must have been a Death town, and so with many British towns.

Grace lived until 1870 and Simon until 1873. Did they, looking down from the Elysian Fields, in 1917, see their grandson [Arthur Tryweryn ApSimon] mortally wounded, dying with the Welsh at Pilchem Ridge?

Religion played a great part in the lives of these people, comforting them with glimpses of a world elsewhere. Halevy had described the early Welsh preachers as illiterate enthusiasts.

By 1860 there was a Theological College at Bala where the philosophy of Hegel buttressed the Faith, giving the students evangelical, teetotal and Hegelian, an edge on classically educated Anglican divines, who still stuck to Pusey, port and Plato.7The alliteration is fine, but the theologian Henry Liddon recalled that his proto-Anglo-Catholic colleague Pusey liked Plato but not port:

In those days French wines, now so common, were considered a great luxury. It was proposed to have French wines at table, besides port and sherry. Pusey and I agreed to oppose the plan; and we carried our point in a Fellow’s meeting. But the Provost, Copleston, forthwith said that he should give French wines on his own account. On which Pusey said to me that Oxford seemed incapable of being reformed.

Does it really end here?

Anecnotes

- 1The trust bond names maternal uncle Hugh and paternal uncle John, and the letters below are to John.

- 2Roughly £15K in 2020.

- 3This is the SPCK edition of 1799, the same one that another Mari Jones received from Thomas Charles at Bala in 1800 after walking 26 miles barefoot.

- 4“Receipt for Board & Schooling for Miss Grace Jones, Mr John Parry, Chester, 13 June, 1821.” There’s no academy of that name in Pigot’s Directory for Cheshire, and this is surely John Parry, the Calvinistic Methodist minister, man of letters, and editor (1775-1846). An ex-draper, he was the author of “Rhodd Mam, a little book published in 1811, which for over a century remained the primer of systematic religious instruction for Welsh Calvinistic Methodist children.” His bookshop was on Upper Bridge Street.

- 5I’m not sure whether this is a reference to whatever building preceded the Welsh Cathedral in Toxteth, or a metonym for the Calvinistic Methodist community in Liverpool.

- 6Francesco Petrarca’s marvellous sonnet tells of his hopeless love for Laura, now dead, and of his fear of dying himself, and having to stand before God:

La vita fugge, et non s’arresta una hora,

et la morte vien dietro a gran giornate,

et le cose presenti et le passate

mi dànno guerra, et le future anchora;

e ’l rimembrare et l’aspettar m’accora,

or quinci or quindi, sí che ’n veritate,

se non ch’i’ ò di me stesso pietate,

i’ sarei già di questi penser’ fòra.

Tornami avanti, s’alcun dolce mai

ebbe ’l cor tristo; et poi da l’altra parte

veggio al mio navigar turbati i vènti;

veggio fortuna in porto, et stanco omai

il mio nocchier, et rotte arbore et sarte,

e i lumi bei che mirar soglio, spenti.

Since this blog is nominally about mechanical musical instruments, here’s Katyna Ranieri in more prosaic mode in “La pianola stonata”, “the out of tune pianola”, which I used to sing in Barcelona:

Vecchia pianola d’un tempo,

d’un tempo passato,

tu mi ricordi il bel tempo,

il bel tempo che fu. - 7The alliteration is fine, but the theologian Henry Liddon recalled that his proto-Anglo-Catholic colleague Pusey liked Plato but not port:

In those days French wines, now so common, were considered a great luxury. It was proposed to have French wines at table, besides port and sherry. Pusey and I agreed to oppose the plan; and we carried our point in a Fellow’s meeting. But the Provost, Copleston, forthwith said that he should give French wines on his own account. On which Pusey said to me that Oxford seemed incapable of being reformed.

Does it really end here?

Similar posts

Back soon

Comments